I have more than a sneaking suspicion that Ben Aaronovitch wrote Amongst Our Weapons to deliver one particular joke. People who recognize the source of the book’s title will expect that some variation on the joke is coming, but they will have to wait until page 287. Nightingale delivers the setup in Latin, though he also helpfully translates. Postmartin, the Folly’s helpful archivist, gives the context. Detective Chief Inspector Alexander Seawoll, who has been roped into another case full of what it pleases him to call “weird bollocks,” gets the crucial line. But because it’s a joke from outside the text, Aaronovitch barrels along with the story which, three quarters of the way through, is getting quite tense by then. I kept chuckling to myself, satisfied by perfect delivery.

It’s fitting that Seawoll provides the iconic line because the clues in the novel’s mystery lead Peter Grant and the other magical investigators from London well up into the north of England, Seawoll’s home turf. Across the last few novels, Aaronovitch has been showing more of the irascible DCI, hinting that there are methods to his Mancunianness and demonstrating not only growing understanding between Seawoll and Nightingale but also hinting that he has more respect for Peter’s potential than his abrasive manner would suggest.

The case begins in proper Rivers of London fashion with a grisly death that could not have happened by mundane means. In this instance, a visitor to one of the shops in the London Silver Vaults — a real and very secure set of underground shops that began as strongrooms but have been selling places since the late 1800s — had died of whatever had produced a perfectly round hole about a hand’s width across in both his clothing and his body. Whatever it was stirred enough magic to fry all the closed-circuit cameras in the area, and strange enough to erase vestigia, the usual traces that magic leaves on objects and their surroundings.

Police work, magical and otherwise, establishes that the unfortunate visitor had been looking for a ring, and eventually that this ring was one of a set given to a group of spiritual seekers in the late 1980s. What is the connection? Are the others in danger? Or are they suspects? Amongst Our Weapons is a solid Rivers of London mystery. Both the Folly as an institution and the lead characters are developing; this is not a series that returns to the status quo at the end of each episode. Aaronovitch reins in some of the sprawl that I was starting to feel as I read False Value. He does not feel the need to check in with each character who has become important, and he is confident enough to let developments take place off the page and only clue readers in when the natural course of this story intersects with the other characters.

The trail of clues eventually takes Peter and the rest up to the north of England, where the weather is fitting, and yet more discoveries about magic and the island’s history await. For a solution, they have to return to London of course, because the series isn’t Rivers of West Woodburn, is it?

Aaronovitch has written five novellas in the Rivers of London series. I think that the first, The Furthest Station, was something of a proof of concept. Were there stories in the setting suited to novella length? Could he write as well in the shorter length? Yes and yes, as far as I am concerned. It seems that his publisher agreed, and he wrote four more. Interestingly, The Furthest Station is the only one that is a Peter Grant story. Each of the others also has a season of the year as setting and important thematic element. The October Man is set in autumn in Germany and only has a slender connection to the other works in the set. What Abigail Did That Summer is obviously a summertime story, and just as obviously stars Peter’s precocious cousin Abigail. Aaronovitch uses the novellas to explore other characters, other places, and maybe to test drive combinations for future full-length novels.

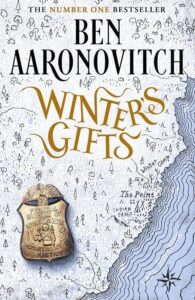

Winter’s Gifts follows Kimberly Reynolds, an FBI agent who has turned up in previous books and developed a good working relationship with Peter. She has become a semi-official liaison between British and American practitioners in law enforcement. (Official-official channels are still poisoned by bad blood from World War II and, in all probability, the American Revolution.) American agencies seem to have ignored magic for decades, and in Winter’s Gifts the structures needed to deal with odd incidents are so out of date that practically nobody even remembers them. Which is how Patrick Henderson, a retired FBI agent who was part of the Bureau long ago enough to know the code phrase, puts through a warning call that makes its way through channels until someone decides that Reynolds’ lap is the right one for it to land in.

Unfortunately, by the time that she receives the warning and makes her way to Henderson’s town in northern Wisconsin he has gone missing under very odd circumstances. Said circumstances also include an ice tornado that emerged from a weather pattern that had never before been known to spawn tornadoes. Even more unfortunately, winter weather that’s harsh even by local standards continues to close in, effectively cutting the town off, and definitely cutting Reynolds off from additional support from the Bureau. She’s on her own investigating what might be a very powerful magical source, possibly tied to Native practitioners and genius loci tied to Lake Superior. The setting is good, the mystery is terrific, the action is tense; Winter’s Gifts was a fun and satisfying story. Aaronovitch writes in first person from Reynolds’ point of view, and I think he didn’t quite catch the character. Reynolds is from a fundamentalist and politicized evangelical background — she describes her mother’s knee-jerk distrust of Washington, for example — but those parts of her story still read to me more like a British person’s idea of far-right America than the kind of people I knew on that spectrum. Points to Aaronovitch for stretching beyond his tried-and-true, but it may take a couple more outings for him to write truly about America and people like Reynolds. One of my favorite aspects of the series is how much it is a love letter to London, and that just can’t be present in a story set across the Atlantic.

The Masquerades of Spring is set not only across the Atlantic, but many decades previous in Jazz Age New York. This novella is a Nightingale story but told by one of his contemporaries rather than the man himself. Augustus Berrycloth-Young, Gussie to select friends and former schoolmates such as Nightingale, is an Englishman in New York, enjoying the many delights the city has to offer and doing just enough for the Folly for them to prefer him being over there rather than at home. Gussie is very full of himself, but moderately aware of that, and he tells the story in the self-conscious style of a very gay Edwardian gentleman fetched up in the New World. He has arranged himself very well to the circumstances, acquiring a very capable Black butler named Beauregard, and plunging into the culture and nightlife the city has to offer. Nightingale’s sudden appearance, he knows, portends something dashedly inconvenient, if not worse.

I enjoyed seeing a much younger Nightingale, who is headstrong, almost as good a practitioner as when he meets Peter Grant, and who does not yet have the melancholy that the events of World War II laid upon him. He’s also still learning his way around people, and makes the occasional mistake with Gussie. The magical adventure itself takes Nightingale and Gussie into New York’s criminal underworld, its jazz clubs and speakeasies, and into its Black and gay communities. I haven’t read enough Wodehouse to know whether Aaronovitch is doing some amount of pastiche with Gussie and Beauregard, though there are fake ads in the back of The Masquerades of Spring for additional books about adventures the two have, so I think that’s likely. The pace is fast, the surprises and reversals furious, and the resolution both spectacular and true to the period. I hope that there will be more tales from Nightingale’s past.