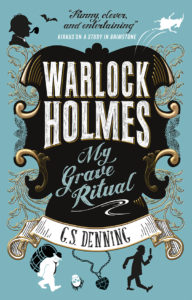

Q: Every series has its own story about how it came to be conceived and written as it did. Reading A Study In Brimstone, I figured this series would mostly be a light-hearted spoof, so have been greatly excited by how it has developed into an intriguing, complex ongoing narrative with the release of My Grave Ritual. How did the Warlock Holmes books evolve in your mind and on the page?

Q: Every series has its own story about how it came to be conceived and written as it did. Reading A Study In Brimstone, I figured this series would mostly be a light-hearted spoof, so have been greatly excited by how it has developed into an intriguing, complex ongoing narrative with the release of My Grave Ritual. How did the Warlock Holmes books evolve in your mind and on the page?

A: You know, I thought it would be a simple spoof, too, for a minute. The day I started, I sat down to write a short story, just for yucks. But that night, as I lay in bed thinking about it, I realized I didn’t want to. I’d started to like the idea too much. I realized it could hold a series and—judging by the history of geek-love for Sherlock—I figured I could get it published. So I dove right in.

Q: Do you write with any particular audience in mind? Are there any particular audiences you hope will connect with this story?

A: I think the audience is… me. And all the people out there who are basically me. The Whovians. The Sherlockians. The lovers of Adams and Pratchett. The people who should probably stop giggling at fun geek stuff and get a real job, but who resist with every fiber of their soul. Hi guys! Here’s a book for you.

Q: What is the first book you read that made you think, “I have got to write something like this someday!”

A: I think it was The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. I already loved sci-fi/fantasy. And I already loved humor. To see them married like that made me so happy! But there wasn’t enough, you know? I’ve been churning out geek humor for over two decades, but mostly on the stage, not on the page.

Q: Your author biography states that you did over two decades of improv before finally learning to write stuff down. How did your experience with improv inform your writing process?

A: Improv taught me to write. It taught me what an audience likes and how to feel when my story was on the ball and when it wasn’t. If you want to write, I highly recommend trying improv. Oh, as a special bonus: anybody who has to make up 8 stories per night while a live audience watches is not going to suffer from writers’ block.

Q: Do you adhere to any particular writing regimen?

A: Someday, I’d love a writing regimen. Sigh… Someday… Right now I’m still working 40 hours a week doing MRI and trying to keep my two young kids happy and alive. The books you’ve been reading were written a few hours at a time at coffee houses or burger joints that will let me sit in a corner table and write. I steal time after the kids are asleep or between dropping them off at school and heading in to work. I swear 50% of book 3 was written at Red Robin on Friday nights after work.

Q: While reading A Study In Brimstone, I was certain you were a pantser (someone who writes by the seat of their pants) but by the end of My Grave Ritual, I’m convinced you must be a plotter. Which do you think you tend to be?

A: Well, you were never wrong. I’m a bit of both. I tend to figure out the large plot/thematic points I want to hit and write towards them. Oh, and I have help on this particular project. A famous British dead guy wrote all my plot outlines for me a hundred years ago. Any of you pansters out there who want to try writing to an outline, but don’t know how to make a solid plan, try this: write a parody. Strip the muscles and skin off a beloved old story. Keep those solid and venerable bones, but give it new flesh. It’ll teach you a lot.

Q: Given your broad background in geekdom, what made you choose Sherlock Holmes pastiche specifically as your means of expression?

A: It was an accident. I had just watched the first episode of the BBC’s Sherlock and found myself recommending to a fantasy writer that she build a powerful-but-flawed character like Holmes for her book. She said Holmes would never work in fantasy—how would you ever adapt that. On the drive home, I started laughing, because the answer occurred to me and it was so simple: everybody thought he was magical, anyway, so all you had to do was let him be. Then I thought up the pun Warlock Holmes. I was so excited. I ran upstairs to Google it and see what the geeks before me had done with that joke. There was nothing. So I sat down to write it myself.

Q: What has been the reaction of Sherlock Holmes fans to your novels?

A: Surprisingly good. I thought I was going to get flamed so hard. I am, after all, messing with one of the most beloved literary figures of all time. But I’m doing it lovingly enough, I think, and with enough nods and Easter-eggs to the originals that the Holmes fanbase has been exceedingly welcoming to me. There was one guy who gave me a one star review and called the series “Openly-flaunted degeneracy.” That was so choice, we were going to use it as the top blurb on the back of book 3, but he took it down. Boooooo!

Q: Readers can expect the fourth and fifth books in the series, The Sign of Nine and The Finality Problem, in April of 2019 and 2020 respectively. What can you tell us about your next project, whether it be these upcoming books or something else entirely?

A: Let’s see… Book 4 is all about Watson’s darkest days. He’s trying to figure out how magic and Moriarty and Adler work and he’s injecting himself with a mystic solutionn to have prophetic dreams. It’s slowly killing him, but he can’t stop trying to get that last clue he needs to best Adler. Book 5 is all about Watson’s adventures in matrimony with Mary Morstan. I also have a YA novel done and ready to market if my agent ever decides to give it a spin (you listening, Sam?) It’s basically Romeo and Juliet if the Montagues were the Indiana Joneses and the Capulets were mad scientists.

Q: What are you reading at the moment?

A: My own stuff, over and over? The original Holmes stories, over and over? Oh! Actually I’m re-reading Scott Lynch’s Lies of Locke Lamora. Really satisfying fantasy con/heist story. Highly recommended.

Q: Are there any new books or authors that have you excited?

A: What I’m really excited about now is actually a literary trend I’m hoping will take off. I am able to do my books because Sherlock Holmes is moving into the public domain. The other one that is going in right now is the collected works of H.P. Lovecraft. I can’t wait to see what people do. Who’s got a humorous Lovecraftian series? I want to read it!

Q: As a self-proclaimed “terribly friendly geek”, what is your favorite geeky pastime and why?

A: Pen-and-paper role playing, especially with authors and improvisors. If you play kick-in-the-door-kill-the-monster-take-its-treasure-style, live RPGs are just crappy seconds to video-game RPGs. But, when the stars align, when you get the right group and a narrative-based adventure, you get to be a character in your favorite story, ever.

Q: Tell us why you love Warlock Holmes!

A: The size of it. There are so many original stories, so many beloved characters, so many mysteries and plots that I really get to take my time and let Warlock grow and expand at the pace I want. I’ve got a nested plot structure. Each mystery has its own plot. Each book has an overarching plot (Book 1 is the intro. Book 2 is Holmes’s origin and Watson coming into his own as an adventurer. Book 3 is the villains coming in to mess the boys up. Book 4 is the descent into darkness). And the series itself is the story of how Holmes and Watson broke the world. The sheer size of the original canon and the geek-world’s collective patience with my series means I get to let it grow and change.

Thanks for taking an interest in Warlock, Watson and me. As long as you guys keep reading ‘em, I’ll keep writing ‘em!

~~~

Author Links:

g s denning

~~~

My Grave Ritual was published May 15th 2018 and is available via all good book sellers. My review of the book itself may be found here.