Some time past the middle of the twenty-first century, Britain offers its citizens the safest, most democratic, best-adjusted society in human history.

Every person under the System is encouraged — though not compelled — to spend a certain amount of time each week voting, and is semi-randomly assigned to decision-making bodies for the duration of their session. Each body will most likely be around two hundred individuals strong, and will deal either collectively or in subcommittee jury group with anything from asylum requests or the allocation of medical resources to commercial disputes. It is the most nuanced and democratic system of direct governance ever devised, and it requires genuine participation from the polity. For the body of the state to perform its function properly, each person must make his or her own decision in the light of their personal experience and opinion without being influenced by others at the formative stage, so sessions are initially private and remain anonymous throughout. Each problem is proposed to each person in a way that is fractionally different, tailored precisely to pique their interest and understanding, their self-interest and their altruism, so that every choice is made with the greatest awareness of consequence and meaning. (p. 25)

But the workings of a utopian participatory democracy are not what Gnomon is about. They are the necessary foundation of a story — or more properly a nested set of stories — that is both wider and deeper. It begins with Inspector Mielikki Neith making a televised statement about the death of a suspect in the custody of the Witness, while people use the System to examine her microexpressions to gauge whether her pained honesty about how everyone at the Witness feels this failure is faked, and Neith herself follows the polling numbers that trail across her screen. Or maybe it begins with the death of Diana Hunter, the death that distresses Inspector Neith because of the failure it implies, though Hunter’s case will do much more than distress her as Gnomon proceeds. Or maybe it begins with Hunter being called in for interrogation. The first words that she gives to the System are the title of the first section of Gnomon, “my mind on the screen.” In fuller form:

“I can see my mind on the screen.”

Hunter’s first thought during the examination is like the barb on a fishhook, and Neith instinctively loathes it. These eight unremarkable words cause her to tighten her jaw as if expecting a blow. The phrase is, to be sure, unusually clear and strong, quite ready to be vocalised. One must assume that Hunter was deliberately recording a message, in which case: to whom? To Neith, as the investigating officer? Or to an imagined historian? Why does the tone, the clean, discursive flavour of Hunter’s mind, trouble that part of the Inspector that is devoted to a professional mistrust of appearances? (p. 10)

A gnomon is the bar sticking out from a slab that turns a flat surface into a sundial. Its intrusion changes a physical phenomenon into a source of meaning and measurement. “In geometry, a gnomon is a plane figure formed by removing a similar parallelogram from a corner of a larger parallelogram; or, more generally, a figure that, added to a given figure, makes a larger figure of the same shape.” Gnomon is filled with such irruptions, things that intrude among planes, cast shadows, and change meanings.

Diana Hunter should not have been where she was, she should not have died as she did, and she definitely should not have been able to give such a clear sentence to the Witness. She was a mid-level administrator and “then later a writer of obscurantist magical realist novels, she was apparently once celebrated, then reclusive, then forgotten.” Her most famous book was “arguably the last, titled Quaerendo Invenietis, which received only a very limited publication and became an urban legend of sorts, with the usual associated curiosities. Quaerendo contains secret truths that are downright dangerous to the mind, or an actual working spell, or the soul of an angel, or Hunter’s own, and the act of reading it in the right place at the right time will bring about the end of the world, or possibly the beginning, or will unleash ancient gods from their prison..” (p. 9) The title means “You will find by seeking.”

Seeking is exactly what Inspector Neith does, and one of the first things that she finds is the anomaly of Diana Hunter (a mythologically laden name, unless it’s simply mythological?). Neith’s reaction to Hunter’s first statement — “I can see my mind on the screen.” — tells readers much about the society in which both of them have been living.

Perhaps [the statement] is suspicious for its very competence. There’s no record of Hunter having the kind of training that would allow her to be so coherent. Her record [from the interrogation] should be a ragged but truthful account of her self: less a cut-glass cross section than a jellied scoop lifted from a bowl. It was a minimum-priority interview until Hunter died, a lot-to-no-likelihood examination based on a direct tip-off using the precise form of words given in the Security Evidence Act, and some ancillary factors to score a level of certainty just barely topping the margin of error. There are twenty or thirty such each month: full investigations carried out on the precautionary principle, no more troubling to the subjects than a visit to the dentist, and certainly resulting in no criminal cases. Statistically, those emerging from these exams are happier, more organised and more productive. It’s partly a direct consequence, the neuromedical aftercare being somewhat like a tune-up, but mostly it is a psychological blip. Everyone lives with secrets, even now — tacit self-accusations fears of weakness and inadequacy. These fortunate suspects are weighed in the balance and found worthy. The process is so universally beneficial that the Inspector has occasionally wondered if she should ask for a reading herself.

Thanks to the advanced neurological technology in Gnomon‘s setting, Neith can directly experience the memories Hunter created during her interrogation. Here are some of her thoughts before anesthesia took her, or should have taken her, into a different level of consciousness:

The machine will make any necessary adjustments for my well-being, deal with physical deformities to the brain matter, ensure there is no bleeding or swelling that might endanger me, take preventative and curative measures against sociopathy, psychosis, depression, aggressive social narcissism, sadism, masochism, low self-esteem, undiagnosed neuroatypicality, attention deficit, in other words all of the known issues of our complex biological processing, even unto the insidious and alienating cognitive dissonance and maladjustment syndrome. (You really have to watch for that one. Almost anyone can have it.)

Or you could say that in twelve hours I will have betrayed everyone I love into the hands of these my torturers, and we will all of us emerge perfected and adjusted and happy and enslaved. We will be remade in the image of a creation I once believed was the only way to avoid horror, but which by a ridiculous string of errors and confusions of the mind is now a horror in itself.

They take off the blindfold. Some of the processes require visual stimuli. I look at the room, at the screens all around me, at my self everted on them like a rat on a middle school laboratory counter. …

I think: You shall not have my mind.

It comes up on the screen, in sans serif font.

Do the interrogators have Hunter’s mind? Does Neith? And if they do or she does, will it help in figuring out why Hunter died?

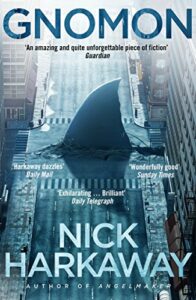

When Neith next has an opportunity to play back part of the interrogation, she does not find thoughts and memories from Diana Hunter. She finds memories of a Greek man named Constantine Kyriakos. In those memories, he is deep-sea diving and face-to-face with a great white shark, which should definitely not be in the Aegean but there it is, eyes and teeth and all, considering him closely while he tries not to act like prey. The shark has cut in perpendicular to Kriakos’ reality, casting a shadow across everything that follows for him.

In fact, each time Neith accesses part of the Hunter interrogation, she finds herself somewhere else entirely: Roman Egypt at the scene of an impossible but undeniable crime — in that way much like Diana Hunter dying during a routine session; with an elderly Ethiopian immigrant to Britain, an artist with a granddaughter who leads a remarkable software company. Each of these stories also features an irruption, a gnomon.

And that’s just the first layer.

1 pings

[…] takes the epigraph for Gnomon from The Emperor by Ryszard Kapuscinski. “When the first question was asked in a direction […]