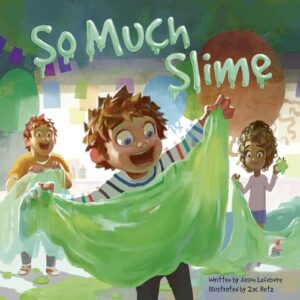

Matty is a grade-schooler who loves making homemade slime with his parents. When he gets permission to demonstrate how to make slime in art class at school, he’s super excited! He packs enough ingredients so that all his classmates can get some slime to take home with them, and repeats to himself the simple recipe his parents taught him: glue, baking soda, saline — and pizzazz!

His art teacher is at first a little perturbed by the sheer amount of slime Matty is planning on making. But Matty assures her that he knows what he’s doing… until he doesn’t. Examining the waves of sticky goop he’s unleashed in class, he realizes that he’s forgotten the saline! His classmates try to come up with creative ideas to sop up the mess that’s threatening to drown poor Matty, but their attempts to help only make the waves of slime get bigger. Will anybody be able to figure out how to fix things before it becomes an uncontrollable disaster?

His art teacher is at first a little perturbed by the sheer amount of slime Matty is planning on making. But Matty assures her that he knows what he’s doing… until he doesn’t. Examining the waves of sticky goop he’s unleashed in class, he realizes that he’s forgotten the saline! His classmates try to come up with creative ideas to sop up the mess that’s threatening to drown poor Matty, but their attempts to help only make the waves of slime get bigger. Will anybody be able to figure out how to fix things before it becomes an uncontrollable disaster?

This was an absolutely adorable picture book about making that toy? material? that so many kids (and their parents!) adore. Personally, I like slime for how it helps clean irregularly shaped items, but that’s neither here nor there. The enthusiasm of Matty and his parents is infectious, and even tho the demonstration goes a lot more haywire than planned, all’s well that ends well. Matty and his art teacher might be a little traumatized by the experience, but it’s clear that all the other kids had a blast as they tried to help solve the problem. Plus, the coda reinforces the fact that while not all experiments (or demonstrations) are successful, making notes of both what worked and what went wrong are valuable, scientific learning experiences.