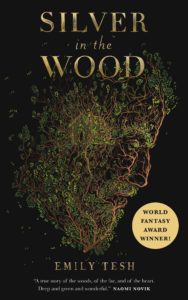

An unconsidered moment of kindness sets Silver in the Wood in motion. Tobias Finch had been in his cottage during an autumn downpour when he spied “a young man in a well-fitted grey coat stumbling along the track with wet leaves blowing into his face and his hat a crumpled ruin in his hands.” (p. 7) Tobias hollered for him to come in. Within the first three pages, Emily Tesh establishes differences between Tobias and his visitor, Henry Silver. Tobias’ cottage is neat and he keeps a cat, but the cottage’s one good window has cloudy panes, and when Henry arrives Tobias had been preparing to sharpen his own knives. Henry’s nice coat, by contrast, “was a damn good coat … the kind so perfectly tailored it required a servant to pour you into it and peel you out again.” (p. 8) The cat likes the visitor, and the two men seem inclined to pass the time in companionable silence, though they have only just met.

When they do start to talk, it’s the friendly sort of banter typically born of long acquaintance, though Tesh will later show that the conversation was hardly typical for either of them.

“They say a madman lives in Greenhollow Wood,” said Silver, looking over at him.

“Who’s they?” said Tobias.

“The people I spoke to in Hallerton village. They say there’s a wild man out here—a priest of the old gods, or a desperate criminal, or just an ordinary lunatic. He eats nothing but meat, raw, and it has made him grow to a giant’s stature; or so I was given to understand at the Fox and Feathers. They informed me that I would know him by his height and his hair.”

“His hair, hmm,” said Tobias.

“Waist-length and unwashed,” said Silver, looking at Tobias.

“Now that’s a slander,” said Tobias. “It’s not past my elbows, and I wash all over every week.”

“I’m glad to hear it, Mr Finch,” said Silver.

“The rest’s all true,” said Tobias.

“Old gods and banditry and lunacy?”

“And the one where I eat people,” said Tobias, unsmiling.

Silver laughed abruptly, a splendid peal of sound. “Maidens, they told me. Yellow-haired for preference.”

“Nothing for you to worry about, then,” said Tobias. (pp. 9–10)

Tobias reveals that he has figured out that Silver must be the new owner of Greenhallow Hall, making him Tobias’ landlord. When Silver asks how he can make it up to Tobias, he answers “Cut my rent.” They make a few more joking remarks about the wild man of the wood before Silver returns to the road to the Hall, bidding a friendly farewell.

With Silver gone, Tesh shows readers a bit more about Tobias, and his woods. Tobias goes to collect mistletoe, and “the old oak obliged him as usual” (p. 13). He goes to check “the old shrine. It was looking pretty ragged since they’d built the village church, but someone had left a handful of blackberries.” (p. 14) He eats them and goes to see where the woodsmen are working. Tobias accepts woodsmen as part of the forest’s life. “They’d set up a crossed circle of white stones facing east, casual-looking enough to fool a priest, but there wasn’t much power in it. More of a habit than a protection, these days. Still, Tobias appreciated the gesture. It made his work easier.” (p. 14) Tobias goes to the edge of the wood where it had been cut back around the Hall. Tesh writes that he can’t get any closer to the Hall, but he looks on and happily recalls Silver’s visit.

Having hinted about Tobias, Tesh shows him and his nature more fully in the next scene. A dryad has gone bad, and made her way to his wood. “Lost her tree, most likely, and no one had asked her mercy or planted her a sapling.” (p. 15) He takes up his station near the woodsmen’s cabin; Tobias knows they will be the target of her ire. She arrives after midnight, when she would have been strongest. “She was twisted and reddish, and her eyes lacked the sunlight-in-the-canopy gleam of a healthy dryad. ‘Now then, miss,’ Tobias said. ‘There’s no call for this.'” (p. 16) The confrontation that follows establishes Tobias’ power and place without saying much more about his nature.

Then things go wrong. “What could the woodsmen see, after all, but the wild man coming for them, and the hideous tangle of the dryad’s death throes?” (p. 19) In his hurt, Tobias makes for the source of his strength: home. The wood itself obliges. Brambles get out of the way, his cottage and the old oak are much closer to the edge of the wood than they usually are. Time has gone “slow around him, heavy and green after the way of the trees.” (p. 18)

Soon, Silver repays Tobias’ act of kindness by bringing him up to the Hall and nursing him through his convalescence. Astute readers will have noticed that Silver can find Tobias’ cottage, that he can bring Tobias out of the woods. Each of them knows more about the other than they say, as their banter continues and their entanglement gets thicker. Silver lets on that he can’t cut Tobias’ rent because he doesn’t pay any, that the last mention of the cottage in the Halls records is some four hundred years ago. He adds that he’s listed Tobias as his gamekeeper, as he could hardly tell his mother — who “somehow knows everything … and she writes the most horrible letters” (p. 27) — that he had paid for a doctor to tend the wild man of the woods. These pages were just a delight, and I wanted them to go on forever, or at least for the rest of the book.

Silver takes Tobias to see the old shrine one time and points out stains that indicate offerings are still being left, maybe some sort of blood sacrifice. “‘Or blackberry juice,’ said Tobias, hiding a smile. ‘Stains everything that does.’ Silver subsided. Nothing very exciting about blackberries, Tobias supposed.” (p. 43) Later, Silver is telling one of the woodsmen about the dangers of superstition:

“There’s a lot of interesting stories about Greenhollow Wood, I know,” said Silver. “But that’s all they are—folktales. There are no dryads, no wild men, no fairy kings, and no monsters. Isn’t that right, Mr Finch?”

“Certainly haven’t seen a fairy king yet,” said Tobias.

They days of banter and folklore don’t go on forever, of course. Things turn, like the seasons. Progress of the 19th century sort intrudes even on the deep slumber of a place like Greenhollow and its surrounding villages. But in such a place the turn of the seasons may be stronger than the march of progress. Tobias and Silver both have more depths than they have revealed to each other, and more bend than might be expected from an old tree. What happens next is a tale of revelations and transformation. Looking back, it seems as inevitable as a solstice, as surprising as spring, as satisfying as a hard task well-acquitted.

2 pings

[…] vein. T. Kingfisher’s A Wizard’s Guide to Defensive Baking and Emily Tesh’s Silver in the Wood spring to mind, though both have darker, deeper undercurrents than Legends & Lattes. I’m […]

[…] This review inevitably has spoilers for Silver in the Wood. […]