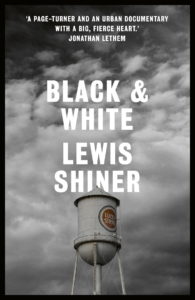

I went and checked, and Lewis Shiner never did reconcile with his father. Terrible fathers feature so prominently in several of his novels — Glimpses (1993), Outside the Gates of Eden (2019) and Black & White (2008); maybe also the other three that I’ve read, but it’s been so long that I do not remember for sure — that it was impossible for me not to think that there was a real-life model behind them. In Glimpses the protagonist’s father is dead from the start of the book, so no reconciliation is possible. In Eden the break between Cole and his father is also irretrievable, but the novel offers positive alternatives, particularly in the Montoya family, and it follows its characters long enough that some of them become parents themselves, trying to do better.

Black & White changes the dynamic a bit: The father wants desperately to reconcile with his son Michael, or at least to explain, but cannot bring himself to say so directly. He is dying of cancer but insists on moving from Dallas, where the family had moved when Michael was an infant, to Durham, North Carolina for his final days. Robert, the father, and Ruth, the mother, met there, though they grew up in different parts of the state. Robert was from Asheville, where his parents had worked as servants on the Biltmore estate; Ruth was from rural Johnston County, where her father was a farmer and a local bigwig. They married in 1962, and Robert started a career in construction, working as an engineer for a company that was key to building the Interstate through Durham, before the three of them suddenly moved to Texas and cut off all contact with Ruth’s family. Michael thinks that his father is trying to say something by going back to Durham to die, something that will explain the cold home he grew up in, something that will fill in the blank pages where most people have a book of family history. Black & White is the story of what he finds out.

Intertwined with the personal story of Black & White are stories of power and race, and economic change, in the American South. Durham had been an agricultural center, and then a hub for collecting tobacco and manufacturing products from it, mostly cigarettes. By the early 1960s, though, the mills and the headquarters of the tobacco companies had all left, and the city’s economic lifeblood had nearly all drained away. North Carolina’s research triangle, which drives Durham’s economy today, was still sketches on a civic booster’s whiteboard. To make that happen, roads — Interstates — connecting the cities of the triangle had to be built, and those roads had to go somewhere. And where it went was right through the thriving Black business district of Durham, called Hayti (pronounced “Hay-tie”). Robert’s company was the one that tore down most of Hayti. As Ruth says when the time comes for her to finally tell her story:

Now Robert was the reluctant hand of that [destruction]. She knew it didn’t sit well on him, and she wished she could ease his mind. It wasn’t like there was another way for this to turn out. Durham needed the highway so people could get to the new business park. The city would die without it. The highway was going to displace somebody, anywhere you put it. It only made sense that it was the poor people that had to move. It would cost a hundred times more to buy up rich people’s houses.

They told Robert a new, better Hayti would rise from the ruins, and he wanted to believe it. Ruth let him, and never said a word about her father’s prophecy. Between the word of Mitch Antree [head of Robert’s company and devotee of Hayti] and the word of Wilmer Bynum [Ruth’s white supremacist father], she knew which would prevail. (pp. 288–89)

Black & White begins and ends in 2004, but goes back to the 1960s in two long sections that tell the stories of Robert and Ruth. Michael learns much about both of his parents, including many things that neither ever told the other. It is a rich and satisfying novel, one that explains people without excusing them, that shows the contradictions that people live with, and how people facing similar constraints and opportunities make different choices. Even within Durham’s Black community, for example, there were different views about Hayti, different responses to its destruction. Shiner captures both eras, bringing life and complexity to pictures that are often seen in black and white.

(Spoilers follow about what Michael learned.)

Michael leaves the vigil at his father’s bedside to try to discover why Robert chose to return to Durham. His parents had never talked about their past, just one of the many silences that made his childhood so different from other people’s. He has a very few names for his father’s story, all related to the company that his father worked for at the time. On his mother’s side, he knows his grandfather’s name and has a rough idea where the family farm is. On a visit to the farm, he finds people in the county wary of Wilmer Bynum’s name even two years after his death. Michael finds the current owner of the farm, a cousin, more than wary. During a brief visit to the big house, which the cousin keeps tidy even as he lives in much smaller quarters on the grounds, he makes one of his first discoveries: his mother had had three sisters, not the two he had previously been aware of.

