Hahaha, omg, Linnea is a much better person than I am, I would never want to speak to Cobalt again after what happens mid-way in this book!

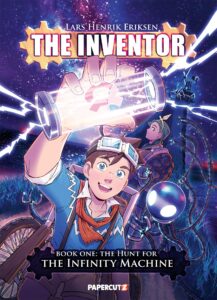

But before we get there, this graphic novel — with strong overtones of both Hayao Miyazaki and Pokemon properties — tells the tale of Cobalt Cogg, a young man who wants to grow up to be an inventor just like his grandfather. Grandpa is already viewed with some suspicion by the other inhabitants of Mata-Mata. Despite having brought electricity to the island, Grandpa Alfred is considered something of a menace. While his inventions do make life easier for the islanders, many of them are viewed with distrust, especially by Mayor Barlind, the dad of Linnea, Cobalt’s best friend. Mayor Barlind is a traditionalist through and through, and believes that the dangers of Alfred’s gizmos don’t necessarily outweigh the benefits that they bring.

But before we get there, this graphic novel — with strong overtones of both Hayao Miyazaki and Pokemon properties — tells the tale of Cobalt Cogg, a young man who wants to grow up to be an inventor just like his grandfather. Grandpa is already viewed with some suspicion by the other inhabitants of Mata-Mata. Despite having brought electricity to the island, Grandpa Alfred is considered something of a menace. While his inventions do make life easier for the islanders, many of them are viewed with distrust, especially by Mayor Barlind, the dad of Linnea, Cobalt’s best friend. Mayor Barlind is a traditionalist through and through, and believes that the dangers of Alfred’s gizmos don’t necessarily outweigh the benefits that they bring.

Cobalt and Linnea, ofc, do not share the mayor’s concerns. But a freak accident causes Alfred to be banished from the island, and the friends grow up over the next five years without his presence. When Cobalt finally assembles all the pieces he needs to follow the blueprints Alfred left behind for him, he inadvertently shorts out the power supply that has miraculously run untended for the duration of Alfred’s absence. With Linnea’s help, he finds a solution… but also a greater mystery. Is the map that Cobalt found in Alfred’s abandoned lab showing him where his grandfather is now? There’s only one way for our young inventor to find out!