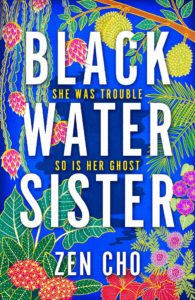

In contrast to Doreen, I do not feel perfectly suited to review Black Water Sister. I’m basically none of the things that the protagonist is, starting with Malaysian and ending with haunted by my maternal grandmother’s ghost. (To be clear, Doreen is not haunted by her grandmother’s ghost either. As far as I know.) None of that got in the way of enjoying the book. Once I got past a slightly shaky start, I started grabbing little snippets of time wherever I could to find out what happened next, through all the danger and reversals to the gripping, lovely ending.

Let me back up a moment, and borrow Doreen’s introductory summary of Black Water Sister. “Jessamyn Teoh grew up in America but moved back to Penang as an adult with her aging parents. Closeted and unemployed, she’s still trying to find her footing in an unfamiliar country where the weather alone can drain the unaccustomed into lassitude. Her girlfriend wants her to get a job in and move to Singapore where they can be together, but Jess is worried that her parents are too fragile for her to move that far away. The last thing Jess expects or needs is to suddenly start hearing a voice that claims to be the spirit of her recently deceased, estranged grandmother.”

This was the part of the book that I had trouble with. Jess doesn’t initially believe that what she’s hearing is her grandmother, Ah Ma, talking to her from a spirit world beyond death. My problem was that there wouldn’t be much of a book if Ah Ma turned out to be some sort of hallucination. Black Water Sister is not about the psychological tension between what is real and what is not; it’s not a story about how a person’s mind maybe plays tricks on them and gets them to experience things that aren’t real. The author knows that Ah Ma is real within the context of the story; readers coming to this book from Cho’s other fantastic stories are expecting a supernatural element of some sort; in short, everyone involved except Jess knows where this is going. So why does Cho spend fifty pages or so futzing about with something that’s a foregone conclusion? Yes, it’s important to Jess’ development that she comes to believe the evidence of her own senses and experiences, but I think the question of Ah Ma’s reality could have been dispensed with much more quickly.

Anyway, I am very glad that I persevered with the book because once Jess accepts that she has been caught up in a web of revenge and intrigue that goes back generations and crosses the line between the living and the dead, the human and the divine, the story is exciting and touching, and there’s no guarantee that Jess will find a positive way out of the web. Or any way at all. She may just be a young American, blundering into things she knows too little about, and paying the price. Because as much as her grandmother is pushy, economical with the truth, and willing to use Jess for her own ends, the Black Water Sister — a local god whose reputation is such that people are reluctant even to say her name — is much worse. And that’s not counting the ruthless businessmen and gangsters — is there a difference? — that Ah Ma and Jess manage to get crosswise with.

In answer to Doreen’s concern that readers with no knowledge of Malaysia might find the culture or language difficult to relate to or comprehend, I will say that I didn’t feel lost at all. I did take a while to figure out that Ah is not a name, but something like an honorific, and I am glad that Cho left that for readers to get on their own. Many characters speak a non-standard English. That made the dialog feel more grounded in its location, and I don’t recall ever struggling with the meaning; instead, I relished hearing their lively voices. Here are two examples more or less at random:

“I went for interview, thought it went well,” said Mom. “Then got phone call. They said they want a young person. They’re scared I cannot keep up.”

“Are they allowed to say that? That’s, like, age discrimination, isn’t it?” [said Jess].

“In Malaysia they don’t care one,” said Mom. “Last night I had to pretend to go to sleep early, otherwise I’ll sure tell Dad.” …

“Dad doesn’t expect you to get a job,” said Jess. “Don’t worry, Mom. We’re doing OK, right? Dad’s getting a regular paycheck, we’ve got somewhere to live…”

“Better if we have our own place. Not good for different families to stay in one house. Sooner or later they will fight.”

“Yeah, OK, but …”

“Chinese New Year coming soon some more.” (p. 122)

“You’re late already!” said Ah Ku. “My mother had to try to do by herself. Is it right you let an old lady do your dirty business?”

“Had to close shop first what,” said one of the men sullenly. He looked barely out of his teens, younger than Jess. …

The other guy was uncle-aged. Ah Ku’s reproof didn’t seem to bother him.

“Don’t need to answer back, Ah Tat,” he said to the boy. To Ah Ku he said, with the ease of long acquaintance. “It’s OK, what, we came in time. The business is not done yet also.” (p. 158)

I didn’t grow up reading Malaysian horror pulp adventures like Doreen did, but I relished Black Water Sister all the same.

2 comments

I’m glad you enjoyed the book, even if I disagree with your view on needing to dispense of the doubt of Ah Ma’s voice with alacrity. I felt it served to underscore how tenuous Jess felt in her own reality. Even as someone who values plot as much as I do, I think paring it down would have diminished the characterization. But different strokes, etc. Glad you could get to this one at all!

Author

“Glad you could get to this one at all!”

Me, too!