Time for some short takes to clear the desk for the coming year.

Primeval and Other Times by Olga Tokarczuk. Nobel winner Tokarczuk uses very short chapters, each titled “The Time of …”, to depict life in an archetpyal Polish village from just before the outbreak of the First World War through the last years of the communist period. While the details are specifically Polish, the name makes clear that the village is meant to stand in for universal social and human experiences. Tokarczuk ventures a bit into the mythopoeic, turning a beggar girl from one of the first chapters into Cornspike, something of an earth mother of the nearby forest, a counterpoint to the respectable women of the village, someone who couples with a ghost and gives birth to a daughter with unusual powers. Tokarczuk also gives chapters to the icon of the Virgin in a nearby town, the soul of a drowned man, an “instructive game for one player,” a network of mushrooms extending through the whole environment, an orchard, and, once, God. She concentrates on three generations of one family, and their closest village acquaintances. The book is short, the people are mostly interesting, and the incidents are convincingly arranged. I think that Tokarczuk danced right up to the mythical, and then skittered away without following through; I don’t know if she was afraid of writing an out-and-out fantastical book, or if she thought hints were sufficient for her purposes. As it was, Primeval and Other Times felt more like a promise unkept.

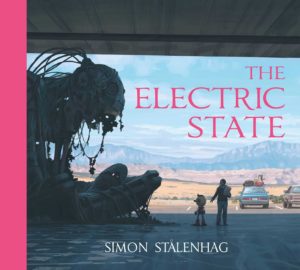

The Electric State by Simon Stålenhag. The art in this large and gorgeous book plonks the remains of gigantic, half-destroyed battle robots into a nearly deserted landscape of an alternative 1990s California. Some of the robots have friendly amusement-park faces to add glee to the menace. Meanwhile, vast mushroom-shaped installations lurk in the background, emanating a red glow from layers of fortress windows and tethered to the landscape by vast numbers of tentacle-like cables. Few people remain to be seen, and most of those few hide permanently behind their VR helmets. Clearly something terrible, and yet terribly beautiful, has happened. The Electric State is Stålenhag’s third book, following Tales from the Loop and Things from the Flood. The other two similarly juxtaposed science fictional objects with mundane settings; they were set in his native Sweden, while The Electric State moves to America. The story itself doesn’t make a whole lot of sense (though its ambiguous ending is the best part about it). Doesn’t matter. The paintings capture a whole gorgeous menacing mood and are better prompts to the imagination than companions to a text.

Humankind: A Hopeful History by Rutger Bregman. Humankind considers what Bregman says is the radical notion that most people are good, most of the time. Bregman argues against some of the most famous artworks and social experiments that have depicted humans as eager to be horrible to one another. He found a real-life Lord of the Flies situation, in which Tongan schoolboys were stranded on an island for more than a year. After their rescue, they were in good health, and the preferred solution when conflicts arose was to separate the boys until they settled down. The Stanford Prison Experiment was not only flagrantly unethical, but it was stage-managed behind the scenes to increase conflict and bad behavior. Most people resisted giving simulated shocks in the Milgram psychological experiment. The expected breakdown of civil order during strategic bombing in World War II never happened, regardless of who was doing the bombing. Bregman touches lightly on evolutionary reasons that friendliness might have given homo sapiens a leg up on neantherthalensis and other species co-existent in pre-history. He talks about the long career of the idea that civilization is just a thin veneer, and that strong rulers are needed to rein in brutish humans. He thinks it’s an idea whose time has gone, and he marshals considerable evidence for why. Humankind is enlightening and hopeful, though it’s maybe a little short on the staying power of racism and, particularly, sexism. I found it well worth the time to read, and a well-argued counterpoint to gloom and doom.