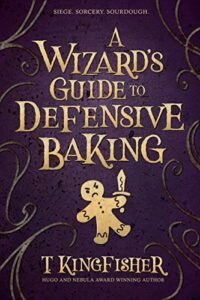

“There was a dead girl in my aunt’s bakery.” There’s the first problem right away. Worst of all for the dead girl, of course, but a horrifying start to the day for Mona, the fourteen-year-old first-person narrator of A Wizard’s Guide to Defensive Baking. Then things get worse.

Not right away, of course; Mona partly distracts herself from the horror of the body in the kitchen (“the red stuff oozing out from under her head definitely wasn’t raspberry filling”) by thinking of worse things that have been in the kitchen, like a zombie frog that had crawled in from the canals.

Poor thing had been downstream of the cathedral, and sometimes they dump the holy water a little recklessly, and you get a plague of undead frogs and newts and whatnot. (The crawfish are the worst. You can get the frogs with a broom, but you have to call a priest in for a zombie crawfish.) (Ch. 1)

Like a sensible young teen, Mona knows when she’s out of her depth. She decides to wake her Aunt Tabitha. “Not that Aunt Tabitha had bodies in her bakery on a regular basis, but she’s one of those competent people who always know what to do. If a herd of ravenous centaurs descended on the city and went galloping through the streets, devouring small children and cats, Aunt Tabitha would calmly go about setting up barricades and manning crossbows as if she did it twice a week.” (Ch. 1) It will turn out that Mona is one of those people too, though she does not know it at the outset. She discovers how much she can do by seeing what needs to be done and setting to it, even when the adults around her are scared or unable.

The setting is a standard fantasy city — one of many in the lands, ruled by a Duchess, defined by a river and numerous canals, tolerant of magic users — because Kingfisher (a pen name of Ursula Vernon) is far more interested in exploring the nuances of people than the details of places. What happens when, say, a murder victim turns up in their bakery? Or indeed in the local bakery where they get their favorites? Though of course Mona and her aunt don’t say “murder” at first because even though two constables had come out and one had gone to fetch the coroner, they were still a respectable bakery.

I repeated over and over again that everything was fine, somebody’d just broken into the kitchen and the police were looking at it, but nothing seemed to have been stolen, and we hoped to be open for business later today.

“Nobody’s safe anymore,” said old Miss McGrammar (one lemon scone, no icing) with a sniff. She rapped her cane against the counter for emphasis. “Imagine, someone breaking into a bakery! We’ll all be murdered in our beds soon and no mistake!”

“Some of us sooner than others,” muttered Master Elwidge, the carpenter (two cinnamon rolls, one loaf of cheese bread) winking at me.

“Hmmph!” Miss McGrammar shook her cane at him. “You can laugh! Little Sidney, the boy of Mrs. Weatherfort who does the washing, he went missing just last week, and have they seen hide nor hair of him since?”

“No?” I ventured.

“They have not!” She smacked her cane down like a judge’s gavel.

“Probably ran away to sea,” offered Brutus the chandler (one of whatever looks good today, m’dear, and a loaf of the day-old for the pigeons if you have it).

“Even good boys will be boys,” said Brutus mildly, rubbing his forearms. He had several faded tattoos, and I suspect he was speaking from personal experience.

“Sidney Weatherfort wouldn’t run away to sea,” piped up the tiny Widow Holloway (one blackberry muffin, two ginger cookies, and thank you so much, dear Mona, you’re getting to look like your poor dear mother every day, you know…) “He was a magicker, and you know how superstitious sailors are about taking on wizard-folk. They think the winds will fail if you’re carrying wizard-folk aboard.”

“A magicker?” Elwidge looked surprised. “I didn’t know that.”

