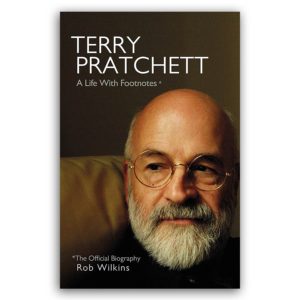

Terry Pratchett: A Life With Footnotes is something of a second-hand autobiography. Wilkins was Pratchett’s personal assistant from 2000 until Pratchett’s death in 2015 of a rare form of early-onset Alzheimer’s. He was also in possession of the notes toward an autobiography that Pratchett made but never turned into a full manuscript. As time went on, and particularly in the final years as Pratchett’s faculties diminished, Wilkins’ role increased: he read speeches that Pratchett had written; when Pratchett eventually took to social media, the Twitter account was @terryandrob. “Later on, Terry said to me, ‘It appears we now share a brain.'” (p. 11) So this is as close as readers will ever get to a Pratchett autobiography, and it is also a biography by someone as close to him as anyone who wasn’t family.

The truth is, I bounced right out of A Life With Footnotes the first time I sat down to read it and didn’t even make it through the introduction. Here’s what threw me:

I was also fired many times over, although one quickly learned that Terry, being a writer, had an experimental interest in saying things to see what they sounded like, and that if you adopted an experimental approach yourself, and simply turned up the next day, it would normally turn out that you hadn’t been fired at all. (p. 9)

I think that’s a rotten way to treat someone, let alone someone who works for you, let alone someone who’s meant to be your personal assistant. Immediately after that alarming report, Wilkins mentions Neil Gaiman’s introduction to a collection of Pratchett’s non-fiction in which he made a point of noting that Pratchett was not a jolly old elf. Pratchett had a deep well of anger — “This anger was the engine that powered Good Omens,” he told Gaiman — but it was anger in service of fairness and of decency. Fortunately, Pratchett had an expansive definition of who deserved fairness and decency: everyone.

He didn’t always live up to that himself. I don’t suppose anyone does, and it is to Wilkins’ credit as an honest biographer that he shows Pratchett’s irascible and capricious moments as well as the generosity and jollity of which he was equally capable. Thanks to that honesty, I have a much better sense of where Pratchett came from, where things I had dimly sensed in the Discworld books (I haven’t read his other fiction) linked in with his life and experiences. In the chapters describing Pratchett’s early life, Wilkins moves back and forth between the straightforwardly biographical bits and his recollections of Pratchett talking about his childhood, or illustrating one of the themes that Wilkins is developing in that section. He was not an early reader, but once The Wind in the Willows fired his imagination, there was no stopping him. The Lord of the Rings came along later, but was nearly as formative, and of course much closer to his eventual career. He was in his local library so much that the staff took him on as a junior librarian. That branch eventually bore a plaque dedicated to Pratchett, and his daughter related how much that would have meant to him: “Dad was born in Beaconsfield, but Terry Pratchett the author was born in Beaconsfield Library.” (p. 53)

In Wilkins’ description of the quietly formidable Granny Pratchett, I can’t help but see a lot of Granny Weatherwax. Except for the quiet part.

Wilkins details Pratchett’s early working years — and he started quite early, leaving school before finishing the final English qualifications and never attending university — first as a journalist and then in public relations for a nationalized utility. He brings these nearly lost worlds of regional weekly newspapers and big national industries back to life, showing some of the personalities that shaped Pratchett’s outlook, and some of the early friends he made and kept all his life. Between the lines it’s also possible to see someone who drove himself so hard that criticism from the outside — and one of the newspaper editors liked nothing more than to dish that out — was very hard to take for someone who was also as sensitive as Pratchett undoubtedly was.

