Events at the end of Black City left Erast Fandorin, the Sherlock Holmes of Tsarist Russia, in a coma. The beginning of Not Saying Goodbye reveals that he has been in that state for a bit more than three years. Masa, his faithful companion for more than a quarter of a century, has watched over him the entire time. Fandorin’s swallowing reflex has remained active, so he has not been in danger of starvation, but the state between life and death has left Masa in a quandry about the right course of action. Medical advice eventually led him to a Chinese healer in Samara, a city on the Volga. Three months in Samara with treatments of acupuncture and herbs had enabled Fandorin to regain some weight and produced the first stirrings of consciousness. Unfortunately, just in those months the long-expected revolution in Russia broke out, disrupting everything, most especially Fandorin’s treatments.

That leads to the first farcical scene in Not Saying Goodbye, with Masa transporting Fandorin in a chaotic train trip as a large piece of upright baggage. This section is a spoof of train mysteries, with robbers appearing, and a sudden stop tossing their traveling compartment about, thus providing cover for someone within the compartment to engage in a little quick theft, too. Accusations fly until a loud noise near his ear returns Fandorin to consciousness, if not entirely to reason. He solves the mystery, though he regards his surroundings as a dream. He the promptly returns to a deep sleep that lasts days.

Eventually, though, the detective awakens fully; it would be a very odd Fandorin book otherwise. Masa brings him up to date on what has happened since August 1914: their whole world has fallen apart. In the first parts of the novel, he is still recovering his strength and reflexes. As Fandorin struggles to find his feet in revolutionary Moscow, Akunin deprives him of some of the spectacular abilities that had saved him from many scrapes in the past.

After the introductory farce, Not Saying Goodbye is divided into four parts, each exposing Fandorin and Masa to one of the major factions of the developing Russian Civil War. Their overarching goal is to depart from Russia by one of the southern routes. Fandorin recognizes that the Russia he knew and valued is gone. His time has passed, and he is willing to go to Japan with Masa so that they may live in Masa’s country as many years as they lived in Fandorin’s. Fandorin may not be interested in the Civil War, but to paraphrase Trotsky, the war is interested in him.

Each of the four sections is named for the color associated with a particular movement. The first, “The Black Truth,” begins with a street robbery that Fandorin observes and resolves to sort out, despite the continuing weakness that has him largely confined to a wheelchair. The trail leads him into an anarchist stronghold. In Moscow, they are strong and are convinced that their black banners will soon be the flags of freedom and true human expression.

The next section, “The Red Truth,” shows the Bolsheviks, ruling the roost since October 1918, but who represent only a tiny minority of people and whose grip on power is extremely shaky. Some parts of the trail from the robbery led deeper into revolutionary intrigues, and Fandorin is thoroughly caught in the cross-currents of armed factions, competing secret police forces, and general chaos. Virtually all of this section, however, is told from the perspective of Alexei Romanov (probably no relation), formerly a counterintelligence officer in the Imperial Army, now a fast-rising star in the Red intelligence apparatus. Probably. Two things stand in the way. First, the high mortality rate among anyone taking a leading part in the political struggles of revolutionary Russia. Second, he might just be playing his own game among the Reds and go over to another faction — probably the Whites — at an opportune moment. This section gives a sense of the back and forth among the groups competing for power, how something close to chance pitted former comrades against each other, and how intra-faction conflict could be as deadly as that between groups. Everything is up in the air, and nobody knows anything for sure.

“The Green Truth” begins with an artist, Mona, who is also looking to escape Russia via the southern routes. She gets into a tight spot on a river raft, but is saved by Fandorin, who is in disguise as a wandering monk. Where are they headed?

In the ‘twilight zone’ between the Reds and the Whites, dozens of steppe republics had sprung up, each with it’s own ‘bat’ko’: The ‘Chyhyryn Commune’ of Bat’ko Kotsura, the ‘Holodnoyarsk Council’ of Bat’ko Chuchupak, the ‘New Camp’ of Bat’ko Bozhko, the ‘Knightly Cossack Host’ of Bat’ko Angel and a certain ‘Green School Directorate’, but the ‘bat’ko’ most talked about had been the Gulyaypolye ataman Makhno.

