Q. Every book has its own story about how it came to be conceived and written as it did. How did After The Eclipse evolve?

Q. Every book has its own story about how it came to be conceived and written as it did. How did After The Eclipse evolve?

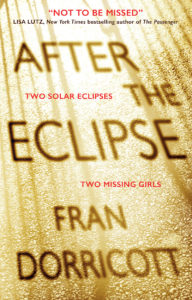

A. I first had the idea for After the Eclipse during the 2015 solar eclipse. It started off as a flash of inspiration – what if something bad happened right now? In the darkness, how soon would people realise? I love the intricasies of stories/novels where bad things happen because people are distracted. It can leave a person with a lot of guilt, even if it was an accident. So I started to think about what might happen in that situation, say, if the one ‘at fault’ was only a child herself. Old enough to know better but still young enough to be distractable.

The idea grew from there, really. I was drawn to Olive’s character, to ideas that solar eclipses have been regarded as unlucky or as bad omens. I always wanted to set a novel in a town that was reminscent of the places I spent time growing up. It felt very organic.

Q. Do you write with any particular audience in mind? Are there any particular audiences you hope will connect with this story?

A. I knew I wanted to write a book for people like me. I love reading about the darker side of human nature. I also knew I didn’t want to write anything gratuitous, especially because the story involved children. Yet I didn’t want to forget the victim, so I knew I had to balance the Olive chapters carefully. I also like reading books about characters who seem very human; that is, they’re flawed, they make mistakes, they’re hot-headed and unstable and anxious and sometimes make very bad decisions. I think there’s sometimes a gap in genre fiction for books with narrators who are in their twenties – we’re considered ‘too old’ to read young adult (not that it stops us) and in adult books we don’t necessarily want to read about people with children because a lot of us aren’t there yet. As a narrator Cassie sits in that gap. Plus, she’s an unapologetically queer woman, whose narrative arc doesn’t centre around her coming out – and I hope that LGBTQIA+ readers can connect with her story. I for one love reading books where a character is diverse but isn’t defined by their sexuality.

Q. What is the first book you read that made you think, “I have got to write something like this someday!”

A. The first one was probably Fingersmith by Sarah Waters. I read it without any preconceptions and was absolutely blown away – both by her writing style and characterisation and by the meticulous plotting that left me with my jaw on the floor halfway through. (If you’ve read it, you’ll know what I’m talking about – and if you haven’t, you absolutely should). Although it’s not a crime novel there’s a strong element of mystery about the book and the way Waters layers the elements of the story together is stunning. I was already writing at this point, but Fingersmith was the first book I read that made me sit and wish I’d written it.

Q. How did you learn to write?

A. I’ve always written. At least for as long as I remember! But probably the most formative thing in my early writing experience was discovering National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo). It happens every year in November and authors from all over the world try to write 50,000 words in a month. I first took part when I was around 14 years old and it gave me the determination to finish a draft! The writing group I joined was so supportive and enthusiastic. Everything I learned later in creative writing classes definitely built on a foundation that a local community helped me to build as an early teen. I’ve also always read voraciously, and I know that this absolutely has something to do with the burning desire to write. If you read enough books and still don’t see yourself reflected in them enough, plus you have an overactive imagination, it’s really only a matter of time.

Q. Do you adhere to any particular writing regimen?

A. I’m really fast and loose with my writing regimen. When I’m drafting I try to write every day, and I’ll have days where I write a lot. I sort of eat, sleep and breathe whatever I’m working on, and don’t take breaks. I get kind of obsessed. Then, between drafts, I don’t write very much at all. I sit and let the story stew for a bit before going back to it. Read some books, sleep a bit… I’m a very all or nothing kind of girl.

Q. Are you a pantser (someone who writes by the seat of their pants) or a plotter? After The Eclipse is so intricately layered that I’d be very impressed if it wasn’t planned out in detail beforehand!

