The writing of Jozef Czapski persuaded me to read Proust, and the writing of Marcel Proust persuaded me to stop. Czapski noted that Proust wanted popular success, and that one of the first translations of Proust into Polish had made him popular in that language, in part by rendering his famously extended sentences into more usual lengths for Polish prose. Warsaw wits then averred that the way for Proust to gain popular success was to translate him from Polish back into French. Of course the newish (2002) translation by Lydia Davis did not take that approach. In her rendition, Proust’s sentences are intact, in all of their recursive glory. I can’t say that I found the style a particular stumbling block; I would not have made it through a thousand pages of The Magic Mountain if complex sentence structure irritated me. The problem was much more fundamental: Proust left me indifferent to his characters and their world.

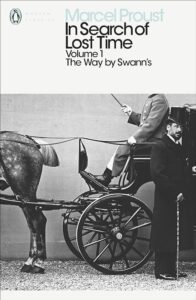

The Way by Swann’s — often translated as Swann’s Way, and indeed both the translator of this volume and the general editor of the complete translation of In Search of Lost Time have seen fit to discuss the proper translation of the title, at noticeable length, in their respective introductions — is the first of seven volumes that comprise Proust’s novel À la recherche du temps perdu. (The edition whose first volume I have combines The Prisoner and The Fugitive into a single book, so it is six volumes as published.) The Way by Swann’s is divided, like Gaul, into three parts: “Combray,” “A Love of Swann’s,” and “Place Names: the Name.” The first is mostly recollections from the narrator’s childhood in the eponymous town, mostly based on Proust’s own childhood in the village of Iliers in north-central France. Charles Swann, who lent his name to both the love and the way, is a wealthy, socially connected man of the narrator’s family’s acquaintance. The middle section is set quite a few years before the first and third. It tells of Swann’s love for, and eventual apparent indifference to, a former courtesan named Odette, along with many dinners and social occasions on the way from infatuation to disdain. The third part returns to the direct experience of the narrator as a boy, this time in Paris. Readers may be surprised to find that Odette has become Madame Swann, and mother to a daughter named Gilberte. When, how and why did the relationship between Swann and Odette change? This book does not say.

The narrator, though obviously young, falls for Gilberte in a way that mirrors Swann’s earlier obsession with Odette. There are some charming scenes of play along the Champs Elysées; there are some cringe-inducing scenes of a boy’s expectations of a girl. In the book’s final pages, the narrator, presumably much older, muses on how the elegance of his boyhood years has declined into automobiles, bad taste in colors, and lack of gardeners tending the Bois de Boulogne. The end. Of the first volume, at least; readers who persist to the final end have another 2500 or so pages ahead of them.

The Way by Swann’s is not uniformly tedious. There are great swathes of the book where Proust is clearly having great fun with his sentences. As they approach 200 words, he is having a ball keeping all of the clauses up in the air, managing the lists, the commas, the filigrees, the digressions and his other impressions, without utterly abandoning the through-line or, one, or presumably the author at least, hopes, without completely losing the reader. Here are two, more or less at random, in case any of my readers want to have an example at hand when a bit of writing gets described as “Proustian”:

Darkened by the shade of the tall trees that surrounded [the park], an ornamental pond had been dug by Swann’s parents; but even in his most artificial creations, man is still working upon nature; certain places will always impose their own particular empire on their surroundings, sport their immemorial insignia in the middle of a park just as they would have done far from any human intervention, in a solitude which returns to surround them wherever they are, arising from the exigencies of the position they occupy and superimposed on the work of human hands. So it was that, at the foot of the part that overlooked the artificial pond, there might be seen in its two rows woven of forget-me-nots and periwinkles, a natural crown, delicate and blue, encircling the chiaroscuro brow of water, and so it was that the sword-lily, bending its blades with a regal abandon, extended over the eupatorium and wet-footed frogbit the ragged fleurs-de-lis, violet and yellow, of its lacustrine sceptre. (pp. 137–38)

Proust is sometimes quite funny, especially when he is being mean. Of the village curé, Proust has the narrator write that he was “an excellent man with whom I am sorry I did not have more conversations, for if he understood nothing about the arts, he did know many etymologies.” (p. 104) Late in the book, he discourses on men and their monocles:

The Marquis de Forestelle’s monocle was minuscule, had no border and, requiring a constant painful clenching of the eye, where it was incrusted like a superfluous cartilage whose presence was inexplicable and whose material was exquisite, gave the Marquis’s face a melancholy delicacy, and made women think he was capable of suffering greatly in love. But that of M. de Saint-Candé, surrounded by a gigantic ring, like Saturn, was the centre of gravity of a face which regulated itself at each moment in relation to it, a face whose quivering red nose and thick-lipped sarcastic mouth attempted by their grimaces to equal the unceasing salvoes of wit sparkling from the disk of glass, and saw itself preferred to the handsomest eyes in the world by snobbish and depraced young women in whom it inspired dreams of artificial charms and a refinement of voluptuousness; and meanwhile, behind hiw own, M. de Palancy, who, with his big, round-eyed carp’s head, moved about slowly in the midst of the festivities unclenching his mandibles from moment as though seeking to orient himself, merely seemed to be transporting with him an accidental and perhaps purely symbolic fragment of the glass of his aquarium, a part intended to represent the whole… (pp. 329–30)

Such sentences could occasionally carry me happily along, but the fact is that since I began Proust’s first volume in early January, I have finished 27 other books before coming to the end of The Way by Swann’s. Of all the many thousands of words in the book, the most apt for me were the eight deadly ones: I don’t care what happens to those people.

2 comments

2 pings

I’m actually loving it so far, and the labyrinthine sentences are a highlight for me.

Author

Glad you’re enjoying it, and thanks for stopping by here to read our work!

[…] Chatwin: The Songlines 38: Botho Strauß: Paare, Passanten (Couples, Passers-by) 39: Marcel Proust: Swann’s Way 40: John Steinbeck: Tortilla Flat 41: Andrzej Szczypiorski: The Beautiful Mrs Seidenman 42: […]

[…] to German (Der Tod eines Bienenzüchters), from Korean (Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982), from French (The Way by Swann’s), and from Spanish to German (Landschaften nach der Schlacht). The three translations into German […]