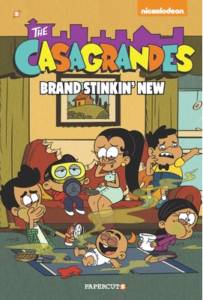

Another charming installment of the comic book series adapted from the Nickelodeon cartoon The Casagrandes. Volume 3: Brand Stinkin’ New has the added bonus of being entirely comprised of vignettes written especially for this book!

While that does mean fewer Loud family shenanigans from, particularly, Lincoln and Lori making cameo appearances here, this does give the Casagrandes and their friends in the city more time to shine. I greatly enjoyed how most of the stories here were loosely tied to the idea of something new. A particular favorite was the one where Ronnie Anne Casagrande and her upstairs neighbor and best friend Sidney Chang experimented with making fusion food, combining Mexican and Chinese delicacies for some truly scrumptious new dishes… and some perhaps a little less than appetizing. I also really enjoyed the denouement of the story where Carlota Casagrande was trying to persuade her overly sentimental mother Frida to participate in a closet purge, and how that birthed something wonderful and different.

While that does mean fewer Loud family shenanigans from, particularly, Lincoln and Lori making cameo appearances here, this does give the Casagrandes and their friends in the city more time to shine. I greatly enjoyed how most of the stories here were loosely tied to the idea of something new. A particular favorite was the one where Ronnie Anne Casagrande and her upstairs neighbor and best friend Sidney Chang experimented with making fusion food, combining Mexican and Chinese delicacies for some truly scrumptious new dishes… and some perhaps a little less than appetizing. I also really enjoyed the denouement of the story where Carlota Casagrande was trying to persuade her overly sentimental mother Frida to participate in a closet purge, and how that birthed something wonderful and different.

Frida also provides a very relatable Mom punchline for the story “Blanket Statement”. I really like watching style-conscious Carl have more room to grow in these pages, too, as I felt like he got shorter shrift in previous books. And, as always, it’s wonderful to see CJ, who has Down’s Syndrome, star in his own stories. The representation in these books is always terrific and this volume was no different.