Since my kids started remote learning, I’ve been spending my days as their teachers’ assistant, making sure they are paying attention in class, have all the supplies they need for each lesson and are turning in their assignments. Despite my background in corporate training, my new job as paraeducator is exhausting. People frequently underestimate the benefit of peer pressure in a contained environment in getting little kids to stay on task and behave, so I have a lot of sympathy for the educators doing their best to corral a screen full of rambunctious kids when I can barely get my three to sit up straight and engage. I thought I hit my nadir last week when I was running from room to room, helping the teachers figure out what each kid needed even as another kid was yelling for help from where he’d sequestered himself, but then today my eldest dropped and smashed a light bulb on the kitchen floor while I was trying to ferry workbooks and crayons to where each twin was perched in the living and dining rooms. I’m fine in body but feeling considerably rumpled, to put it mildly, in spirit.

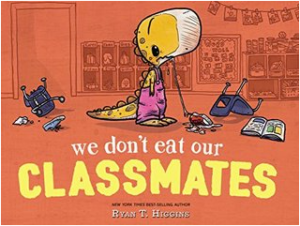

So it’s always a bit of a treat to get to the reading portion of the day, when the 6 year-olds and I can sit down and watch a video of a picture book being read (while the 9 year-old is hopefully being productive on his own Chromebook.) We’ve done our fair share of Pete The Cats and other well-meaning, earnest kids’ books, so I was expecting more of the same from their latest social studies class, where we’ve been working on books about getting used to the new school year. But then teacher put on this video for Ryan T Higgins’ We Don’t Eat Our Classmates.

So it’s always a bit of a treat to get to the reading portion of the day, when the 6 year-olds and I can sit down and watch a video of a picture book being read (while the 9 year-old is hopefully being productive on his own Chromebook.) We’ve done our fair share of Pete The Cats and other well-meaning, earnest kids’ books, so I was expecting more of the same from their latest social studies class, where we’ve been working on books about getting used to the new school year. But then teacher put on this video for Ryan T Higgins’ We Don’t Eat Our Classmates.

Y’aaaall. My jaw dropped as we followed Penelope the little T-Rex as she prepares for her first day of school. The other kids don’t like her because, as the title suggests, she keeps trying to eat them, and as the book progresses she learns a valuable lesson in empathy and self-regulation. It’s a short book and I’d rather not include any spoilers here, but I will say that I yelped with laughter as it was read (and only partly due to Awnie’s excellent narration.) The twins seemed less impressed, tho at least they sat through the entire thing, which is more than they often do with other titles. I loved it, tho, and only partly because it reminded me of Patrick Rothfuss and Nate Taylor’s hilarious The Thing Beneath The Bed. While that volume featured some delightful line drawings, I think I enjoyed Mr Higgins’ full-color illustrations even more, especially given the diversity of Penelope’s classmates (and one terrifying goldfish!)

But more importantly, WDEOC serves as a nice counterweight to all the titles that encourage kids to be proud of their individuality and to look for friends who will make them feel appreciated and supported. While those are important lessons, they don’t mean that your friends should be your doormats, especially if your behavior is truly harmful. WDEOC uses a humorous worst-case scenario to remind kids that actions have consequences, and that friendship is a two-way street. It’s a great picture book addition to any kid’s library, especially if that kid has a bit of a mean or selfish streak that you’re trying to train them out of. Best to teach them how to empathize as a little one, after all, than to try to do it years later, when it may be too late and they’re ranting against wearing masks around others or engaging in other appalling antisocial behaviors.