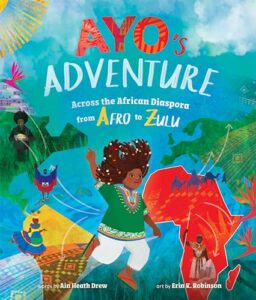

Happy October, readers! With Black History Month starting in the UK, what better time to explore a book on Africa and its diaspora?

Ayo is a young boy in America whose parents are doing a wonderful job teaching him about his heritage. While he’s proud to be a Black American with a rich generational history in the United States, he’s also tapped into the positive influences of Africa and its impact worldwide. As he’s falling asleep one night, his drowsy brain takes him on an A to Z journey through some of the major historical highlights and cultural contributions of the African diaspora worldwide.

Ayo is a young boy in America whose parents are doing a wonderful job teaching him about his heritage. While he’s proud to be a Black American with a rich generational history in the United States, he’s also tapped into the positive influences of Africa and its impact worldwide. As he’s falling asleep one night, his drowsy brain takes him on an A to Z journey through some of the major historical highlights and cultural contributions of the African diaspora worldwide.

A begins with Afro, before bouncing to Braids, hair issues that, while nominally linked to the USA in the book, are a concern for every Black person who’s ever been made to feel less than respectable for having natural hair. The book then swings down to Trinidad & Tobago to celebrate Calypso music before heading to Mali to explore Dogon culture, and from then on to the rest of the world.

Well, not the entire rest of the world: there’s precious little in Europe or Asia. While the African diaspora in Asia only gained a significant toehold in the 21st century, it does seem a little odd from a truly global perspective that no mention of their impact in Europe is made here. But that’s fine: this is a picture book from the United States, after all, and it covers so much elsewhere, especially on under-reported places in South America!