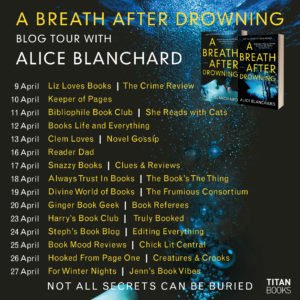

Kate Wolf is a psychiatrist specializing in at-risk adolescents. She has a great boyfriend whom she loves almost as much as she loves her job, but her family history has made it so she has massive intimacy issues. Her father is a family physician and someone she’s always striven to emulate, but their relationship is fraught due to his emotional coldness, which has grown more and more frigid since the twin tragedies of losing her mother first to suicide then her younger sister six years later to the murderer next door. As the execution date of Henry Blackwood draws closer, Kate is more than ready to leave with her boyfriend on a media-free vacation. Unfortunately, a tragedy at work keeps her in Boston, where she’s approached by a former cop who is unconvinced of Blackwood’s guilt. As Kate begins to realize that the real killer might still be out there, she also starts to worry that she’s losing her grip on reality, as family secrets and a madness that refuses to be sated threaten to take over her life and destroy it.

A Breath After Drowning explores trust issues on several levels, before neatly severing, or at least casting severe doubt on, the reader’s belief in each of the people Kate relies on through the course of this book. It’s an unsettling experience, losing all your narrative moorings, and one of the best evocations of paranoia I’ve experienced in a long time. I trusted no one, strongly suspecting all the characters that Alice Blanchard built for us, and really enjoyed the weird emotional parallel I felt to poor Kate lost in a snowstorm about three quarters of the way through. And still I was surprised by the revelation of the actual killer!

Usually with thrillers, the ending after the climactic reveal feels like a bit of a let-down, with damaged souls trying to fumble their way back to normalcy. But I was genuinely heartened by the ending of ABAD, with its promise of health and wellness in every respect. A very satisfying thriller from a writer who knows how to work the reader’s emotions.

The Frumious Consortium is participating in our very first book tour with the publication of ABAD and will be featuring an interview with Ms Blanchard next week! If you’re interested in reading more, check out the other blogs on the tour, and come back in nine days to hear more from the author herself!

the book before realizing that I’m not as decrepit as I thought, and ooh yeah, Yoon Ha Lee knows how to throw his narrative punches!

the book before realizing that I’m not as decrepit as I thought, and ooh yeah, Yoon Ha Lee knows how to throw his narrative punches!