Hrm, well, if I’d known this was essentially a memoir by a woman in her 40s, I would have probably skipped it (as I do for memoirs by men in their 30s, and for roughly the same reasons.) I feel that the 40s are a bad age for a woman to try to do a retrospective on her life, and I think it has a lot to do with how Western thought has taught us that this is an age where we’ve achieved enough wisdom to look back on our lives and even-handedly consider them. Because, too, memoirs at this age seem to be a complacent “this is how I’ve achieved happiness” how-to, and then half the time reading them, I’m cringing because the author clearly has a lot of sublimated misery that another decade will absolutely help her figure out. Weirdly, memoirs by younger women don’t have this problem, probably because they’re not expected to have all the answers yet and are usually focused on single events or topics instead of being a whole life retrospective.

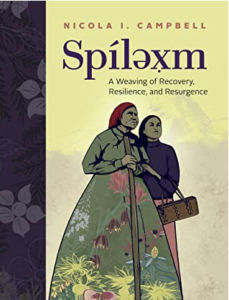

I actually didn’t realize this was a memoir at all when I started it: I thought it was the transcription of an oral history, or a collection — a weaving, as in the title — of the stories of a people, perhaps a family. And in large part, it is, or at least that’s where it begins, with letters written from Nicola I Campbell’s mom from when the author was a baby. Ms Campbell’s poetry is interspersed with short personal essays that detail her childhood and troubled adolescence, and how she assimilated her people’s culture and pain as she grew, eventually focusing on personal growth and then the upholding of her people’s ways and memories. Worthy aims certainly, and there are a lot of ways in which that last is manifested throughout this book. The use of Indigenous language and the frank discussions of the intergenerational trauma that continues to impact her and her people make for compelling reading. The poetry, too, isn’t bad.

I actually didn’t realize this was a memoir at all when I started it: I thought it was the transcription of an oral history, or a collection — a weaving, as in the title — of the stories of a people, perhaps a family. And in large part, it is, or at least that’s where it begins, with letters written from Nicola I Campbell’s mom from when the author was a baby. Ms Campbell’s poetry is interspersed with short personal essays that detail her childhood and troubled adolescence, and how she assimilated her people’s culture and pain as she grew, eventually focusing on personal growth and then the upholding of her people’s ways and memories. Worthy aims certainly, and there are a lot of ways in which that last is manifested throughout this book. The use of Indigenous language and the frank discussions of the intergenerational trauma that continues to impact her and her people make for compelling reading. The poetry, too, isn’t bad.

And yet, and yet. While I appreciated the glossary at the end, I wish there’d been a pronunciation guide as well, so that my brain could spend more time on the prose and ideas rather than mulling over whether I was pronouncing the words properly in my head. Never mind not knowing what half of them meant in the moment: I could gather enough from context but kept snagging on how to correlate spelling with sound, with failure resulting in a sort of white noise effect in my head — very distracting when trying to read. There’s also a weird, crescendoing emphasis on exercise, such that when she finally mentioned she does Crossfit, my eyes rolled so far back in my head, I nearly gave myself a concussion. Contrast this with my impatience with her younger self’s waffling about canoeing in earlier chapters. As someone whose adult-onset asthma has sharply curtailed the amount of exercise I can get these past few years, I found the “just do it” chirpiness of the newly converted incredibly grating. If only, madam, if only.

But the greatest flaw of this book is the lack of thematic structure, with themes repeated in ways that feel less intentional than sloppy. While I was grateful for the insight into the lives and culture of the Indigenous people of present-day British Columbia, as well as for the throughline of the prose narrative following the author’s own life, I wished there had been greater rigor in addressing, particularly, controversies and personal tragedies. Euphemisms do a lot more work in this collection than is warranted. If you’ll allow me to make one here myself: while I get that weavings are supposed to allow for a blend of color and material, the best ones depict clear pattern and form, displaying the weaver’s mastery of the art. A weaving that’s just a muddied jumble is still a weaving, sure, but it’s merely functional, not the kind of art you’d expect in a book that presents itself this ambitiously.

Perhaps I am being too hard on this memoir. While the first three-quarters are pretty good, the last quarter just gets weirdly repetitive and anxiously self-indulgent, as if the author knows this isn’t a good way to end this book but doesn’t know how to make it better (hence the blathering about exercise and the story about biking that even I, as an avid bicyclist, thought hella weird in the context of the rest of the volume.) I did appreciate her support of LGBTQ+ rights, tho thought her injunction to love and forgive ourselves, while coming from a good place, felt like a facile attempt to cap the story instead of engaging properly with concrete ways to change the system that scarred her and her people so indelibly to begin with. Healing is good and necessary, but so is action and prevention, and just shrugging off the racism of white people isn’t enough. Education, at least, is a good start, and as an accessible enough guide to the author’s Indigenous culture, this is fine. I just feel that it had the potential to be so much more.

Spílexm: A Weaving Of Recovery, Resilience, And Resurgence by Nicola I. Campbell was published September 28 2021 by Highwater Press and is available from all good booksellers, including