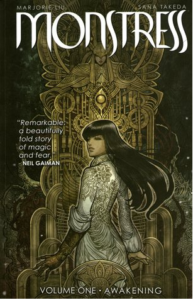

While reading the first volume of this series, I realized that it was going to be one of those comic book titles where you have to hang on for dear life and just enjoy the ride as events unfold and things maybe get explained along the way. The first volume, Awakening, drops you in media res as our heroine, Maika Halfwolf, goes undercover as a slave in order to infiltrate the Cumaean stronghold of Zamora. Maika is a beautiful, human-passing Arcanic whose left arm ends just below the elbow. She’s also host to a monster with a hunger for… well, honestly, I’m not sure exactly what it hungers for, whether it’s killing or blood or life essence or what. Those are the kinds of questions a comic book can skirt around by showing instead of telling, tho sometimes I feel that this series does a lot more showing than explaining at all. Anyhoo, Maika is after a witch, Yvette, who knows what happened to her mother, Moriko, and by extension herself, as Maika finds herself unable to contain the hunger of the monster within her. She figures that Yvette might have answers as to what Moriko found on a doomed expedition where, Maika believes, the monster was put into her. As Maika battles her way through and from Zamora, she picks up a child Arcanic, the adorable fox-like Kippa, as well as Ren, a cat-like double-tailed Ubasti, and learns more about the monster inside.

While reading the first volume of this series, I realized that it was going to be one of those comic book titles where you have to hang on for dear life and just enjoy the ride as events unfold and things maybe get explained along the way. The first volume, Awakening, drops you in media res as our heroine, Maika Halfwolf, goes undercover as a slave in order to infiltrate the Cumaean stronghold of Zamora. Maika is a beautiful, human-passing Arcanic whose left arm ends just below the elbow. She’s also host to a monster with a hunger for… well, honestly, I’m not sure exactly what it hungers for, whether it’s killing or blood or life essence or what. Those are the kinds of questions a comic book can skirt around by showing instead of telling, tho sometimes I feel that this series does a lot more showing than explaining at all. Anyhoo, Maika is after a witch, Yvette, who knows what happened to her mother, Moriko, and by extension herself, as Maika finds herself unable to contain the hunger of the monster within her. She figures that Yvette might have answers as to what Moriko found on a doomed expedition where, Maika believes, the monster was put into her. As Maika battles her way through and from Zamora, she picks up a child Arcanic, the adorable fox-like Kippa, as well as Ren, a cat-like double-tailed Ubasti, and learns more about the monster inside.

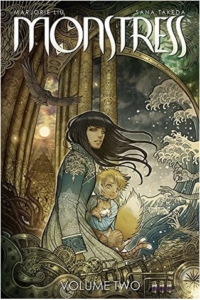

Vol Two, The Blood, finds Maika running toward the pirate-controlled city of Thyria in order to set sail to the Island Of Bones where her mother and Yvette had gone on their ill-fated expedition. Her expedition goes little better, as the monster inside her grows in awareness and offers itself almost as a partner to her. Maika realizes that her mom was an abusive jerk who only created her in order to grow a vessel for the monster. The forces of different interests converge in order to capture Maika and her potential for power for themselves.

Vol Two, The Blood, finds Maika running toward the pirate-controlled city of Thyria in order to set sail to the Island Of Bones where her mother and Yvette had gone on their ill-fated expedition. Her expedition goes little better, as the monster inside her grows in awareness and offers itself almost as a partner to her. Maika realizes that her mom was an abusive jerk who only created her in order to grow a vessel for the monster. The forces of different interests converge in order to capture Maika and her potential for power for themselves.

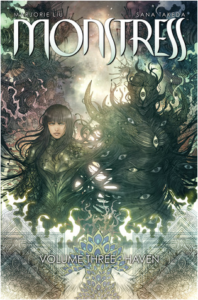

In the third volume, Haven, Maika, Kippa and Ren have made it to the neutral port city of Pontus. However, if Maika can’t re-energize the shield that her ancestor, the Shaman-Empress, once built to protect the city, it’ll be open season on the inhabitants as Maika’s pursuers tear the place apart in search of her and the monstrum, Zinn, she’s carrying within her skin. To this end, she and Zinn must descend into the bowels of the city to open the Shaman-Empress’ lab, and to fight the safeguards long ago put into place to keep it sealed. Zinn remembers a lot more about himself, but not nearly enough, and as in pretty much every volume to date, horrifying shit happens.

So Monstress is a horror comic filled with grotesque images, drawn in a manga style with Western formatting. My favorite thing about Sana Takeda’s art is her gorgeous use of color, plus also Kippa (her tail hugging is the cutest!) and the way she and Ren interact. But otherwise, it’s not for me. I don’t like looking at elder gods and tentacles and a multiplicity of eyes. I’m not a huge fan of panel after panel of violence and killing. And I often feel that the pacing is off, as rando stuff happens that has me going “wait, what” or “who?!” or “why” or “how?!”

But what, you could say, did I expect from a horror story set in an alternate reality loosely based on early 1900s Asia, with steampunk technology and gods who walk among mortals? It’s definitely a cool idea, putting a neat twist on the standard hero’s quest while different races and city-states clash in bloody conflicts and mystical intrigue around her. The world-building is deep, bringing to life a milieu that is believably chaotic. I did very much enjoy the quietly subversive decision to have this be a world run by the matriarchy, with mostly women characters and leaders.

But what, you could say, did I expect from a horror story set in an alternate reality loosely based on early 1900s Asia, with steampunk technology and gods who walk among mortals? It’s definitely a cool idea, putting a neat twist on the standard hero’s quest while different races and city-states clash in bloody conflicts and mystical intrigue around her. The world-building is deep, bringing to life a milieu that is believably chaotic. I did very much enjoy the quietly subversive decision to have this be a world run by the matriarchy, with mostly women characters and leaders.

I think I would have liked the Monstress series a lot more if weren’t so uniformly humorless, tho. There are cute moments and sweet moments, but rarely moments of levity. Again, what you’d expect from a serious horror comic, but awfully hard to sustain over three volumes without making at least this reader fidget with impatience for something other than grimdark. Oh, man, the thought just occurred to me: this is like the feminine version of a Warhammer 40k novel, and not the fun Caiaphas Cain ones either. If that’s your thing, by all means, go for this. I’ve heard so much about the series that I’m glad I finally had the chance to read it (and Vol Two was definitely my favorite of the bunch so far) but it’s definitely not the kind of book I’d pick up by choice ever again. Granted, I still have to read the Hugo nominated 4th volume, and perhaps that’s more my speed. We’ll find out soon enough.