In Durham, Michael starts out with the name of the company his father worked for and branches out from there. The founder is deceased, as is one of the men Robert had mentioned as his right and left hands during the work in Durham. Tommy Coleman, though, is still alive. On the telephone Michael addresses him as “Mr Coleman” and adds in the polite “sir” that Southerners often use when addressing older men, but also that no white man would have done for a Black man back when Robert and Tommy Coleman were working together. He, too, is wary.

“What is it you want to talk about?” [said Coleman].

“About my father. Maybe you were working with him when I was born. I would like to know about that.”

“I don’t really know anything. I just worked for him, that’s all.”

“Mr. Coleman, what is it you’re so afraid of?”

After a long half minute, Michael said, “Mr. Coleman? Are you still there?”

“Yeah, I’m here.” Michael heard the surrender in his voice. “There’s no getting away from it, is there?” (p. 21)

What there’s no getting away from is that late one night the owner of the construction company called Coleman and his uncle Leon to bury a body in part of an overpass they were working on. Bury it by pouring concrete over it at some time after two in the morning. The owner drove the cement mixer, and Coleman saw Michael’s father in the passenger seat. The body was Barrett Howard, a local Black activist who was leading resistance to the destruction of Hayti and otherwise making life uncomfortable for the local white power structure. Soon after, rumors emerged that Howard had taken all of the money from his fundraising and run off to Mexico. The highway got built, Hayti never got rebuilt, and Robert took Ruth and Michael off to Texas for a new life.

Michael thinks that his father may have been the murderer, and that is one of two reasons he confronts his father in the hospital. The other is that he discovers his father was much closer to Hayti than he had ever thought. Not only did he spend most of his free time there, he had a long-standing affair with a woman who lived there. Shiner puts the revelation in the hands of Mrs. Camilla Prentiss, an older Black woman, someone Michael finds through an oral history transcript and then goes to visit.

“That woman had so many contradictions it was impossible to know what to think,” [said Mrs. Prentiss.] “She was what they used to call a high yellow gal, skin light enough that she could have passed if she wanted to. Long wavy black hair. Looked like one of those Italian actresses, Sophia Lollapalooza or whatever. Some said she had a double life, that she was passing in her day job. … Here she is going around with Barrett Howard, who was black as the ace of spades and shouting from the housetops about black power, and the self-same time she’s messing around with a white man.”

Michael had brought the printout of the [company founder’s] obituary. “Is this the white man she was messing with?”

“No. I might have seen this man around at one time or another. She did have some wild parties there. But that’s not the white man that was more or less living there with her.”

“Can you describe him?”

“I don’t have to describe him. Go look in the mirror, you’ll see him.” (p. 76)

Armed with that information, Michael demands that his father tell him the truth. The next 125 pages of Black & White give readers Robert’s story in full, revealing a man very different from the cold and distant father he had grown up with, a man who loved to dance, a man who wanted to make his mark in the world, a man who struggled with how the view of race relations that he had grown up with conflicted with the evidence of his eyes and ears. Shiner gives a sense of the momentous changes of the mid-1960s, how the people caught in them reacted in their various ways, worked to see the world anew or worked to keep those changes from happening. I was struck by how the Black people on the construction team talked with the other Black people whose businesses they were knocking down. The racial conflict was also, in this aspect, a generational conflict.

Delving into Barrett Howard’s death shows Michael that the conflicts from the 1960s are far from over. As he discovers more than the police investigators (much to their annoyance), signs point away from his father and towards Ruth’s family. Her father was a political player, and in 1950s and 1960s North Carolina that meant that he was a violent upholder of white supremacy. The organization that Shiner describes in Black & White, the Night Riders of the Confederacy, continues to be active into the novel’s present, though it is careful to claim it ceased its violent activities long ago. Ruth’s father headed the NRC, even as was rumored to have fathered several children with Black women in the area. Howard was a natural target for them. News of this connection forces Ruth to tell her story, and it is both a horror and a tragedy, an example of love and trauma, and the lengths to which someone will go to protect their view of themselves and their sense of what their station in life should be.

If there’s one thing Black & White does best of all it’s capture the inevitable entanglements in a society where one part is exerting all of its might to keep it separate from, and on top of, another part. There is no ultimate reckoning because many things can never be made right, and all of the people will continue to be there side by side. Michael chooses a side, chooses to try to settle in Durham, even knowing that the events at the end of the book will leave him in danger in North Carolina. It’s not a simple black and white binary, but then nothing ever has been.