Like many children who grow up in peculiar families, Ru does not realize just how peculiar his home life is. As he gets bigger, he starts asking questions. Who am I? Who are we? Where do we come from? The second two are particularly important in in Bowbazar, the Calcutta (the spelling that Das uses throughout the book) neighborhood where Ru’s small family lives in a large house with a Chinese restaurant in the front part. When he is in his first years in school, his mother answers the third with “You wouldn’t believe it if we told you.” (p. 13) Later on, she gives a bit more. “We come from nomadic people. We move around. There are many of us around the world, but we’re solitary, and don’t like to draw attention.” (p. 16)

Readers will know more from this novella’s title, and from the memory of Ru’s that Das uses as its opening anecdote. He remembers being small, and in the garden with his grandmother, who was tending a bush low to the ground.

It wasn’t a seed pod at all. With practiced care she nudged open the curled, broad leaves, unwrapping it to reveal what was inside.

The broad petals of the pod were the brown wings of a creature that fit gently in the pink cradle of my grandmother’s palm like a bat. Its tail was the thin stem that connected it to the branches of the tree. And curled inside the embrace of its own wings was the contracted body of the beast, its six limbs clutched to its torso in insectile fragility, its sharp and thorny head like a flower’s pistil, the curled neck covered in a dew-dusted mane of white fur like the delicate filaments of a dandelion seed. The gems of its eyes were left to my imagination, because they were closed in whatever deep sleep it was in.

“It’s a dragon,” I said, to encase the moment in the amber of reality.

“Yes it is,” said my grandmother with a proud smile. Whether this was pride at me or the little dragon whose papery brown wings she was touching, or both, I can’t say. “Here, we call it the winged rose of Bengal.”

It was the most beautiful thing I’d seen in my life. I remember the immensity of the happiness I felt, looking at this flower-like fetus of a dragon growing off a tree tended to by my grandmother, knowing that dragons were actually real and grew on trees, wondering if people knew.

I couldn’t really believe it, which is why the memory became a dream. I convinced myself it wasn’t a true memory, because dragons don’t exist. (pp. 10–11)

Later, he forgot the details. Still later, he remembered some of them and asked his family about dragons. They told him he had a dream. Even later, he became aware that he was missing many memories because drinking the Tea of Forgetting was a regular ritual for the only child in his home. But not everything stayed forgotten.

Das interleaves the story of Ru growing up and his misadventures among the boys at school with further memories from unspecified times. One evening, Ru does not ask his mother where they are from. He asks why his parents won’t let him remember. “She blinked. ‘You deserve to be real in this world. It’s not an easy thing to be stuck between worlds.'” (p. 34)

Ru feels stuck between worlds all the same, different from the other boys, and eventually taken out of school when his parents feel his schoolmates’ questions, and the stories he tells to quell their curiosity and gain their respect, could become dangerous for the family. Only once is he allowed to have friends over to his house, and at the end of the lunch at the Dragoners’ Club of Bombay (Est. 1942) the other boys drink the Tea of Forgetting so they are left with the impression of a fun afternoon and no clear idea of how to go back to Ru’s. They will never know that they dined on dragon.

Growing into his teen years changes Ru’s friendship with Alice, the daughter of the Chinese family who runs the restaurant at the front of his house. She sees and likes him for who she is, and she’s intrigued by how further back in his family’s history there seemed to be far fewer distances between men and women. She likes his long hair, his sincerity, his difference. The friendship blossoms, but it’s also unequal: Alice goes to a co-educational school and has plenty of friends; Ru has tutors at home and seldom ventures beyond the house and garden. It is, in some ways, a whole world, full of mystery and secrets. Ru and Alice pry into some of them, and mostly escape getting more than they bargained for.

But the house and the family are not in a stable equilibrium. Just as Ru cannot stay in childhood forever, neither can the extended family or the people of whom they are a part stay as they were. In the end, things change — Ru learns what he has forgotten and more. The end is just a beginning. The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar is beautiful, though it has many dark corners. Das gets the length just right, telling the tale in full without overburdening it with more details than its structure could support. And in answer to a question that Ru poses very near the end, it’s not flimsy, not flimsy at all.

4 comments

Skip to comment form

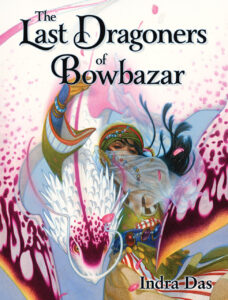

I’m kinda obsessed with that gorgeous cover! The interior sounds like it matches perfectly, too!

Author

It is gorgeous and it does match the story! Plus the hardback is a signed limited edition that feels great, too. My copy is like #817 or something out of 1000, so there’s still time.

Speaking of stunning books, I got the 25th anniversary edition of Little, Big (published just in time for the 40th anniversary) and zomg it’s amazing. Total booklust.

Oooh, have you posted photos anywhere? I read Little, Big over a decade ago, I want to say. It was fine but not what I was looking for at the time, I believe. One of those books you know are worthy and you’d likely enjoy at a different time of life.

Author

I haven’t posted photos, but that’s a good idea! The edition is gorgeous.

The book divides opinions, even among people who you might expect to like that sort of thing. One of my co-bloggers from A Fistful of Euros also once observed that Little, Big strategically deploys boredom as part of its art, and yow is that a big risk for an author to take. People surely nope out during those stretches. I haven’t re-read it in ages, but I about wore out my Bantam paperback, and I feel like I should have a trade paperback edition around here somewhere that I picked up to avoid finally reading my original copy to death. So it’s been a bit of a touchstone.