The receipt tucked away in the pages of this collection tells me that I bought it in early 1997, in Washington, DC. At that time, I would only have read Heaney’s Nobel lecture. His Beowulf, the first poetic work of his that I read, was still two years from publication. There’s another receipt in the book, for a handlebar bike bag. That would have been part of my preparation for a two-week bicycle tour in northern Poland that I took in the summer of that year. Poland loomed large in Heaney’s intellectual landscape, thanks mainly to a friendship forged in California with Czeslaw Milosz. In 1995, he had published a version of the Laments of Polish Renaissance poet Jan Kochanowski, co-translated with Stanislaw Baranczak. In those days I could read almost enough of the Polish to measure it against the rendering in English.

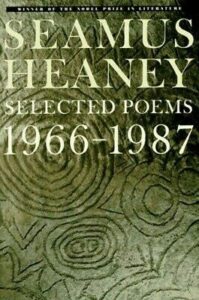

The bicycle bag went with me to Poland (I may have it still), but the Heaney collection did not. In fact, I did not crack it much at all until this year, when I had already read nearly all of the volumes that this selection draws from. The Selected Poems covers exactly the seven major collections that I have written about for Frumious, with two additions. As an introduction to Heaney’s poetry and an overview of the first half of his career, the Selected Poems is a good book. He draws more heavily on the collections that were more recent when this volume was published: there are seven poems each from Death of a Naturalist and Door into the Dark, with more than twice as many from The Haw Lantern and more than three times as many from Station Island, including the 20-page title poem. Looking through the table of contents and comparing it to my notes on the various collections, I did not see anything that Heaney omitted that I sorely missed.

The two exceptions are Stations a twenty-four page collection of prose poems that Heaney published in 1975, and Sweeney Astray, his crack at the medieval Irish work Buile Shuibhne, which he published in 1985. Stations was a formal experiment, the sort of thing poets do to stretch themselves and stretch their art, to see if there might not be more ways of doing the things they want to do than they had been previously accustomed to. Of the seven that Heaney selected for this volume, I most liked “Cloistered,” which draws a line between schooling and monasticism, playing on the many ways that people may be set aside from the world. “Trial Run” and “Visitant” catch ambiguities of Ulster’s situation in the world of the 1940s and 1950s. It was interesting to see Heaney try out this form, but on the whole I am glad that he did not pursue it.

The five bits from Sweeney Astray come from a different era entirely, and sing in a different register. He captures the madness and the sadness of the king transformed and cursed to wander until the prophecy of his death is fulfilled. Along the way, though, he also captures bright joy at the simple being of trees (in “Sweeney Praises the Trees”) or birds (in “Sweeney Astray”) that is less complicated than one of Heaney’s own poems, but just as beautiful.

I’ve preferred the luxury of reading Heaney’s full collections, but it’s nice to have this selection, and for someone who wanted to dip into his poetry without diving in completely, this is a good place to start.