Welp, that’s two five-star amazing children’s books in a row for me, I honestly feel blessed.

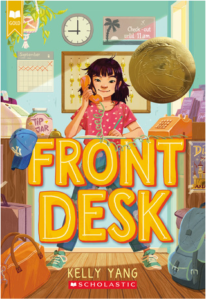

My 8 year-old borrowed this from his teacher, so it’s been sitting, with that compelling cover, on the dining room table where we eat and study and play for a few weeks now. Jms has already finished reading it, and when I finally got a break in my work schedule, I picked it up in order to be able to discuss it with him (and because that cover is adorable!) But also I knew from the blurb that this book was extremely relevant to my interests as an Asian-American immigrant myself.

My 8 year-old borrowed this from his teacher, so it’s been sitting, with that compelling cover, on the dining room table where we eat and study and play for a few weeks now. Jms has already finished reading it, and when I finally got a break in my work schedule, I picked it up in order to be able to discuss it with him (and because that cover is adorable!) But also I knew from the blurb that this book was extremely relevant to my interests as an Asian-American immigrant myself.

Front Desk is about 10 year-old Mia Tang, whose parents have emigrated from China to the USA in the 1980s in search of a better life, free of the vagaries of an oppressive government. Tho her parents are highly educated, the language barrier confines them to low-paying jobs which barely allow them to survive. So when they find an ad looking for someone to manage a motel, with free rent included, the Tang family thinks this could finally be the break they’ve been looking for.

The Calivista Motel is owned by Mr Yao, and from his very first conversation with the Tangs, it’s clear that exploitation is his go-to. But the Tangs, being recent immigrants who don’t know any better, accept his terms, in the same way that millions of other immigrants throughout history have accepted predatory terms due to believing that that’s what it takes to get ahead in America. While her parents struggle to keep up with the day-to-day running and maintenance of the motel, Mia works the front desk when she isn’t at school, where she has a whole other set of problems to deal with, involving popular kids and her own struggles with the English language. As she slowly becomes aware of the unjustness of the situation her parents are in, she also encounters racism, not only to herself and her parents, but also to the motel’s African-American clientele and in particular Hank, one of the weekly tenants.

This would be a complete downer of a novel — an Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle for kids, if you will — if it weren’t for Mia’s belief in the power of words, especially written, to change the world. Her spirit and wit and sheer determination to do the right thing, culminating in one of the most satisfyingly triumphant endings I’ve enjoyed in a while, made for a book that was a sheer delight, even as I sobbed my way through entire, fortunately short because middle-grade, chapters. This was an absolutely tremendous book, and I’m fervently glad my kid’s teacher loaned it to him.

Probably more fervently than my actual kid. We agreed that we both enjoyed the book and had the same favorite parts, but he absolutely was not as affected enough by the proceedings to cry, due to the fact that he’s 8 and has never had to live through that kind of thing. Maybe when he’s older, he’ll revisit this book and understand why his mom loved it so much. I just hope he’ll be lucky enough to have continued to not have to live through that kind of exploitation, but that he’ll have developed an empathy for the less fortunate regardless.

Is it too much to hope that Front Desk, like The Jungle before it, will spur our society to do better, to look on its most unfortunate with compassion, to reform its laws towards more humane purposes rather than less? The current political climate is discouraging, but books like this may at least sow in our young the seeds of a brighter future. And! The sequel comes out in September!! I can hardly wait, but will try to modify my use of exclamation points in the meantime!