Much of the book follows Pratchett’s writing career and his rise to dizzying heights of success. I found the ins and outs of publishing interesting. I previously worked in bookselling and specifically author events, so I especially enjoyed seeing how it all looked from an author’s point of view. Commenting on Pratchett’s approach to both touring and answering fan mail, Wilkins said that Pratchett had an almost superstitious view that his success depended in some way on his accessibility, or at least on the perception of his accessibility. Wilkins’ tone read as slightly skeptical to me, but I think Pratchett had the right of it. Certainly in the early years of Discworld his accessibility combined with his prodigious output to create a deep well of reader affection for both the books and the author himself. I’ve read elsewhere that in the early years of his career Stephen King would give an interview to basically anyone, and that continuous flow of items about the author — combined of course with a steady stream of books worth reading — kept him in peoples’ minds, which kept them buying books. Obscurity is the great enemy of published writers who aim for commercial success, and Pratchett’s accessibility plus his prodigious work ethic (and his publisher’s willingness to bring out multiple books in a year) contributed greatly to his sales.

Another great break that Pratchett got that Wilkins mentions, but to my mind underplays, was a radio adaptation of The Colour of Magic and, later, The Light Fantastic for Woman’s Hour, a mid-day show on BBC Radio 4. These adaptations brought Pratchett’s work to a much wider audience than he would have had as someone simply promoted as a fantasy author. For all that the British literary establishment looked down on Pratchett — and if they thought about him at all, they did, with notable exceptions such as A.S. Byatt — Discworld always drew from an audience much larger than self-selected fans of science fiction and fantasy. I think that these radio shows were a big part of how that got started. (Parenthetically, I agree with Pratchett that the first two books in the set are not the best place to begin with Discworld, even though that’s how I started. The first two are about that world. Starting with the third book, Equal Rites, Pratchett wrote stories about the people living on that world, and that made all the difference.)

Throughout the book, Wilkins has inserted stories from Pratchett’s later life, especially from the years after he received his diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s. The later chapters show how they coped with Pratchett’s increasing disability, how Pratchett turned his formidable energies — and by that time considerable public presence — to publicizing the disease and advocating for more research, and how remorselessly it progressed. Wilkins shows the good days along with the bad days, and how much some of the late-life honors meant to Pratchett. He is made a professor of writing at Trinity College Dublin, and his initial skepticism about teaching writing turns into lively classes that inevitably ran longer than planned and left him recharged about his vocation. After he was knighted in 2009, he forged the iron to make a sword.

He got a local blacksmith, Jake Keen, to join him on the project and help him with the smelting. Terry’s first words on meeting Jake were, “I’m told on good authority that you’re completely mad. Are you mad?”

Jake said, “Of course.”

“Good,” said Terry. “I like mad people.” (p. 371)

They added in some meteoric iron, lit the fire for the forge with friction rather than matches, and did the whole thing up proper. “When Hector [Cole, master swordsmith] showed him the finished item, Terry was visibly moved, holding it out and turning it in the light in wonder.” (p. 372)

As an honest biographer, Wilkins does not shy from how hard the last years and months and weeks and, finally, days were. Over time, they had adapted processes so that Pratchett could continue writing. Wilkins says that as long as he was writing he was living. Neil Gaiman has written that every Terry Pratchett book is a miracle, but Raising Steam and The Shepherd’s Crown are particular miracles, with a whole team working to help Pratchett keep doing the thing that most made him him.

In the epilogue Wilkins talks about Pratchett’s memorial. In his daughter’s words, “Had it been for someone else, and Dad had been attending, he would have wanted one just like it.” (p. 426) He talks about the unfinished projects that had been on the hard drive that Pratchett’s will instructed be crushed by a steamroller. He adds his belief that as long as a writer’s works are read, that writer — in Granny Weatherwax’s words that Wilkins does not use — “aten’t dead.”

2 comments

1 pings

I don’t remember either “The Colour of Magic” or “The Light Fantastic” on “Woman’s Hour”, but I do remember “Equal Rites”.

Author

Hope those are good memories! All I know is what I found in the text of the book.

[…] year’s Worldcon and a translation of a thousand-year-old poem, as well as two non-fiction books. Finalists took an even more expansive view of both “work” and “related.” […]