The best time to enjoy tales of pirates is when you’re a kid, when it’s all about the romance of the high seas, with no thought as to the terror, rapine and death left in the wake of these often exceedingly violent criminals. I mean, who doesn’t dream of sailing away from their troubles, swaggering through life free as a bird? I absolutely understand the appeal, even as I find adults who’re seriously into this lawless pirate stuff to be a little, if you’ll excuse the pun, unmoored from reality.

But kids should absolutely dream of exploring the world care-free, as our protagonist Pirate Pearl does in the company of her “rainbow chicken” Petunia. Pearl is actually in the middle of a voyage when she’s beset by that greatest enemy of all travelers: hunger. Hardtack just won’t cut it any more, so she and Petunia drop anchor and head ashore on an epic quest for food. Just as she’s about to expire from hunger, she’s rescued by the kindly Farmer Fay, who not only resuscitates her with some potato soup but also introduces her to the miracle that is my favorite vegetable. Best of all, Fay shows Pearl how to grow potatoes herself, whether on a farm like Fay’s or aboard a pirate ship like Pearl’s.

But kids should absolutely dream of exploring the world care-free, as our protagonist Pirate Pearl does in the company of her “rainbow chicken” Petunia. Pearl is actually in the middle of a voyage when she’s beset by that greatest enemy of all travelers: hunger. Hardtack just won’t cut it any more, so she and Petunia drop anchor and head ashore on an epic quest for food. Just as she’s about to expire from hunger, she’s rescued by the kindly Farmer Fay, who not only resuscitates her with some potato soup but also introduces her to the miracle that is my favorite vegetable. Best of all, Fay shows Pearl how to grow potatoes herself, whether on a farm like Fay’s or aboard a pirate ship like Pearl’s.

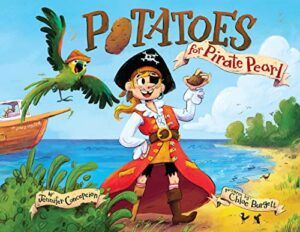

This seems like a simple enough story but Jennifer Concepcion and Chloe Burgett have teamed up to create something entirely magical, with help from their publisher’s sponsoring body, the American Farm Bureau Foundation For Agriculture. Pearl is an utterly charming main character who is fully committed to the (pirate) bit in the way of all imaginative children. Fay is her good-natured mentor who is happy to play along but also knows when to guide Pearl’s piratical ways back to the strait (lol, I’m sorry, I love pirate jokes and puns) and narrow.