With Marzahn Mon Amour Katja Oskamp aims for a double re-evaluation: of her own writing, seemingly derailed after two novels and a story collection are followed by publishers’ rejections of the novellas that followed, and of the district of Marzahn in the northeastern corner of Berlin, far from the city’s hip party places or its political center. Along with the apparent end of her literary career, at age 44 she was facing other common crises of middle age — her child was moving out, her husband was seriously ill — plus the social invisibility that many women report experiencing as they age. “Ich tauchte ab,” she writes at the end of the book’s second paragraph. “I dove down,” most directly, but it carries connotations of disappearing, of choosing to leave things behind, of cutting communications.

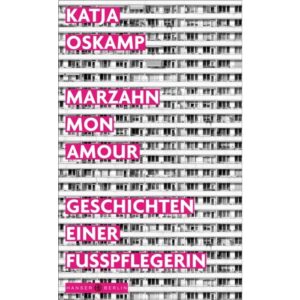

She dives into a new profession — foot care specialist — and through a social connection she sets up practice in an unloved quarter of Berlin, Marzahn. The tram that she takes to her new job, the M6, begins in the center near the city’s cathedral and the famed art and archeology exhibits of Museum Island. The M6 wends its way slowly northward and eastward through Alexanderplatz and the nearby parts of East Berlin that have become fashionable since reunification out toward the high-rise blocks built by the communist regime to house vast numbers of Berliners. Marzahn, as Oskamp relates, began as a village, and its old core can still be found among the accumulation of later eras. And while a brief look on Google Maps will show that the district has large swathes of low-rise housing, the pre-fab high-rises from the late 1970s and early 1980s undoubtedly shape its image. Oskamp’s book plays on this as well, with a cover photo that shows balcony after almost identical balcony of an anonymous tower block.

On the ground floor of one of those blocks, Oskamp takes up work in a cosmetics salon. She’s the foot specialist; the owner does beauty and makeup; Flocke, the other colleague, does nails. The German word for Oskamp’s role, Fusspflegerin, is sometimes translated as podiatrist, but that title usually implies a medical degree, which Oskamp does not have. She’s more of a practical care specialist, doing hands-on care, and more importantly she’s someone who has more time for patients than doctors do. She talks with them, judges their moods and what they need, practicing psychology as much as providing physical care. The word appears in the book’s subtitle as well, Geschichten einer Fusspflegerin. A Foot Care Specialist’s Stories, but whether they are stories that the specialist tells or stories of the specialist is left open, because of course they are both.

In Marzahn Mon Amour Oskamp provides 17 portraits of customers she comes to know over the years from 2015 to 2019 when she was exercising her new profession and collecting tales of the people who came to her studio. There are a few other sections, including an introduction and a conclusion when she writes more directly about her life, and what she has come to think as a result of her work in Marzahn. Part of her mission with the book is to give visibility to the kinds of people who are not often written about in contemporary German literature. They live in an unfashionable part of the city, they are mostly older, they do not have much in the way of power or glamour in their lives. Oskamp wants to write about them anyway, to assert the value of the ordinary.

They’re good and convincing portraits, on the whole. After more than 20 years in Germany and coming up on a dozen in Berlin, I could recognize the type of person and the contours of many of the biographies. Given her line of work, most of her clients are older, and the collapse of the communist system played a role in their adult lives. Marzahn, Oskamp relates, has the reputation of being home to many functionaries of the old regime, a place where gray men lived in gray retirement. Not true, she says, and her stories also show how individuality inevitably continued under a system dedicated (notionally at least) to the collective. She does portray one former Party man, a certain Herr Pietsch. Turns out he’s a sex pest. Struggles with alcohol appear in many back stories, and one person, with particularly appalling feet, appears in the company of two social workers who are slowly nudging him back toward functionality. He’d drunk away the decades since he was a teenager, he says, not without a certain pride.

Most of her clients are women, though. The oldest is 96 and comes with her bossy daughter, herself in retirement age. The youngest appears in a chapter titled “Adolescent Daughters of Women Writers,” in which some of Oskamp’s acquaintances from the literary world send their teenage daughters out to Marzahn for some professional help in overcoming body image issues (“My feet are so weird!”), or maybe just some real talk that isn’t from their moms. Frau Guse is a hilarious character whose mobility was limited by the polio she caught as an infant in 1955, but whose life wasn’t. Frau Janusch took care of husband and daughter, and now as a widow — “Keen Mitleid!” “No sympathy!” in the Berlin dialect Oskamp skillfully captures throughout the book — she is figuring out what to take care of now.

There is not an overarching story in the portraits and the interstitial bits, but there is an art to their presentation. The early ones introduce the work and the common themes, such as how people visiting for the first time typically apologize for something about their feet. Later on, they go into greater depth about personal histories. Oskamp closes with observations about writing and care work, along with brief follow-ups on many of the people previously described. She writes that in the period the book covers, she had seen roughly 1900 people. Readers are left on their own to surmise how and why she chose to write about the people she did. One thing that struck me about her selection is that there’s practically nobody of non-German extraction. The only one I can recall is an unnamed Russian woman who commits suicide by jumping from a high-rise near the studio. Oskamp and her colleagues hear the impact, but do not immediately understand the import of the sound. A lesbian couple that the studio crew knows saw everything while walking their dogs; they tell Oskamp and her colleagues to call an ambulance, but there is nothing to be done.

Another aspect of her selection is that those years saw a surge of a million or more refugees into Germany, and she says that the share of refugees who live in the district is high. Yet the refugee story that she chooses to tell is that of Gerlinde Bonkat, who fled, along with her mother and brother, as a child from East Prussia in January 1945. Bonkat’s story is interesting, and affecting. The family were visibly practicing Christians in atheist East Germany; Bonkat’s mother tells her that she can forget about advanced education because of their beliefs. (Why didn’t the family head further west between 1945 and the construction of the Wall in 1961? Oskamp doesn’t say, she doesn’t indicate that she ever asked.) Nevertheless, Bonkat eventually gains training as a nurse, and she seems truly to have had a caring vocation. Oskamp describes her as something of a secularized nun, someone who had few material interests and was always interested in helping others. Of all the refugee stories that Oskamp could have chosen — and she only chooses one — why the one that says “Germans suffered because of the war too, you know”?