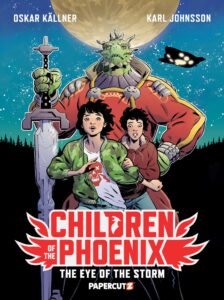

I somehow managed to persuade my 13 year-old to read this with me, and we were both incredibly delighted by this sweet, spunky tale of a young girl living in the middle of nowhere who discovers that magic really does exist in her life.

Ten year-old tomboy Avery helps her father run a gas station in the middle of a practically deserted desert valley. She has no friends because there are so few other people around, and none of them are her own age. When she’s not helping customers at the pumps, her main pastime is learning magic tricks, in hopes of injecting a little excitement into her humdrum existence. Her dad tries his best — he’s funny and sweet — but there’s really only so much you can do when you’re living out in isolation.

Ten year-old tomboy Avery helps her father run a gas station in the middle of a practically deserted desert valley. She has no friends because there are so few other people around, and none of them are her own age. When she’s not helping customers at the pumps, her main pastime is learning magic tricks, in hopes of injecting a little excitement into her humdrum existence. Her dad tries his best — he’s funny and sweet — but there’s really only so much you can do when you’re living out in isolation.

When Dad drives into town one day, leaving Avery in charge, she finds herself in need of a new lightbulb. Hoping to find one in his cluttered garage, she unearths instead an old-timey lantern. As she dusts it off, a brilliant blaze erupts from it, along with an adorable little monkey-cat hybrid named Gribblet (whom Jms and I immediately cooed over like he was a Pokemon.) Once Gribblet realizes who she is, he helps her embark on a journey that will not only show her that magic is real but that she herself is far more magical than she ever imagined.