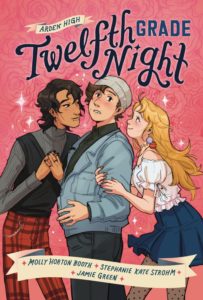

Shakespeare and I have a love-hate relationship, but I’ve always had a soft spot for Twelfth Night due to its hapless heroine Viola. I’ve even seen the play presented once professionally, in Malaysia. The production was pretty great, and the story overall less ridiculous than some others of the Bard’s (not that that’s saying much, tbqhwy.)

But how well does the 17th century play do when transplanted to the 21st century? Really well in some parts, tho any flaws in this graphic novel adaptation, set in a modern-day high school (with very neat paranormal elements!), I lay squarely at the feet of Shakespeare himself.

But how well does the 17th century play do when transplanted to the 21st century? Really well in some parts, tho any flaws in this graphic novel adaptation, set in a modern-day high school (with very neat paranormal elements!), I lay squarely at the feet of Shakespeare himself.

We start with new girl Viola Messina, who’s thrilled to get away from her old private boarding school so she can dress the way she likes at the local public school, Arden High. She thought her twin brother Sebastian was going to come with her, but at the last minute he decides to stay at St Anne’s, leaving her feeling lonely and friendless as she walks into her new school. Fortunately, Tanya, Queen of the Fairies and leader of Arden High’s social committee, is on hand to help show her around.

Vi literally bumps into hot poet and influencer Orsino in the cafeteria, and the two strike up a friendship. As Vi develops a crush on him, she doesn’t realize that he thinks she’s a lesbian. Thus, he thinks it’s totally fine to ask her to ask her new friend Olivia if Olivia will go to the dance with him. But Olivia — who also thinks Vi is into girls — has a crush on Vi. Shenanigans ensue.