Good characters keep revealing more of themselves over time. Mr J.L.B. Matekoni has been around the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency for quite a long while, first as the owner of the garage next to the agency, and then as husband to Precious Ramotswe, father to their adopted children. He is a steady, low-key man, slightly old-fashioned in his preferences, especially when it comes to automobiles, but willing to follow good sense and adapt. He is a whiz with mechanical items, and better than one might think with people, especially in his management of the two long-time apprentices in the garage. A few volumes back, he had a bout of depression, and since then Mma Ramotswe has kept an eye out for its potential return. A few days after he went to a course organized by the local Chamber of Commerce — titled Where Is Your Business Going? — she is worried that he might be having another episode. He does not seem himself. She brings up Mr J.L.B. Matekoni’s changes in a conversation with Mma Potokwani, the formidable matron of a local farm for orphans.

“Well, he seemed to be in a very quiet mood last night. And again this morning, when I made him his breakfast, he ate it without saying anything very much. He usually talks to me in the kitchen while I am making breakfast for everybody. He talks to the children. He talks back at the radio. But no, he said nothing, and just looked out of the window, as if he was thinking about something,” [said Mma Ramotswe].

“Sometimes they do that,” said Mma Potokwani. “Sometimes men think.”

“I know that,” agreed Mma Ramotswe. “There are many men who think, Mma.”

Mma Potokwani looked thoughtful — as if she were weighing the truth or falsity of what had just been said. (p. 44)

They consider the matter a while longer, and eventually Mma Potokwani tactfully broaches the question of whether Mr J.L.B. might have met someone while on the course. It seems unlikely, but Mma Ramotswe has been a private detective long enough to at least contemplate the idea. They dismiss the possibility, but Mma Potokwani suggests that something else may have happened. “He might have been somehow persuaded that he is a failure. Or he might have met all sorts of big, successful people there and drawn the conclusion that his own business was never going anywhere. He might well have been upset by that.” (p. 45)

The puzzling state of Mr J.L.B. Matekoni is not the only troubling matter that comes out in the course of that visit to the orphan farm. One of the house mothers has a new girl of thirteen who had been brought to the farm after being treated in town for a broken wrist. After the charity treatment, the doctors asked her where her home was. She said that she did not know, that she had been working for a family but that she did not want to go back. She was frightened. And so she was taken to the orphan farm. It transpires that she had been working for a wealthy and well-known family, who had treated her cruelly. Worse, this family had in the past given money to the farm, and so Mma Potokwani feels that she is in a bad position. The house mother would like Mma Ramotswe to investigate and see whether some justice can be had for the girl, and for others who are still working for this family without being paid.

Finally, a client comes to the agency seeking help in a family matter. The client’s aging father is well-to-do, but has recently changed his will to leave a fine house and some land to the nurse and housekeeper who has looked after him in recent years. The client suspects untoward influence over a man whose mental faculties are not what they once were.

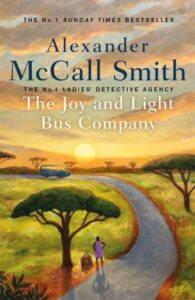

The Joy and Light Bus Company, the twenty-second book in the series, strikes a good balance between stories that arise from the nature of the characters and cases that come to the agency, whether in the expected business fashion as with the client inquiring about his father’s testament, or through other (unfortunately less remunerative) channels, like the question of the wealthy family’s exploitation of their workers. Another nice aspect of the book is how McCall Smith shows that the agency has a small measure of fame in Gaborone. Her little white van is sometimes recognized; at other times, she is known to be “that lady with that detective agency.” A reputation can be useful to Mma Ramotswe in her work, but being known can also complicate the anonymity that helps her to discover relevant facts without the subjects of her investigations realizing what she is up to. It’s good to see McCall Smith considering how his characters have effects outside their own circles.

It soon transpires that Mr J.L.B. Matekoni did in fact meet someone while on the course: a successful businessman he had known when they were both schoolboys. Mma Potokwani was right when she said that he had compared his business unfavorably to his old friend’s, and that this had made him sad. What she didn’t expect was that the friend, Mr T.K. Molefi “this holder of an MBA degree, this successful entrepreneur who had even written a forthcoming book” (p. 34), would invite Mr J.L.B. Matekoni to join in on a new business venture: the Joy and Light Bus Company. All it would take is some starting capital, raised by taking out a mortgage on the business including both the garage and the building that houses the detective agency. The bus business is also highly competitive; the planned company will start with just one bus; and it’s not clear from the description whether Mr T.K. Molefi is investing much at all for his part. Mma Ramotswe is appalled, and yet she sees how much the venture means to her husband. Is he just a mechanic with a garage, or is he a businessman?

The rest of the book is about untangling these three threads, with characters who are true to themselves and yet showing new facets, even after more than twenty books. I was tickled to think of the initials of Joy and Light Bus, in relation to their potential investor. The book is also about acceptance, at least for Mma Ramotswe: acceptance that persuading her husband not to make a mistake might be worse for him than the mistake itself, acceptance that she might be wrong about the bus company, acceptance that her client might not be the honorable actor in a case, that her friend might have had her judgment clouded by wealthy donors. It all comes right in the end, because with a title like Joy and Light, how could it be otherwise?