OMG, that was so hard to read on digital, friends, get the physical copy! This was such a good book, but such a challenge for me to read on a screen when the text abruptly switched to white on a dark background, given my astigmatism. It was absolutely worthwhile tho!

Mary Tyler MooreHawk starts out as an all-ages futuristic sci-fi comic a la Jonny Quest, featuring the titular character as she and her family travel the universe, seeking to stop evildoers and their terrible plans for galactic dominion. Mary has a sentient robot brother named Cutie Boy, whom she loves even tho he can be annoying at times; a strained relationship with her stepmother Meredith Moorehawk-Cho, and a devoted bodyguard in the form of Roxanne “Roxy” Racer. As believers in super science, they’re committed to building better tomorrows for all people. Along the way, they’ve picked up plenty of allies but also many deadly enemies, including Dr Zebra, the arch-nemesis of Mary’s late mom, Roseanne MooreHawk. Drs MooreHawk and Zebra allegedly perished together while struggling over an Einstein-Rosen bridge… but what is death really in the face of super science?

Mary Tyler MooreHawk starts out as an all-ages futuristic sci-fi comic a la Jonny Quest, featuring the titular character as she and her family travel the universe, seeking to stop evildoers and their terrible plans for galactic dominion. Mary has a sentient robot brother named Cutie Boy, whom she loves even tho he can be annoying at times; a strained relationship with her stepmother Meredith Moorehawk-Cho, and a devoted bodyguard in the form of Roxanne “Roxy” Racer. As believers in super science, they’re committed to building better tomorrows for all people. Along the way, they’ve picked up plenty of allies but also many deadly enemies, including Dr Zebra, the arch-nemesis of Mary’s late mom, Roseanne MooreHawk. Drs MooreHawk and Zebra allegedly perished together while struggling over an Einstein-Rosen bridge… but what is death really in the face of super science?

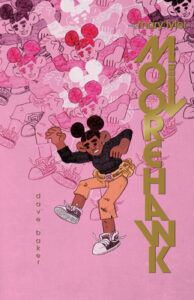

Interspersed with these comics, featuring an exhausting number of supporting cast members and done mostly in black and pinks, are curious prose and photography chapters that purport to be articles from a magazine called The Physicalist. These articles gradually build a picture of a dystopian future where corporations were granted full rights as people and the subsequent atrocities, some worse than others, committed therefrom. The story of Mary Tyler MooreHawk was made into a live-action show broadcast on dishwashers, as few people had televisions after the purges that rid most people of physical belongings, books and comics included. The show enraptured many, including the members of the Physicalist movement, who care about physical objects as being more than purportedly useless vanity.