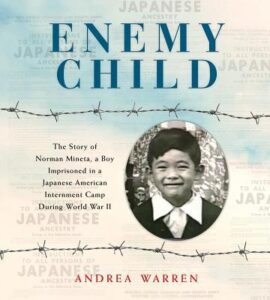

subtitled The Story Of Norman Mineta, A Boy Imprisoned In A Japanese American Internment Camp During World War II.

Many Americans will know of Norman Mineta as a trailblazing Japanese American politician, a moderate Democrat who served in both Democratic and Republican cabinets. He always resisted having any books written about his life until he was approached by Andrea Warren, an award-winning author of books for children, who wanted to make his story accessible to young readers and beyond. Together, they worked on what would be the only biography of him ever written in his lifetime, focusing primarily on how he along with tens of thousands of other Japanese Americans were unjustly incarcerated during World War II.

Many Americans will know of Norman Mineta as a trailblazing Japanese American politician, a moderate Democrat who served in both Democratic and Republican cabinets. He always resisted having any books written about his life until he was approached by Andrea Warren, an award-winning author of books for children, who wanted to make his story accessible to young readers and beyond. Together, they worked on what would be the only biography of him ever written in his lifetime, focusing primarily on how he along with tens of thousands of other Japanese Americans were unjustly incarcerated during World War II.

Norman was your average kid growing up in San Jose, California in the 1930s and 1940s. While his parents were immigrants from Japan, they weren’t allowed to apply for citizenship based on the discriminatory laws of the era. Norman and his four older siblings were all born in the United States however, making them just as American as any of their neighbors, Asian, white, Black or otherwise. While Japanese culture was a big part of the Minetas’ daily lives, they wholeheartedly embraced being American too, and were deeply grateful to be able to live free in ways not possible across the Pacific Ocean.

The outbreak of World War II, alas, made it a bad time to be an American of German, Italian or Japanese descent. While many community leaders from all three backgrounds were detained under suspicion of conspiracy with the enemy, only Japanese Americans were ultimately forced to leave their homes and move to internment camps en masse. Norman was one of the many children shipped off with his family to live in reprehensible conditions, as Ms Warren unflinchingly details in her tightly written, thoroughly documented accounting.

Yet the Japanese spirit of resilience ensured that the vast majority of internees managed to not only survive but thrive. The internees by and large chose to cooperate fully with government directives, in an effort to prove that they were as deeply loyal to America as they always said they were. Which doesn’t make what happened to them at all excusable. The Mineta family were lucky in that, when the war ended several years after they were ripped from their homes, they could return to San Jose to find that their neighbors’ unwavering faith in them had protected their property and belongings. Many others returned to nothing, or worse. Anti-Japanese sentiment had run high during World War II, and did not abate immediately with the cessation of hostilities.

Norman was well aware of all this, and suitably wary in his own day-to-day dealings. But he was also the beneficiary of a diverse hometown that appreciated his contributions from childhood and beyond, as he eventually became mayor of San Jose before being elected to the House of Representatives. Tho racism did not leave him unscarred, the can-do American spirit that leans almost inevitably to sheer decency ensured that he always had the chance to not only advance politically, but to represent and give back to his community as well. Passing the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 — which provided both an apology to Japanese American internees as well as financial reparations — with bipartisan support was what he considered the crowning achievement of his career. As Secretary of Transportation when the 9/11 attacks happened, he was also instrumental in fighting any ban against passengers based on appearance or religion.

It’s unusual that so public a figure would have no other authorized biographies, but reading Ms Warren’s book makes it perfectly clear that Norman Mineta was never looking for acclaim. His fight for justice was very much embedded in the desire to ensure that what happened to him and other innocent Americans never happened to anyone else. What better way to plant the seeds for this than by having his story written in a format targeted towards children, but just as accessible to be read by anyone older? Despite using straightforward language and an even tone throughout, however, Enemy Child is neither a fast nor an easy read. It’s heartbreaking to think of what the internees went through, but inspiring to see how they overcame one of the worst violations of their constitutional and human rights in order to reclaim their rightful places as Americans once more.

On a personal note, I’m actually a little surprised that I’ve never been to the Japanese American Memorial for Patriotism here in DC (tho I would hardly describe it as being close to the White House, as the book does, when landmarks like Union Station and the Capitol are in far closer proximity.) Since it’s unlikely that I’ll be able to visit one of the internment sites run as a memorial by the National Parks Service in the near future, I’m going to make a point of visiting this memorial, in honor of a boy who survived one of the greatest injustices of American history to become a leader in the ongoing fight to ensure that it never happens again.

Enemy Child by Andrea Warren was published April 30 2019 by Margaret Ferguson Books and is available from all good booksellers, including