Q. Every book has its own story about how it came to be conceived and written as it did. How did The Smoke evolve?

Q. Every book has its own story about how it came to be conceived and written as it did. How did The Smoke evolve?

A. The Smoke began as the first volume of a trilogy (and I’ve not entirely abandoned the idea even now) set in an alternative 1970s London. Obviously there was something in the air. Even as I was working on it, pretty much everyone started playing about in the same corner of the paddling pool. So I stripped what I was doing to the bone, abandoned any notion of “world-building” (which I anyway massively mistrust) and let the narrative dictate what weirdness it would. If you do that, of course, you end up with something inadvertently personal, which is fine by me. If it’s not personal, you’re not writing, you’re just barking.

Q. For all that The Smoke is a novel about alternate histories and potential futures, it also draws from classical mythology. What are some of the influences that inspired its writing?

A. The early reference to Homer’s Odyssey, which comes to underpin the structure of the whole book, was pure serendipity. Sometimes you hit upon a phrase, an image, a conceit, and it proves, by pure happenstance, to be the gift that keeps on giving. Most of the conscious models for The Smoke were post-war northern stories of various kinds: H E Bates stories, Elizabeth Taylor, and especially John Braine’s Room at the Top.

Q. What is the first book you read that made you think, “I have got to write something like this someday!”

A. Frank Herbert’s The Dosadi Experiment made a huge impression on me: I had no idea you could write a conflict from multiple viewpoints and get away with it. On re-reading and mature reflection, I don’t think Herbert got away with it either, not really, not in any satisfying way, but by God the ambition just drips off him. I never did, and never will, write anything like Herbert. That’s okay. It wasn’t his style that inspired me. It was his spirit.

Q. How did you learn to write?

A. By doing. By rewriting. By teaching a little bit. By reading widely. By disappointing other people’s power fantasies about what sort of writer I’d be.

Q. Do you adhere to any particular writing regimen?

A. Right now my life is centered around short pieces, mostly non-fiction, and multiple deadlines. Plus I have a full-time editing job. So long sessions involving the kind of novelistic concentration that wipes you out for the rest of the day aren’t really part of my practice any more. If I’ve the day to myself I will write for an hour, play piano or read for an hour, go back and write into another project for an hour. All very relaxed. I can pull 16-hour days of that sort and never feel particularly weary.

Q. Are you a pantser (someone who writes by the seat of their pants) or a plotter?

A. I plot like crazy. I have a scattergun imagination and letting it loose just leads to a horrible tangle and mess. Plus there’s that line of Stravinsky’ss: The more constraints you impose, the more you free yourself. And the more arbitrary the constraint, the more precise the execution.

Q. What made you choose science fiction as your means of expression?

A. Oh, just happenstance. My father read sf, my elder brother read sf, the house was full of Wyndham and Ballard and Bradbury. People who write sf tend to baff on for hours about their philosophy. They’re desperate to be new, to be cutting edge. I was quite as bad when I started. Eventually the penny dropped: there’s nothing as tired as novelty.

Q. It’s fairly rare for an author to go from writing science fiction to writing about science. How did that progression come about for you, and which do you prefer?

A. Fiction for a general audience is harder for me than science fiction, and non-fiction is the easiest of the lot. If I had private means I would write only fiction, and it would make me a better writer. As it is I get paid to express my beautiful opinions about history and science and art and all manner of other mischief. There are anecdotes tracing how I ended up writing into so many forms but the bottom line is I did what everyone else has to do: I followed the money.

Q: Do you write with any particular audience in mind? Are there any particular audiences you hope will connect with this story?

A. The great tragedy of the writer’s life is that one never really meets one’s audience. The great advantage, though, is that you don’t have to care about them. I can’t think of anything worse, as a reader, than to feel I was being *written at*. Better to think of books as lost kingdoms you stumble upon and explore. My favourite readers are people who come up to me and within five minutes we both realise we have nothing in common. Nothing. It’s a bit awkward at the time but if you think about it, it’s a wonderful thing. It’s First Contact. Primitive communication has been established with the Other through this bizarre bit of technology: a novel.

Q. Tell us why you love your book!

A. Why do I love it? Because it’s a love story. Because it tells the truth about the last five years of my life, which have been important, though not particularly happy. Because it is a novel about science fiction without being, to my mind anyway, a science fiction novel. Not that this is a virtue in itself, of course. But it’s something I’ve wanted to do for a while, and I think I got away with it.

~~~

Author Links

Simon Ings

Twitter

~~~

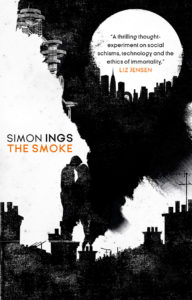

The Smoke was published in the US on January 28th 2019 and may be found at all good booksellers. My review of the book itself may be found here.