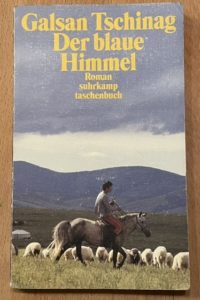

For some readers, Galsan Tschinag’s description of hard nomadic life in the Altai mountain region of Mongolia’s furthest western reaches in the 1950s will be enough. Der blaue Himmel — which could reasonably be translated as The Blue Sky or Blue Heaven — is a fictionalized memoir of a few years in a boy’s life, growing up in a family of shepherds in the Altai. As depicted in the book, it is a mostly self-contained, precarious, creaturely existence. Family members spend most of their time with the herds, and even the youngest have responsibilities as soon as they are able to fulfill them. By the time he is five or six, the narrator is looking after the small herd of sheep who cannot travel further afield — too young, too old, too lame, or temporarily incapacitated — to graze with the main flocks.

The family is not truly alone; in some seasons they keep their ger (Tschinag uses the word “yurt,” which seems still prevalent in German, while English was already trending toward the Mongolian term “ger” when I was there in 1999) near others from their extended family. The permanent settlement where the narrator will eventually follow his older siblings to school is less than a full day’s ride away. A medical emergency brings remedies from numerous sources, as word spreads among people willing to help. Nevertheless, Tschinag concentrates on a social world bounded by the narrator’s immediate family, most definitely including one dog (the family presumably has numerous dogs; this is so usual that a typical greeting as one approaches a ger is “Hold your dogs!”) that is very special to the narrator.

The narrator’s grandmother comes to live with the family after some sort of falling out with the sister she had been living with. Details are vague, as Tschinag tells the tale from a child’s perspective. The closeness between the narrator and the grandmother very likely reflects the author’s own history: The Blue Sky is dedicated to Tschniag’s grandmother, “the warming sun at the beginning of my life.” Grandmother has lost her teeth, so the child pre-chews meat for her, when they have it, and passes it to her in a form that she can consume. They also commonly use his fresh urine to treat an eye ailment she has.

It’s not all bodily functions, though. She tells him stories and makes time for him in a way that his parents, with all of their responsibilities to herds and household, cannot. He does not feel particularly poor, though any sweetener is a rarity, and bread is just a rumor, something somebody knew someone who once tried it. Bits of history — the coming of communism — impinge even in these far reaches of an extremely rural country. It emerges that an uncle, maybe a great-uncle, had been well off in the terms of the nomads. He had been known as a “bey,” a title that could have signified anything from a local notable to a regional leader. In a Mongolia that was under the Soviet thumb, that was a dangerously exposed position, and Tschinag does not say precisely what happened to the uncle. The older generation is clearly worried when the narrator says he wants to grow up to be a bey, telling him that they don’t use that word anymore. The communists are also replacing the traditional new year celebrations when winter starts to turn toward spring with January festivities and a winter figure that people who know Russian customs will recognize as Ded Moroz. The transition is not complete, but the new ways are clearly making inroads.

Time passes, so does the grandmother. Much of the second half of the book is taken up with the family’s struggle through a particularly harsh winter storm and the ensuing cold, known by the Mongolian word dzud. They work night and day to keep their herd from freezing, though they lose a noticeable portion of the flock. It’s a tense retelling of people versus an indifferent but deadly nature. Tschinag’s description makes it plain to readers how difficult and precarious nomadic life can be. For all that it can be beautiful, the people who live it do not romanticize it.