Not quite 30 years ago I was backpacking around southeastern Europe when something unfortunate happened: I ran out of books. Well, technically, I did not run out of books; my backpack still held what a reasonable person would probably consider more than enough books. But since I had last replenished from the freebies at a youth hostel on Rhodes, I had read all of the ones I had with me, and some of the freebies were too dreadful to consider re-reading. A couple of weeks — how long they seemed! — later when I found an international bookstore in Heraklion, I did the obvious thing and stocked up. Not in number of books, mind, but in pages and heft. I bought two books. The first was Der Zauberberg (The Magic Mountain) by Thomas Mann, which I actually started to read. I made it to page 516, and there’s still a 100-drachma note that marks the extent of my progress. The second was a Penguin Classics edition of The Brothers Karamazov. I may have read the introduction, I certainly didn’t get to the main text. Yet these two served their purpose. I never felt unbooked again on that trip, which ended with me finding a job in Budapest.

The year 2021 marked the bicentennial of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s birth, and for the occasion Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky revisited their translation of The Brothers Karamazov, “go[ing] over every word of our original version, catching occasional errors or misreadings, rethinking word choices, altering certain rhythms and phrasings.” (p. xi) Back in September, I attended a no-particular-book book club, and it was great! One of the participants mentioned that she was reading Karamazov. I had a copy of the bicentennial edition waiting on my shelves. And so, two months and 823 pages later, give or take some Notes and a not overly long Introduction, here I am.

I took two main ideas away from the Introduction. The second is that the “author” of The Brothers Karamazov is a character within the story, and he is not Dostoevsky. That is, he is something of a throwback to the Enlightenment narrators who addressed the reader directly, and he situates himself within the town where Karamazov takes place. He mentions gathering reports to tell the story, and he says he was present at the trial that closes the main part of the story. He does not detail how he knows of conversations or mental states; the reader is meant to take the “author’s” near-omniscience on faith. Dostoevsky is nothing if not inconsistent, though. As Pevear writes, “There are stretches when the person of the ‘author’ seems to recede and be replaced by a more conventional omniscient narrator, but his voice will suddenly re-emerge in a phrase or half-phrase, giving an unexpected double tone or double point of view to the passage.” (p. xviii)

The first thing I took from the Introduction comes from its opening sentence: “The Brothers Karamazov is a joyful book.” (p. xiii) Pevear continues:

Readers who know what it is “about” may find this an intolerably whimsical statement. It does have moments of joy, but they are only moments; the rest is greed, lust, squalor, unredeemed suffering, and a sometimes terrifying darkness. But the book is joyful in another sense: in its energy and curiosity, in its formal inventiveness, in the mastery of its writing. And therefore, finally, in its vision. (p. xiii)

Continue reading

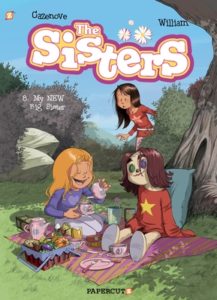

Wendy is the older sibling, a dark-haired teenager with the physical benefits of strength, size and speed. She has two best friends who are deeply concerned by the escalation of hostilities, and a boyfriend, Mason, who is as often the target of Maureen’s pranks as he is her co-conspirator, unwitting or otherwise.

Wendy is the older sibling, a dark-haired teenager with the physical benefits of strength, size and speed. She has two best friends who are deeply concerned by the escalation of hostilities, and a boyfriend, Mason, who is as often the target of Maureen’s pranks as he is her co-conspirator, unwitting or otherwise.