“What kind of a life do you lead where you find yourself building a dog of bones?” (p. 2) Marra asks herself, though of course she knows. It’s the readers who want to know how she has come to this distinctly creepy, slightly mad pass. And she’s come to it wearing a cloak of owlcloth tatters and spun-nettle cord, made in a day by her own hand. “Even the dust-wife said that I had done well, and she hands out praise like water in a dry land.” (p. 2) What’s a dust-wife? She keeps putting the dog together, in a “blistered land” inhabited by cannibals and the things that scared them. Marra keeps repeating a jump-rope rhyme, and it works a bit of magic. “Bone dog, stone dog … black dog, white dog … live dog, dead dog … yellow dog, run!” (p. 9) And the bone dog comes alive at dusk.

The love of a bone dog, she thought, bending her head down over the paw again. All that I am worth these days.

Then again, few humans were truly worth the love of a living dog. Some gifts you could never deserve. (p. 8)

The book’s back cover gives away what it would otherwise take several chapters for a reader to discover, as T. Kingfisher (who also writes under her given name of Ursula Vernon) doles out background at a deliberate place, jumping back and forth between Marra’s odd and dangerous present, and a past that seemed less threatening at the time. She was a princess — youngest of three — of the Harbor Kingdom. The sisters do not get along, and the kingdom itself is in a precarious position. It is sandwiched between covetous neighbors, both of which would like the eponymous harbor, but who also want to deny it to their rival. The balance tips, though, and the oldest sister is sent to marry the prince of the Northern Kingdom in a protective alliance. Five months later she comes home in a coffin. The prince is said to be heartbroken. It is said that she fell down a flight of stairs, while pregnant.

The kingdom being still in danger, and nothing having changed about the reasons for an alliance, the middle sister marries the same prince, as soon as is seemly. Marra is sent to a convent dedicated to Our Lady of Grackles, so as to forestall any possible countervailing alliance. Being used as a pawn, having no say in her future comes as a shock to Marra, who had heretofore quite liked the princess life. Even more shocking is when she discovers how the prince has been abusing her sister. He still needs her to produce a male heir, so he is careful not to damage her too much, but it is a horror nonetheless. Marra’s sense of helplessness increases.

In the meantime, she becomes friends with the Sister Apothecary, and Marra’s help with a patient who has a broken leg earns her praise that cannot be traced back to her standing as a princess. For an uncertain novice in her mid-teens, that’s a balm for the soul. In due course, she is called to help attend at a birth.

“You’ve seen one, haven’t you?” [said the Sister Apothecary].

“One…?” said Marra. “Only one.”

“Then you’re ahead of the Brother Infirmarian. He hasn’t touched that end of a woman since he slid out of one. My assistant’s down with the flux and I need someone to hold a lamp.”

Marra gulped. She waited to see what she would do next, half-convinced that she would curl up in a ball and whimper, but instead she straightened up and said, “All right. Let me get on my shoes.”

—

The labor went very much the same way that Kania’s [her surviving sister’s] had, which seemed strange to Marra. Then again, peasants and princesses all shit the same and have their courses the same, so I suppose it’s no surprise that babies all come out the same way, too. Having thus accidentally anticipated a few centuries’ worth of revolutionary political thought, Marra got down to the business of boiling water and making tea. (p. 49)

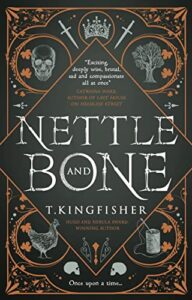

Nettle and Bone is a fantasy novel written mostly in the register of a fairy tale, or maybe a fairy tale spun out to the length of a fantasy novel. Details are only provided as the story requires — the name of the king is never mentioned, for example — and Kingfisher has not built a complete world to set this tale in. It holds together because the pieces of the story fit together, because the characters earn the distance that they travel, because any magical shortcuts come at a price. This approach also allows enables the occasional contemporary intrusion — “centuries of revolutionary political thought” — to add levity, rather than breaking the spell entirely.

The book needs levity, because Marra has determined to rescue her sister by killing the prince. She hears of a grave witch, a dust-wife, far away to the south who might know a way. Sister Apothecary helps her sneak out of the convent, and the sequences of her travels, how she learns to be a nun in the world, is a lovely bit of storytelling, vivid and economical, by turns tense, funny, and fascinating. The dust-wife sets her three impossible tasks, the first of which is to make a cloak of owlcloth and spun nettles. The second is to make a dog of bones, which is how she gets to the novel’s first scene. Not quite a third of the way through, that circle is closed.