The Green areas were various peasant-dominated communes that disdained Moscow and Petersburg, and that harkened back to Cossack ideas of freedom. Partly anarchic, partly locally authoritarian, these were a hodge-podge of small and uncertain polities across central Russia’s richest agricultural lands. Along the river, though, Mona and Fandorin acquire two other travelers, and the war begins to take an interest in them as well. The intrigues of the first two sections begin to show themselves even in the remote areas where the Green peasant groupings are trying to keep the world at a distance.

More scrapes follow, and they land among the remnants of the Imperial Army in and around Kharkov, now Kharkiv, Ukraine. The Whites are pressing the Reds, hoping for a breakthrough that will provide an open road to Moscow. Their flanks, though, are open to disruption by Green and Black forces. They also appear to have spies in their midst, as Bolshevik operations are striking at the Whites’ resources and at some of their senior commanders. Akunin tells a significant part of this section from Alexei’s point of view as well. Is he a Red pretending to be a White, or is he truly a Bolshevik? What about his closest comrades in both organizations? Are some of the Whites really Red, and might some of the Reds be feeding information back to the Whites? If the Cheka is a deadly rival to military intelligence, isn’t that as bad as being White? Fandorin would like to proceed to Sebastopol and out of Russia entirely, but personal entanglements and his commitment to investigations keep pulling him back in to the morass.

One of the joys of this novel is that despite the subject matter and the questions addresses, it remains light and fast throughout. Fandorin is funny, and Akunin has not forgotten the pulpy origins of the detective story. He honors them with feats of deduction and derring-do, with characters who reveal unexpected abilities, and sudden romances. It all feels of a piece, though, and the improbabilities charmed me rather than kicking me out of the story. Not Saying Goodbye is a classic Fandorin adventure on a par with The State Counsellor or The Coronation.

In fact, about the only thing I did not like about Not Saying Goodbye was the final ending, after the four sections showing paths that Russia might take. (Spoilers, obviously.) Arthur Conan Doyle famously got tired of Sherlock Holmes and sent him to his presumed death, hurtling over the edge of the Reichenbach Falls, a drop of some 250 meters. Just as famously, the public outcry caused him to bring Sherlock back for more adventures. I don’t know if Akunin grew tired of Fandorin, or if this denouement was planned from the beginning. Akunin decided early on that each Fandorin book would address a different subgenre of detective story, and that the stories would advance through history and the character’s lifetime. On the one hand, Bakunin nearly killed Fandorin at the end of The Black City. I don’t know enough to say whether this apparent death and return for another adventure were the result of public devotion to Fandorin, or if Akunin was echoing Doyle’s actions as yet another commentary on the detective genre. I do think that Fandorin deserved a happy ending, and not what Akunin did to him.

I began reading the Fandorin stories when my oldest child was barely a toddler, and have now finished them when he is in his first year as a university student. Fandorin has been a fictional companion for quite a stretch of my life. I have enjoyed his adventures, his verbal tics, and the things that a long-time reader knows and his adversaries do not: how he never loses at games of chance, that when he loses his stammer things are about to get very serious. I have enjoyed Akunin’s takes on different styles of stories, and getting to see Imperial Russia from a different, often funny, perspective. I wish that Akunin had given him the chance to sail off into the sunset or, possibly, toward the rising sun of Masa’s homeland.

+++

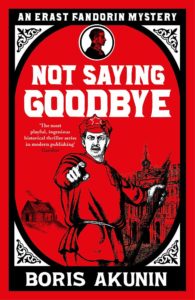

Not Saying Goodbye is the thirteenth and last book in the Fandorin series, at least as it is published in English. It is probably the worst possible place to begin reading the series. I think that in the first book, The Winter Queen, Akunin was still finding his feet, and recommend beginning with the second, Leviathan, or the third, The Turkish Gambit.

2 comments

1 ping

I am now girding my loins for this novel, tho I’m very, very far behind in my Akunin/Fandorin reading.

Author

I waited a long time because I knew it was the last one. Mostly, I thought it was more fun than its immediate predecessors. Fandorin is b-back! That is one.

I’m also led to understand that some of the characters in this book appear in other B. Akunin stories. If I read the Wikipedia entries correctly, there’s one Russian volume that has been translated into two books in German but not into English at all. Then there’s Planet of Water. All I have to do to read that is learn Russian.

Still love the series as a whole.

[…] in 2023 I said good-bye to Erast Fandorin, at least for the first read-through. I’ve been reading this series about […]