A. I am absolutely NOT a plotter. I wish I was! After the Eclipse was the result of me trying to plot and failing miserably and then giving up and just pantsing the whole thing. It went through a lot of revisions though, to get it where it is. I always knew whodunnit, and I always knew the emotional end of the story, but the bits in the middle were carved out in various different iterations until I got the right ones. I’m flattered that you think it’s intricately layered though! It means I’ve done my job.

Q. What made you choose mystery-writing as your means of expression?

A. I’ve always loved mysteries – I think, in some form of other, most people do. We love to ask why and how. Growing up I watched a lot of crime shows. I started on Scooby-Doo (of course!) and ended up years later on CSI, Cold Case, Criminal Minds, and Law and Order: SVU (still a firm favourite). I also think that sometimes crime novels have the ability to dissect culture in a way that other genres sometimes can’t. There’s an inherent dichotomy built into the structure and you, as an author, can explore both the good side and the bad. Motivation plays such a key role, and allows readers to see into many different kinds of thoughts. I think we need more empathy in everyday life, and I genuinely believe crime readers and writers are some of the most empathetic people I’ve ever met!

Q. I’ve read that you’re also working on dark fantasy for young adults, which seems quite different, on the face of it, from psychological thrillers for adults. What draws you specifically to these genres as the ones you prefer to write?

A. I honestly don’t think that the genres are that different on a very base level. They’re about psychology, about what scares people. They’re both about the darker sides of human nature. I’m drawn to anything that gives me insight into the depths of the human experience, darkness and obsession and even killer instinct. I think that’s what causes people to slow down when they see a car crash to have a look, it’s the kind of thing that draws people to read books and watch documentaries about serial killers. Humans are different from other species because we want to know why. Why everything is the way it is, why we do some things and not others – and why some people don’t have the same inhibitions. There’s something addictive about it, I think.

Q. Off the top of my head, I can’t think of any other crime novels that have a lesbian journalist as the heroic POV protagonist (tho I do very much have a soft spot for Stuart MacBride’s DS Roberta Steel, who finally earned her own book in recent years.) How important do you feel representation is, particularly in the fairly mainstream genre of psychological thriller?

A. I think it’s so important! There are so many people out in the world who simply don’t see themselves reflected in popular culture, and it can be really damaging – especially for people who struggle with their identities or want reassurance that they’re not alone. I’m almost certain I would have understood my own sexuality sooner had I seen it reflected in more books I read and shows I watched. It was actually a book with a lesbian protagonist that finally made me accept myself! I think we can’t underestimate the importance of diversity in fiction and the impact it will have not only on young people but on those of us who are a little older and who still want to feel loved and accepted by the world.

Q. What can you tell us about your next project?

A. I can’t tell you very much, but I can say that it’s another stand-alone psychological thriller about a serial abductor who steals children from their beds in the middle of the night and the two women who team up to unmask him. It’s another story about the darkness within humanity and the affect that past traumas can have on people.

Q. What are you reading at the moment?

A. I’m currently jumping between two books. I’m reading the second novel in Leigh Bardugo’s YA Grisha trilogy Siege and Storm, which is fabulous, and I’m also reading an advance copy of Roz Watkins’ second DI Meg Dalton book Dead Man’s Daughter. I absolutely loved The Devil’s Dice and I’m so excited to see what Meg gets up to on her second outing.

Q. Are there any new books or authors in crime fiction that have you excited?

A. Aside from Roz Watkins’ new book, I’m also looking forward to getting around to reading The Hunting Party by Lucy Foley. I’ve heard such amazing things! It’s set in a remote hunting lodge in the Scottish wilderness and is about some old friends who gather for New Year only to have one of their group die – at the hands of a friend. It sounds excellent and I love locked room mysteries!

Q. Tell us why you love your book!

A. I’m so endlessly proud of After the Eclipse and there are a whole lot of reasons why I love this novel. Cassie is unapologetically queer, it’s a novel that doesn’t forget the victim and I hope is quite touching, it has this superstitious, dark undercurrent, plus is set in a small British town with some Druid stones, and lots of spookiness! I hope some readers love it as much as I do.

Author Links

~~~

After The Eclipse was published in the US on March 5th 2019 and may be found at all good booksellers. My review of the book itself may be found here.