World War II in Europe began when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in the early days of September 1, 1939. Sixteen days later, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east. Less than three weeks later, the Nazis and the Soviets had conquered all of Poland. They divided the country between them according to the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Jozef Czapski (pron. “Chop-ski”) was over 40 when this war came; he had previously served in World War I, been a pacifist for a time, thought better of it and fought against Soviet Russia when it invaded Poland in 1920. Between the wars, he had lived in Paris and pursued painting, his true passion.

Czapski did not discover Proust until 1924, after the writer’s death, and he did not take to the writing right away.

I was too little acquainted with the French language to savor the essence of this book, to appreciate its rare form. I was more used to books where something actually happens, where the action develops more nimbly and is told in a rather more up-to-date style. I didn’t have sufficient literary culture to deal with these volumes, so mannered and exuberant … Proust’s lengthy sentences, with their endless asides, myriad, remote, and unexpected associations, their strange manner of treating entangled themes without any kind of hierarchy—the value of this style, with its extreme precision and richness, seemed beyond me. (p. 12)

One would think that picking up, by chance, the next-to-last volume of À la recherche du temps perdu would be the way to ensure estrangement for good, but no. “[A]ll of a sudden [I] read from the first to the last page with increasing wonder.” (p. 12) That wonderment spurred Czapski’s interest in the rest, and by 1928 he was already contributing to the secondary literature. Eric Karpeles, the translator of Czapski’s lectures, writes that he was one of the few Poles at that time who had read the whole novel in French. He had also read most of Proust’s correspondence that had been published by then, as well as numerous commentaries including one that apparently stayed so strongly in Czapski’s memory that a passage from it forms the conclusion of his last lecture.

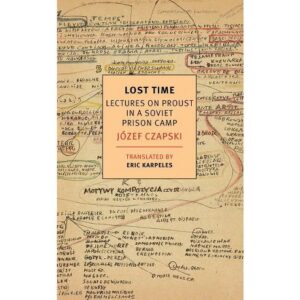

Because the thing about the five lectures that comprise the main text of Lost Time is that Czapski composed them entirely from memory.

He was captured by the Soviets, and taken to a series of prisoner-of-war camps. First to Starobielsk, near present-day Kharkiv from October 1939 to the spring of 1940. “There we tried to take up a kind of intellectual work that would help us overcome our depression and anguish, and to protect our brains from the rust of inactivity.” (p. 5) In April 1940, the camp was emptied, as were two others at Kozelsk and Ostashkov; the prisoners were deported northward. Czapski’s introduction to the lectures, written in 1944, tells what he knew at the time:

… numbering in all about fifteen thousand people. Of all these prisoners, the only ones ever to be seen again were about four hundred officers and soldiers grouped together at Gryazovets, near Vologda, during the year 1940–41. We were seventy-nine out of four thousand from Starobielsk. All our other comrades from Starobielsk disappeared without a trace. (p. 6)

Later, Czapski was assigned the task of finding out what happened to these men. He tells some of the story of this search in Inhuman Land, his memoir of what happened after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union transformed Poles from enemies to allies, and the Polish prisoners were released to form a new army. He did not find out during the war, for the fate of the thousands of Polish officers was one of the Soviets’ deepest secrets: they were all shot on Stalin’s orders. The Soviets blamed the Germans, and did not admit the truth until the Gorbachev era some forty years later. Czapski was a rare survivor, though he had no idea when he put together the lectures that became Lost Time.

In Gryazovets, much bargaining with the camp authorities secured permission for the prisoners to present lectures to each other. “I can still see my companions, worn out after having worked outdoors in temperatures dropping as low as minus forty-five degrees … listening intently to lectures on themes very far removed from the reality we faced at that time.” (p. 7) The range of topics gives something of an idea of the caliber of the Polish officer corps:

The history of books was recounted with rare feeling by a passionate bibliophile from Lwów, Dr. Ehrlich; the history of England, the history of the migrations of peoples, formed the basis of lectures given by Father Kamil Kantak from Pinsk, former editor of a daily newspaper in Gdansk … Professor Siennicki from the Polytechnic School at Warsaw spoke about architectural history; Lieutenant Ostrowski, author of an excellent book on mountain climbing, who had made numerous ascents in the Tatras Mountains, in the Caucasus, and the Cordilleras, spoke to us about South America. (p. 6)

Czapski spoke about French and Polish painting, as well as French literature. At the camp he had an indoor job, and thus better conditions to prepare his presentations. What he did not have were any sources at all. No Proust, no commentary, only what he himself could recall. Proust’s great work on memory, described entirely from memory.

The existence of the lectures is extraordinary enough, but they are learnéd, lively, intriguing, inviting. Of course it helped that Czapski knew some of the principals personally. In a discourse on Proust’s style, the conflicts he had with French arbiters of taste, and Proust’s assertions that his sentences were more Latinate and thus truer to the French language than the reigning brevity that descended from the Encyclopedists, Czapski veers into a discussion of Proust’s first major translation into Polish.

On account of this I had a talk with [Tadeusz] Boy-[Zelenski] in which he defended his position, claiming that he didn’t set out from a position of working against Proust but for him; it was always his intention to clarify the Proustian text. Boy knew Proust wanted to be a popular success. It’s wrong to sanctify a writer—one has to edit him in a manner that makes him most readable. Anyway, Proust had consented to alter his original idea of a single volume in France. When it came to a Polish version, Boy insisted, Proust’s extended sentences were unacceptable, beyond the means of the Polish language … “I sacrificed the precious for the sake of the essential,” he declared. The immediate result was that suddenly Proust read very easily. From the moment his Polish translation appeared, people in Warsaw loved to repeat the joke that the French should just translate Proust back into French from the Polish translation; then at last he would become hugely popular in France. (pp. 32–33)

Czapski roams among setting, Proust’s biography, the interplay of different art forms. He takes in French literature and ties it to the Polish literature that his listeners would have known. He examines Proust’s forms, his style, where he broke from tradition, and what made his vast novel extraordinary. He discusses how changing times — specifically before and after the Great War — affected Proust’s writing. He weaves in funny stories, as when Proust finally ventured out to a party, only to have his hostess think he had been uninterested because his back had been turned most of the evening, whereupon Proust recounted so many details that she realized he had been paying closest attention. Then Czapski turns these anecdotes so that they reveal further aspects of Proust’s work. Most of all, and like the other lecturers, he brings his comrades out of their captivity, if only for a little while, reminding them of a different life, of why they are fighting, and who they might once again be.

Czapski survived the war, and he lived long enough to see the end of communism in Poland. Born in 1896 to an aristocratic family in Habsburg Prague, he died at age 96 in a suburb to the northwest of Paris.

I’ve not yet read any Proust. If I ever do, Czapski will have shown me the way, and I hope I will feel at home.

2 pings

[…] Here is how I last introduced a book by Jozef Czapski: […]

[…] writing of Jozef Czapski persuaded me to read Proust, and the writing of Marcel Proust persuaded me to stop. Czapski noted […]