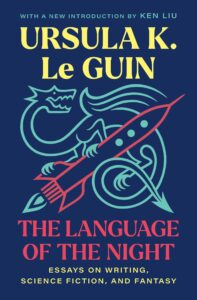

I should have read the description of The Language of the Night more closely because when it arrived I was a little irritated to discover that it’s a collection of essays mostly from the early and mid-1970s, with some footnoted and additional remarks that Le Guin added to a new edition of the book in 1989. To be sure, there is also a 2024 introduction by Ken Liu, but that did little to temper my sense that the essays are, by now, essentially period pieces, historical artifacts of an era nearly half a century past.

On the one hand, this edition of the book is itself an example of the kind of dialog — or at least serial monologues — that Le Guin wanted to foster and that she maintained were essential for the health of a literary field. There are her original essays from the 1970s, some written to work things out for herself, others written as introductions to her earlier novels as they were reprinted for wider audiences, still others derived from talks and presentations. The first edition of the book was edited by Susan Wood, a critic and professor of literature at the University of British Columbia. She provided a general introduction to the volume and more specific ones for each of the book’s five sections. The general introduction quotes (and provides a citation for) a wonderful piece of Le Guin lore. It’s a bit of an interview from 1975 that illustrates how science fiction was widely perceived at the time, and what Le Guin thought about that perception:

Jonathan Ward: Which would you rather have, a National Book Award or a Hugo?

Le Guin: Oh, a Nobel, of course

Ward: They don’t give Nobel Prize awards in fantasy.

Le Guin: Maybe I can do something for peace.

(pp. xxxvi–xxxvii)

Doris Lessing, who unquestionably wrote science fiction, won the Nobel Prize in 2007.

For the 1989 edition, Le Guin wrote a new introduction and added footnotes in a number of places to illustrate how her views, particularly on gender and feminism, had changed in the decade-plus since the book’s first publication. She made the most substantial revision to her essay on The Left Hand of Darkness, “Is Gender Necessary?” That work is published in the present volume as “Is Gender Necessary? Redux” in a two-column format, with her original essay on the left and her significant commentary on the right. She changed her mind on a number of things in between the two editions, most importantly on no longer accepting “he/him” as generic pronouns in English prose, opting either for the singular “they,” or re-casting sentences entirely to do without the pronouns.

On the other hand, The Language of the Night collects essays from a time when science fiction was very different, and its place in both literature and the culture as a whole were very different. In the book’s final essay, she writes “Maybe one out of thirty SF writers is a woman. That statistic is supplied to me by my agent, Virginia Kidd … the ratio is a guess, but an educated one.” (p. 250) That has changed tremendously, as the last decade or so of the field’s top awards demonstrates. She often writes about science fiction as disdained by publishers and literary establishment alike, something found in a bookstore on “Shelf 63, between the Gothics and the Soft Core Porn.” (247) That’s a problem from a different era; science fiction has won. Unfortunately, that relegates some of her views to merely historical interest.

[Getting vain and hasty] is a real danger when you write science fiction. There is so little real criticism that, despite the very delightful and heartening feedback from and connection with the fans, the writer is almost her only critic. Second-rate stuff will be bought just as fast, maybe faster, by the publishers, and the fans will buy it because it is science fiction. Only the writer’s conscience remains to insist that she try not to be second-rate. Nobody else seems much to care. (p. 12)

Not anymore.

Fortunately, she held true to the end of that same essay, published when The Dispossessed had been written but not yet released:

Meanwhile, people keep predicting that I will bolt science fiction and fling myself madly into the Mainstream. I don’t know why. The limits, and the great spaces of fantasy and science fiction are precisely what my imagination needs. Outer Space, and the Inner Lands, are still, and always will be, my country. (p. 13)

The whole thesis of “Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown” is that vivid characters of the sort written by Dickens and Woolf were vanishingly rare in science fiction, and that the genre as practiced in 1975 seemed incapable of producing them. Being a literature of Ideas, when science fiction was good and of cut-out figures when it was bad, had crowded out the creation of people on the page who would remain with readers long after they set the story down. This is another area where the genre has definitively changed for the better.

I thought that the strongest section of the book was “The Book Is What Is Real,” the collection of five introductions to her novels, viewed anywhere from a few years to more than a decade after their initial publication. Le Guin discusses what she wanted to to, where she thought she fell short, and what she still saw as the novels’ virtues. The essays are good for their specific application of her more generalized ideas, and for the chance to listen to an artist muse about her own development.

Le Guin’s essays are never less than enjoyable to read, but many of them in The Language of the Night have become dated as their half-century mark approaches. The books shows one writer’s evolution, and where she thought the field was at the time. The former will be interesting as long as Le Guin is read; the latter is mainly of historical interest.