Whew, what a year. I’m glad to be here to see the end of it. In late April, at the height of the first wave of the pandemic, I found myself in the hospital for an emergency appendectomy that required a second surgery and several nights in the ICU. It happened like this: one Friday, I had some dental work that involved local anesthetic and true to my long-term form, I needed more than the usual amount. That left me pretty useless for the rest of the Friday, which was not entirely surprising. Saturday seemed normal, though to be honest I don’t much remember it now. Sunday I felt kinda oogly, in the way that happens to everyone from time to time and that hardly ever leads to a visit to the doctor. By 8 Monday morning I could barely walk. Somewhere in there, I had acquired a serious infection, though I didn’t know it yet.

“I’ll go to the ER just to rule out appendicitis,” I said. I listened to sense and took a taxi rather than a bicycle to the hospital, which is about a mile away. (I may have learned from a few years back when I biked a similar distance with a hairline fracture in a leg bone, because I was on the way to pick up a child from daycare that was closing in about five minutes. German closing times are emphatic.) Appendicitis was ruled in, and it wasn’t many hours later that I was wheeled in to surgery.

Modern medicine surely saved my life that day, and again later that week when the infection refused to let go easily. Social distancing saved my life every bit as surely, given that late April was just past the first peak of hospital utilization in Germany. Keeping the medical system from falling over meant that it was working when I, like heart attack or stroke or other critical patients, needed it most. I’m happy to be here and writing.

I was right that I would not keep up my pace of reading from 2019. I read about thirty fewer books this year, ending at 50, my lowest total in quite some time. In the early weeks of the pandemic, I couldn’t concentrate on anything, and re-started by going all the way back to a book that I loved as a third grader. November and December saw me finishing fewer books in two months than I did in some weeks in, say, May. Events weighed on me, even though if asked I would probably not have said that they did.

On the other hand, it was a good year for reading in German. The “München erlesen” (“Munich selections” with a pun on the German verb for reading) series published some years back by the Süddeutsche Zeitung caught my fancy in 2019, and I read another six books from the 20-volume set this year. Eight more to go, one of which is Lion Feuchtwanger’s Erfolg (Success), 750 closely-set pages. It would be by far the longest book for adults that I have read in German.

Also in 2020, I read one book that purports to be mostly translated from German. Definite translations include seven from Japanese (manga volumes not reviewed here), one mostly from Finnish, one from Polish, one from Chinese, and one from Old English. I read 10 books written, edited or translated by women; Wikipedia says that the gender of the author of The Promised Neverland is not known to the general public.

Five of this year’s books were re-reads. I read three full volumes of poetry this year, the most in several years.

Best epic poem and best usage of the word “bro,” Beowulf translated by Maria Dahvana Headley. Best re-read, The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle. Best use of Bavarian dialect, Die Rumplhanni by Lena Christ. Most infuriating stories of corruption, Moneyland by Oliver Bullough. Best geekery, The Soul of a New Machine by Tracy Kidder.

Full list, roughly in order read, is under the fold with links to my reviews and other writing about the authors here at Frumious.

Continue reading

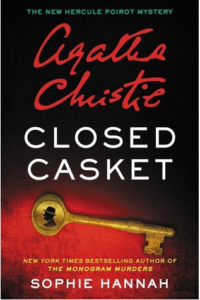

But yes, this is the second novel in Sophie Hannah’s take on the beloved Belgian detective, and I found I liked it less than the two other books in this series that I’ve read. And that’s less, I think, a function of plotting than of pacing and, at least in one significant instance, characterization.

But yes, this is the second novel in Sophie Hannah’s take on the beloved Belgian detective, and I found I liked it less than the two other books in this series that I’ve read. And that’s less, I think, a function of plotting than of pacing and, at least in one significant instance, characterization.