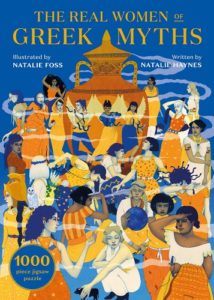

As a game designer and enthusiast myself, it’s perhaps a natural evolution of my career in book criticism to consider and cover all the many things a bookstore can provide, games included. So when I was offered the chance to review The Real Women Of Greek Myths: A 1,000 Piece Jigsaw Puzzle Based on Feminist Tales, I absolutely leapt at the opportunity.

With countless others around the globe, my interest in jigsaw puzzles was reignited by the pandemic that kept so many of us indoors for the better part of two years. My best friend even got me a mat kit with little snap-together trays one Christmas, not only to sort out pieces while working on the puzzle, but also to keep the whole caboodle clear from my little children’s naughty fingers. My puzzling tastes are fairly orthodox: I prefer strong, clear images with lots of color, and appreciate both a bit of narrative and a keen wit. I do like the occasional mystery puzzle where I go in image-blind in order to find the solution to the accompanying short story, but most of all I’m a huge fan of the Magic Puzzle Co’s innovative work and gold standard craftsmanship.

With countless others around the globe, my interest in jigsaw puzzles was reignited by the pandemic that kept so many of us indoors for the better part of two years. My best friend even got me a mat kit with little snap-together trays one Christmas, not only to sort out pieces while working on the puzzle, but also to keep the whole caboodle clear from my little children’s naughty fingers. My puzzling tastes are fairly orthodox: I prefer strong, clear images with lots of color, and appreciate both a bit of narrative and a keen wit. I do like the occasional mystery puzzle where I go in image-blind in order to find the solution to the accompanying short story, but most of all I’m a huge fan of the Magic Puzzle Co’s innovative work and gold standard craftsmanship.

So how does this jigsaw puzzle hold up in comparison? By now, regular readers will know that I’ve been obsessed with Greek mythology since I was a child. Despite this, I’d never done a Greek mythology-themed jigsaw puzzle before TRWoGM. This was a surprisingly great way to combine the two interests, as constructing the images of the women — who are delightfully shown in a full range of skin colors and body types — really helps reinforce each of their stories. I don’t think I’ve ever thought “poor Europa!” as many times as when I was putting the pieces of her together, as she crouches in the forefront of the picture, holding a toy-sized bull.