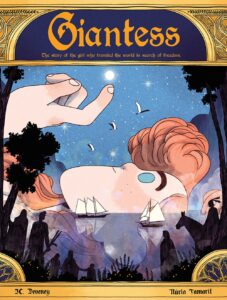

The Story of the Girl Who Traveled the World in Search of Freedom. Translated from the original French by Dan Christensen, with localization by Mike Kennedy.

This feminist fable follows the discovery a giant baby girl in a secluded mountain valley. The farmer who discovers her takes her in to be raised as the youngest child in a family that already consists of himself, his wife and their six sons. The farmer’s wife is thrilled to finally have a daughter and names her Celeste. Her six brothers, all with distinct personalities, grow just as fond of their sister as she does of them.

This feminist fable follows the discovery a giant baby girl in a secluded mountain valley. The farmer who discovers her takes her in to be raised as the youngest child in a family that already consists of himself, his wife and their six sons. The farmer’s wife is thrilled to finally have a daughter and names her Celeste. Her six brothers, all with distinct personalities, grow just as fond of their sister as she does of them.

So she’s devastated when the years pass and each boy grows up and leaves their isolated home. Her father refuses to even think of her leaving to explore the wider world beyond their farmstead, in large part out of fear of how she’ll be treated by the rest of humanity: not merely because she’s a giant, but also because she’s a girl. When she comes across a smooth-talking peddler, she’s thus easy prey for his con artist ways, and embarks with him on a journey that sees her enduring the worst of her father’s fears, but also attaining greater heights than anyone in her family had ever dreamed.

As a testament to the might and power inside every woman, this is an affecting metaphor about what women can do even in the face of terrible odds. But readers should go into this book knowing that it comes from a very old-fashioned Catholic European framework that can make certain narrative choices seem really odd for people without a similar background. In perhaps the first and most jarring example, Celeste gets her period and, instead of telling her concerned mother about it, decides it’s something shameful that she doesn’t want to talk about. To me, this is a strange response from a farm girl with zero external contact with the biases of society. It would have made more sense if there had been some sort of influencing behavior from her family, but the book doesn’t show that at all, assuming that readers will have the kind of background that will fill in the blanks that lead towards shame instead of a more matter-of-fact acceptance of biology.

It gets even weirder when Celeste at one point joins a convent. There’s also a heavy-handed bit about an island of man-hating “mermaids” (I suspect that “sirens” would have been a better translation) that felt more like an appeasement towards men scared of feminism than a solid story choice. Which is also weird, because Celeste’s brothers are really great allies throughout! A large part of me chafes at a genre that I perhaps ungraciously call Feminism For Dummies, even as I know that books and media like this are necessary tools to reach people (especially cis men) who might never even have thought about their own places in the patriarchy. Ah, well, at least it lets Celeste be the center of her own story, with a thoughtful ending that neatly sidesteps the idea that she has to fulfill particular roles in order to feel satisfied as a person.

Núria Tanarit’s cartoony art works well for the simple fable, with expressive lines and lovely detailing and color. I just had higher expectations of the story. It’s fine for what it is, and probably good reading for people still trying to figure out why the fight for equal rights continues to be necessary.

Giantess by J.C. Deveney & Núria Tanarit was published October 4 2022 by Magnetic Press and is available from all good booksellers, including