“He was a mender,” said the Widow Holloway. “Little things. He fixed my glasses for me once when the lens cracked, and I thought I’d have to send away to [another city] to have a new one ground.” She smiled at me. “Small things, though. Nothing like as good as our Mona, here.” (Ch. 2)

Kingfisher advances both character and plot with light touches in exchanges like these. Miss McGrammar is more right than the others will allow, but not in the way that she thinks. Master Elwidge has, as Mona says, just enough magic to take the knots out of wood, and will turn out to know things about disappearing at the right time. Because the girl in the bakery is not the first victim of a particular kind of murder, nor the last, and even more sinister things are afoot. The bakery scene also shows how wizards live precariously, even in a city that officially views them positively. Some like what magic can do, some don’t like any of it — Mona has overheard people say they don’t go to her bakery anymore since it became known that she can do magic — and even the well-disposed may say or think, “Well, you can never be sure…” As a result, many wizards practice quietly, maybe even invisibly to non-wizards.

Magic is also unpredictable, and mostly intuitive. As Mona describes what she did when she realized she had been kneading the sweet bun dough too long: “You don’t want to knead [sweet buns] too much, or it makes them tough. I stuck a floury hand in the dough and suggested that maybe it didn’t want to be tough. There was a sort of fizziness around my fingers and the dough went a little stickier. Dough is very amicable to persuasion if you know how to ask it right. Sometimes I forget that other people can’t do it.” (Ch. 1) Magic also responds to the emotional state of the wizard. “I … shoved [the sweet buns] into the oven with strict orders that they didn’t want to burn. They wouldn’t. Not burning is one of the few magics I’m really good at. Once, when I was having a really awful day, I did it too had, and half the bread wouldn’t bake at all.” (Ch. 1) And it takes both practice and growing up to gain control. Mona was a small child when she taught gingerbread men to dance. She no longer remembers how she did it the first time, but now it has become a signature, and the bakery nearly always has a few on hand to dance for customers or, occasionally, help push things on high shelves forward so Mona can reach them. Then there’s Bob.

Bob is my sourdough starter. He’s the first big magic I ever really did, and I didn’t know what I was doing, so I overdid it. …

When I first started working in my aunt’s bakery, I was just ten, and I was really scared that I’d screw something up. My magic tended to do weird things to recipes sometimes. So I was put in charge of tending her sourdough starter …

I don’t know if I gave it too much flour or too much water or not enough of either, but it dried up and nearly died. When I found that out, I was so scared that I stuck both hands into it (and it was pretty icky, let me tell you) and ordered it not to die. Live! I told it. C’mon don’t die on me, live! Grow! Eat! Don’t dry up!

Well, I was ten, and I was really scared, and sometimes being scared does weird things to the magic. Supercharges it, for one thing. The starter didn’t die, and it grew. A lot. It foamed out of the jar and over my hands and I started yelling for Aunt Tabitha, but by the time she got there, the starter had reached the sack of flour I’d been using to feed it and ate the whole thing. I started crying but Aunt Tabitha just put her hands on her hips and said, “It’s still alive, it’ll be fine,” and scraped it into a much bigger jar and that was the beginning of Bob. (Ch. 1)

For a short book with such a light touch, A Wizard’s Guide to Defensive Baking has a lot in it. There’s not just the main story of Mona and what happens when the authorities arrive — the constables may mean well, but the system just wants to blame someone, anyone — there’s also what happens when the dead girl’s brother turns up, too. There’s poverty and madness, power and corruption, and a threat to the city as a whole. Yet the tale is never bleak, partly because Kingfisher leavens even the most fraught moments with whimsy, but mainly because her main characters are fundamentally good people, despite their flaws. I keep coming back to it, reading small sections, savoring the brilliant moments and basking in the warmth of a well-baked tale, with just the right amount of frosting.

2 comments

1 ping

I love the concept of defensive baking.

Author

And the applications are even better!

[…] glad that it exists. Even if I can think of better books in a similar vein. T. Kingfisher’s A Wizard’s Guide to Defensive Baking and Emily Tesh’s Silver in the Wood spring to mind, though both have darker, deeper […]