In some distant and ultimately irrelevant future, humanity has mastered time travel and discovered not a single causal chain through the unity of time and space, but a vast multitude of timelines. They cluster in groups of similar development. In some, humanity spreads to the stars; in others, humanity remains more tightly tied to its origins. Perhaps inevitably, strife follows humans not only to the stars but throughout all of accessible time. The book does not say how the two factions — Garden and Agency — came to be, nor which, if either of the two, discovered time travel.

As the book opens, the two sides are at war and have been for an immeasurable span of time. They have incompatible visions of the future, and of the past and present for that matter. They represent different modes of living, of development. Garden is all about growing and cultivating, though of course they keep the technology required for travel through time and space. The Agency is a more mechanized future, where devices serve humanity and support civilization. If sometimes the line between people and machines blur, well, it has been that way at least since the first glass sphere purported to replace an eye. And the people that Garden grows in pods, well, humanity was tied to cultivation before history began.

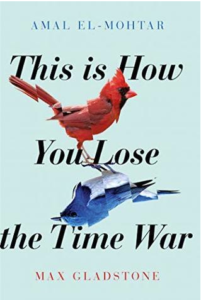

But This Is How You Lose the Time War is about neither the technology and paradoxes of time travel, nor the two visions and factions that define time-traveling humanity. It is a love story.

In their neverending war, the Agency and Garden agents who climb up and down the timelines attacking each other’s crucial developments while defending their own, trying to cut the other faction off at the temporal pass while ensuring that enough of their own timeline clusters survive and thrive to provide for ultimate victory. The agents are functionally immortal, and while enemy action can kill one they can take an enormous amount of damage before expiring. They are also seasoned killers, both on vast scales in battles of fleets and up close and personal in bloody hand-to-hand encounters. Naturally, some agents are more effective at achieving their ends than others. The agents, or at least the better agents, have distinctive styles of operation, and after enough opposing encounters, the better agents can recognize one another’s handiwork.

On a battlefield that Red, and Agency agent, has engineered to bring about a clash of armies that will lead to the death of the planet it is set on, she finds something that should not be there — a letter, “a sheet of cream-colored paper, clean save a single line in a long, trailing hand: Burn before reading.” (p. 4) She says to herself that of course it is a trap, that “The smart and cautious play would be to leave. But the letter is a gauntlet thrown, and Red has to know.” (p. 5) The letter also means that an agent of the Garden has been there, and thus that her successful mission has in some sense been a failure, too. The letter, from an agent who signs herself as Blue, is in fact a gauntlet, not exactly an opening move but a change in the game they have been playing since well before the book began.

You’re wondering what this is—but not, I think, wondering who this is. You know—just as I’ve known, since our eyes met during that messy matter on Abrogast-882—that we have unfinished business.

I shall confess to you that I’d been growing complacent. Bored, even, with the war, your Agency’s flash and dash upthread and down, Garden’s patient planting and pruning of strands, burrowing into time’s braid. Your unstoppable force to our immovable object; less a game of Go than a game of tic-tac-toe, outcomes determined from the first move, endlessly iterated until the split where we fork off into unstable, chaotic possibility—the future we seek to secure at each other’s expense.

But then you turned up.

My margins vanished. Every move I’d made by rote I had to bring myself to fully. You brought some depth to your side’s speed, some staying power, and I found myself working at capacity again. You invigorated your Shift’s war effort and, in so doing, invigorated me.

Please find my gratitude all around you.

I must tell you that it gives me great pleasure to think of you reading these words in licks and whorls of flame … In order to report my words to your superiors you must admit yourself already infiltrated, another casualty of this most unfortunate day.

This is how we will win.

It is not entirely my intent to brag. I wish you to know that I respected your tactics. The elegance of your work makes this war seem like less of a waste. (pp. 7–8)

Blue signs the letter “Fondly,” knowing that both letter and closing will provoke Red. And so they are off: masters of war, artists of battle, sculptors of the timescape. After the first letter they take turns leaving notes for their best and favorite adversary, touting the righteousness of their own cause, pointing out the flaws in their counterpart’s tactics, signing their own work with a flourish and a challenge. El-Mohtar and Gladstone show readers what neither Red nor Blue fully notices, that a shadow follows both.

Is it any wonder that the two fall for each other? Nobody else can match the artistry of their brutality, the subtlety of the destruction that they cause. Each appreciates the other, even as their respective commands see flaws and begin to harbor doubts. Over the course of most of the story, they do not meet, they cannot meet. But in the letters that they leave for each other they reveal themselves; eventually they make themselves vulnerable and call Garden and the Agency into question.

All of it is exquisitely crafted. El-Mohtar and Gladstone portray Red and Blue as special people, finely attuned to temporal causation, capable of subtle workings that have ramifications far beyond their initially visible effects. An epistolary romance across time and space, star-crossed because of their commitments to their causes, I can see how it captured many readers’ hearts and imaginations. Red and Blue know each other as they would like to be known, as nobody else can know them, not through a timeglass darkly but in secret letters space to space.

In the end, though, I didn’t warm to the romance because I never got over my initial impression of the two agents as bloody killers. Nobody else besides Red and Blue really matters in This Is How You Lose the Time War, though the respective heads of Garden and the Agency are implied to have enough power to put the two agents permanently out of action. All the others, with the possible exception of the shadow, are mere props. Which is fine, I suppose, as an artistic choice. El-Mohtar and Gladstone are writing a romance à deux, and at a length that does not allow for much more. They hold to their focus, and they execute it admirably. For my part, though, I never stopped thinking of the millions of other lives dealt casual destruction, and even though the end of the novella points toward something other than endless war, I remained uncharmed.

+++

Doreen’s review is here; she liked the concept more than the execution.