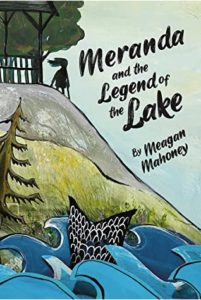

Meranda is an 11 year-old girl whose parents moved away from their Nova Scotia home and close-knit family to live in Calgary when she was only 3. While she has regular video visits with her dearly loved relatives back in Cape Breton, her helicopter parents have always been cagey about returning, until the death of her mother’s beloved Uncle Mark sends them all home for his funeral.

Meranda has long been fascinated with her hometown, whose main claim to fame is its relationship with the mermaids who allegedly live in the surrounding waters. But her mother Beth is extremely nervous about her getting too close to the lake, and perhaps not just because Meranda uses crutches to get around, a result of the cerebral palsy that makes her legs difficult to rely on. Meranda’s also painfully near-sighted, using thick glasses to help her see; between that and the fact that her coloring is completely different from her parents, she can’t help but suspect that she has closer ties to a mermaid heritage than her parents are willing to let on.

Meranda has long been fascinated with her hometown, whose main claim to fame is its relationship with the mermaids who allegedly live in the surrounding waters. But her mother Beth is extremely nervous about her getting too close to the lake, and perhaps not just because Meranda uses crutches to get around, a result of the cerebral palsy that makes her legs difficult to rely on. Meranda’s also painfully near-sighted, using thick glasses to help her see; between that and the fact that her coloring is completely different from her parents, she can’t help but suspect that she has closer ties to a mermaid heritage than her parents are willing to let on.

Unfortunately, this is only one of the many things her parents don’t care to discuss with her, and so Meranda spends the days leading up to Granduncle Mark’s funeral feeling increasingly confused by the weird reactions, if not downright hostility, of some of the townsfolk to their return. Fortunately, she makes a friend, Claire, who’s willing to help her get to the bottom of things, with perhaps the foremost issue being the mystery of what actually happened to Granduncle Mark. Did he really fall overboard from his ship or was he pulled into the waters and drowned by the lake’s increasingly combative merfolk, as some are claiming? It’ll be up to Meranda to figure out what’s going on, in the process helping her family’s small town find peace with its own mythic legacy.