“God’s balls,” said the dust-wife a week later, looking at the bone dog. “You did it.” She did not sound happy about it. She hadn’t sounded happy about the cloak of nettles, either, when Marra had come down with her ruined hands and her swollen lips and dropped the owlcloth garment at her feet.

“I did,” said Marra. “Where do I begin the next task? Moonlight in a jar of clay?”

The dust-wife groaned. She got up without answering and went to rummage in her pantry. Eventually she found a pile of chicken bones and tossed them to the bone dog.

Marra had a vague notion that chicken bones were bad for dogs, but she also wasn’t sure that there was anything in the bone dog to be injured. He lay down happily and began to gnaw. Bits of splintered bone rained out of his neck as he swallowed.

The dust-wife pulled out a chair at the table and slumped into it. She was tall and bony and stoop shouldered where Marra was short and round. “Do you know why you set someone an impossible task?” she asked. Marra scowled. This was the sort of question that she hated, the kind that made her think that the other person was trying to be clever at her expense. But the dust-wife had dealt fairly with her, so she tried to think of an answer. “To see if they can do it?” She racked her brain, thinking of all the old legends. … “To see if they are heroes?”

“Heroes,” said the dust-wife with an explosive snort. “The gods save us all from heroes.” She gazed at Marra, her normally expressionless face lined with sorrow. “But perhaps that’s the fate in store for you after all. No, child, you give someone an impossible task so that they won’t be able to do it.”

Mara examined this statement carefully from all directions. “But I did it,” she said. “Twice.”

“I had noticed,” said the dust-wife grimly. “And quite likely you will do the third task and then I will be obliged to help you kill your prince.”

“He isn’t my prince,” said Marra acidly.

“If you plan to kill him, he is. Your victim. Your prince. All the same. You sink a knife in someone’s guts, you’re bound to them in that moment. Watch a murderer go through the world and you’ll see all his victims trailing behind him on black cords, shades of ghosts waiting for their chance.” She drummed her nails on the table. “You sure you want that?” (pp. 95–96)

Marra does. The third task throws Marra as much for a loop as the other two. The dust-wife passes her a jar and tells Marra to open it. She does and sees moonlight shining out.

“Close it again,” ordered the dust-wife. “There. The moon in a jar of clay. Give it back to me, please.”

Marra, by now thoroughly bewildered, closed it and passed it back to the dust-wife. …

“There,” said the dust-wife. “You have given me moonlight in a jar of clay. Well done. That’s the third task.”

“But…” marra stared at her and the little clay jar with the moonlight inside. “But I didn’t earn it. I didn’t do anything.”

“It was an impossible task,” said the dust-wife. “The other two should have been impossible, but here you are with a bone dog and a cloak made of owlcloth and nettles. Catching the moon would have broken you, though. That’s not a task for mortals who want to keep their hearts.”

“But…”

“I didn’t want to do this,” said the dust-wife. “That’s why I gave you the impossible tasks, so you’d fail and go away and not ask any more. I don’t like travel and I don’t like going places and I’m going to have to find someone to watch the chickens. And also this is a fool’s errand and we’ll probably all die.”

“But…?” A hope began to bloom in Marra’s heart. She fought it down, telling herself that she must be mistaken.

The dust-wife shook her head. “You want a weapon against a prince. Well, I haven’t got a magic sword or an enchanted arrow or anything nicely portable.” She leaned back in her chair. “So. Your weapon against the prince. That’s me” (pp. 98–98)

Impossible tasks and incongruous pairs are the stuff of the rest of the book, though the first third had no shortage of either. The dust-wife isn’t kidding about the demon. They gather more help at a goblin market, though there is a price to be paid. Carelessness getting in and out of the market might have made the price far higher, but the dust-wife is there with wisdom and unwillingness to put up with nonsense, even from the dead. The story would be incomplete without godmothers to bless births, especially royal ones, but the way they work in this fairy tale is just a little different from elsewhere.

Once Kingfisher has united the story’s past and present, the pace never slackens. Great and terrible deeds follow, along with ancient mysteries and perfectly timed comic asides. And almost everyone lives happily ever after.

1 ping

[…] help each other, and so naturally things start to go awry. It’s unfair to say that I liked Nettle & Bone, the other Kingfisher story I’ve read recently, better — one has the full space of a novel […]