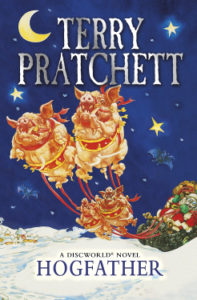

Twenty books into Discworld, Terry Pratchett has set up enough pieces of furniture in the various fictional rooms on the Disc that moving just a few of them around is bound to produce something interesting. In Hogfather, he has Death, Death’s granddaughter Susan, a member of the Assassins’ Guild who’s too good at what he does and enjoys it too much, and some of the senior faculty of the Unseen University. Pratchett also tries out one of the classical unities, setting the novel’s action almost entirely in one night, although some of the characters’ abilities mean that time does not behave in a strictly linear fashion when they are around. The particular night is the longest one of the year, when according to Disc tradition, the Hogfather speeds around on his sleigh (drawn by flying pigs) distributing gifts to children.

Only this year, something seems to have gone seriously wrong, and the Hogfather is nowhere to be found. His usual stand-ins are there for the commercial frenzy leading up to the holiday, but the jolly man in the red suit is not where he is supposed to be. That is the first sign that all is not well in the lattice of superstition and belief that supports much of the doings on the Disc. Death steps in to fill part of the gap, but he has to learn the role as he goes.

At a department store, a child has just agreed to be good in exchange for a toy castle, a play army

—and a sword. It was four feet long and glinted along the blade.

The mother took a deep breath.

“You can’t give her that!” she screamed. “It’s not safe!”

IT’S A SWORD, said the Hogfather. THEY’RE NOT MEANT TO BE SAFE.

“She’s a child!” shouted Crumley.

IT’S EDUCATIONAL.

“What if she cuts herself?”

THAT WILL BE AN IMPORTANT LESSON.

Uncle Heavy whispered urgently.

REALLY? OH, WELL, IT’S NOT FOR ME TO ARGUE, I SUPPOSE.

The blade went wooden. (pp. 142—43)