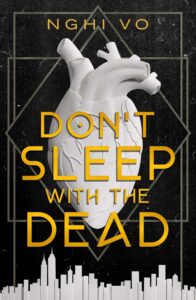

I didn’t super love the book for which this novella is a sequel. The Chosen And The Beautiful was Nghi Vo’s somewhat uneven, I felt, retelling of The Great Gatsby. But I do enjoy Ms Vo’s writing, as well as the novella form, so was happy to dive in here.

Don’t Sleep With The Dead is set in New York City some twenty years after the disastrous events of TCatB, as 1939 fades into 1940. Jordan Baker has moved to Paris, where the phantoms of dead soldiers march through the streets. Our viewpoint character here instead is Nick Carraway, who’s recently published a book that sounds a whole lot like F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

Don’t Sleep With The Dead is set in New York City some twenty years after the disastrous events of TCatB, as 1939 fades into 1940. Jordan Baker has moved to Paris, where the phantoms of dead soldiers march through the streets. Our viewpoint character here instead is Nick Carraway, who’s recently published a book that sounds a whole lot like F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

As DSwtD begins, Nick is caught up in a raid on gay men cruising in Prospect Park. He manages to escape with the intervention of someone he can barely believe is alive again: Jay Gatsby himself. But was Nick mistaken? Was his desire to see Gatsby again the reason for this unexpected manifestation?

Unable to let go of the idea of Gatsby somehow being alive, he begins to wander the city, in search of answers and, perhaps, solutions. Along the way, he leads readers on a mystical tour of the strange reality he lives in, powered by magic and demons, punctuated by occasional phone calls with Jordan, who saved him once but can only do so much over distance and time. But the shade of Gatsby lingers over everything. What will Nick do — and what will he sacrifice — to either find Gatsby or lay his spirit to rest for good?