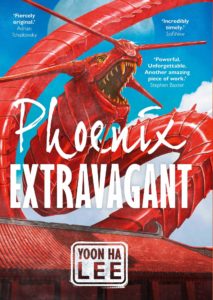

In Phoenix Extravagant, Yoon Ha Lee transposes the colonial history of Japanese rule in Korea to the Empire of Razan’s conquest of Hwaguk six years before the book’s beginning. Lee uses the framework to tell a story of an artist getting caught up in politics and history, only to discover they had been in it all along, even when all they wanted to do was paint.

Along the way, he considers questions of resisting, existing under occupation, collaboration, and people who have no choice but to be a part of both worlds. He sketches what artists do in a time of war, what they do to survive, and what they do when one side or another enlists them in their cause. Lee also examines the mixed results of a conquest that brings change and progress with it, how even those most determined to resist the new overlords cannot help but adapt some of their styles and methods. Lee touches on how conquerors can fear distant powers and see themselves as victims, or potential victims, acting in self-defense, a fractal spiral of justifications.

Lee chooses to tell the story from the perspective of Gyen Jebi — the personal name is Jebi — a nonbinary artist in their mid-20s. They start the novel taking an examination in hopes of gaining a position working for the Ministry of Art. It would mean working for the occupiers, but even before the invasion an artist’s life was precarious, and since then commissions have dried up and patrons gotten scarce. They sign their examination work Tesserao Tsennan, a Razanei name they had taken some time earlier for convenience, a hedge against bureaucracy and possibly a stepping stone in the new rulers’ garden. They hadn’t told their sister Bongsunga about it, though, for fear she wouldn’t approve. The two of them are orphans, and Jebi’s older sibling basically raised them, nurtured their art, protected them from some of the harsher aspects of the occupation.

Jebi gets in deeper when he is not offered a job with the Ministry of Art, but instead with the Ministry of Armor — the occupiers’ military arm — and it is an offer they cannot refuse. They learn the secrets of the Razanei automatons, robots that have no issue with harming humans or allowing humans to come to harm. They learn the horrible method used to create the magic pigments that power the automatons. Then they learn that the Ministry of Armor does not plan to be content with humanoid automatons and has built a dragon, though the Ministry has not yet bent its power to official will. Part of Jebi’s task is to paint the sigils that will ensure the Ministry will control the dragon.

In short, by the time Jebi has realized the situation they are in, they are in far too deep to get out on their own. They find unexpected allies. There is an improbable but charming romance. They try to get out of the Ministry’s clutches, and things only get more complicated.

I liked how different Phoenix Extravagant was from Lee‘s Machineries of Empire series. Where that felt very angular and mathematical, Phoenix Extravagant is all smooth brush strokes and ink bleeding into the handmade paper. Jebi reminds me, oddly, of Sibling Dex from A Psalm for the Wild-Built. It’s less that both are nonbinary and more that Jebi is the last to figure things out about people around them. They are caught up in their own things and oblivious to others in a way that’s sometimes endearing, sometimes exasperating, and always sincere.

Although Lee’s historical model was transparent to me, I liked seeing a slightly different model of conquest, and a deeper exploration of how people could come to support foreign rule. The rebels may be plucky, but they may also be on a fool’s errand: fighting against superior technology almost always guarantees a loss. I also liked seeing how advancing technology intrudes on a low-tech fantasy setting, largely as a side effect of human actions. And the ending is suitably fantastical.