Vasily Grossman is one of the great writers of the twentieth century, and The Road is a very good place to start reading his work. Born in the Ukrainian city of Berdychiv when it was part of the Russian Empire, Grossman experienced the Bolshevik Revolution and the ensuing civil war as a teen. He began writing short stories while studying chemical engineering at Moscow State University, and one of his early stories drew favorable notice from influential Soviet writers Maxim Gorky and Mikhail Bulgakov. He worked for a time in Donetsk, back when it was called Stalino, but by the mid-1930s he was both living in Moscow and able to write full-time.

He came into his own as a writer when he worked as a war correspondent for the Red Army newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star). Grossman witnessed and wrote about the Battle of Stalingrad, the great tank battle at Kursk, and the Soviet campaign to capture Berlin. In Stalingrad, he spent more than three months on the right bank of the Volga (p. 66), where house-to-house fighting between the Red Army and the Wehrmacht raged and the war in Europe was decided. He was one of the first reporters to see the Nazi extermination camp at Treblinka, which he reached in July 1944. Many of his dispatches are collected in A Writer at War, which is probably the other good place to start reading Grossman, as his best-known novels, Stalingrad and Life and Fate are vast epics.

After the war, Grossman increasingly came into conflict with the Soviet state. His work reporting Nazi crimes against Jews was suppressed, and he himself was fortunate to escape the anti-semitic campaign of the early 1950s, which only ebbed because of Stalin’s death. The cultural thaw of the Khrushchev years had its limits, as Grossman discovered when he submitted the manuscript of Life and Fate for publication. The authorities not only refused publication, they confiscated every copy of the manuscript that they could find, going so far as to take the typewriter ribbons that Grossman had used to write the novel. Only Solzhenitsyn’s work was as thoroughly repressed. Grossman died of cancer in 1964 at the age of 58. Life and Fate was not published until 1980; it was not published in Russia until 1988.

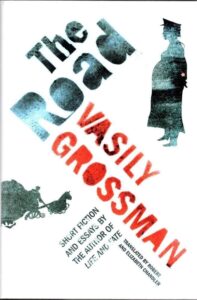

The Road, which was translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler with Olga Mukovnikova, provides an overview of Grossman’s writing career. Its 17 stories, articles and letters are arranged chronologically, organized into five parts. The editors and translators also provide a considerable amount of useful supplemental material. Each section has an introduction that gives details about Grossman’s life, the historical and literary contexts, and specific commentary on the works selected. There are also footnotes within the texts that give helpful information, particularly for the article about Treblinka where subsequent research has confirmed almost all of what Grossman reported but has also revealed some errors. There are two appendices — one about Treblinka and one that fills in background of the story “Mama” by describing the relationship between a Stalin-era head of the secret police and the child he adopted, as well as her life after his execution — plus an afterword by one of Grossman’s adopted sons. This last is an intimate glimpse into the writer’s life and times. The additional material in The Road will deepen a reader’s understanding of Grossman’s stories, and though they are strong enough to stand on their own, the extra context reveals further layers of his art.

The stories from the 1930s follow the accepted style of the period, but even there Grossman delivers the unexpected, with characters who don’t quite fit the mold and keen observations that breathe life into stock situations. Part two, “The War, the Shoah” shows not only Grossman’s growth as a writer but delivers utterly bone-chilling tales of life under Nazi occupation. Then there’s “The Hell of Treblinka.” As noted above, Grossman was part of the Red Army, and arrived in the isolated corner of Poland that housed the extermination camp of Treblinka just weeks after the Nazis left. He was able to interview some of the former worker-inmates who had escaped and survived. He was also able to interview local residents who had lived nearby throughout the camp’s construction, operation, and eventual abandonment. From these interviews and other investigations he was able to reconstruct the process of murdering humans on an industrial scale. He was able to identify some of the specific perpetrators, and to construct a chronology of the camp’s rise and operation. The article was rapidly translated into numerous languages, and it was entered into evidence at the Nuremberg trials of major war criminals. Grossman apparently had a bit of a breakdown after writing this article. As well he might. It is a hard but essential piece of writing. The editors choose to follow “The Hell of Treblinka” with “The Sistine Madonna,” a meditation on the sublime and immortality, on life and the very best that humanity has to offer.

The final three parts — “Late Stories,” “Three Letters,” and “Eternal Rest” — draw from Grossman’s postwar career. These were the years of his great novels, and his great struggles to get them published in a form that the censors would allow and that he could accept. With Stalingrad, then called For a Just Cause, he succeeded, though the authorities demanded many changes. Life and Fate was too hot for Soviet publishers to even consider. Some of the late stories are wonderfully strange: “The Road” is a World War II story, told from the point of an Italian mule who is first drafted into pulling carts in Abyssinia and then later across the Ukrainian steppe. He finds fulfillment after getting captured by the Soviets. Others are as sobering as the wartime tales, delivered with craft that Grossman had more finely honed in the intervening years. The letters include two that he wrote to his beloved mother on anniversaries of her execution by the Nazis in occupied Ukraine, a fate that he thought that he should have been able to prevent by working harder to bring her to Moscow sooner, a guilt that never left him. Concerning the last part, the editors write “‘Eternal Rest’ is a meditation on cemeteries and on the relationship between the living and the dead. Much of the first part is about the battles people often have to fight in order to arrange for a loved one to be buried in a particular cemetery.” (p. 297) It illustrates some of the customs that Catherine Merridale explicated in Night of Stone, with the humor and empathy that are Grossman trademarks.

Grossman’s road was one of the hardest of any writer in the twentieth century. The Road delivers an introduction to the great art that he brought back, the humanity that he never lost.

1 pings

[…] bit more widely among languages than in recent years. The most common pair was Russian to English (The Road, Metro 2033, An Armenian Sketchbook, The Helmet of Horror), and those were disparate in their […]