I loved “The City Born Great,” the 2016 short story (and 2017 Hugo finalist) that was the seed of this novel. “The conceit of the story is that great human cities have a life of their own. Maybe that life awakens quickly, maybe it takes centuries or millennia, but at some point the genius loci becomes a thing in itself. Birth is never easy, not every potential new life makes it into the world, and Jemisin’s story tells the tale of New York’s attempt…”

In its short form, I found the story irresistible: “What makes this story great is the sheer exuberance with which it’s told. It’s fast, it’s furious, but it’s also tremendous fun. And sure, it’s a power fantasy, too, but if that gives readers sentences like ‘I backhand its ass with Hoboken, raining the drunk rage of ten thousand dudebros down on it like the hammer of God. Port Authority makes it honorary New York, motherfucker; you just got Jerseyed.’ then let a thousand fantasies bloom. It’s a story about life, and living, and that’s what it’s most full of: the very stuff of life.”

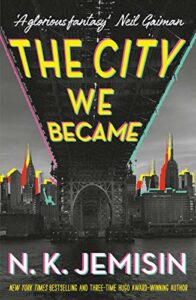

The City We Became extends and deepens “The City Born Great,” while keeping the essential story: New York wants to live, to become its most vibrant, most colorful self; something else wants to stop that from happening. A slightly revised form of the short story becomes the novel’s prologue. Instead of the battle it depicts marking the birth of the living city, it’s just the opening scene, an incomplete start, leaving the avatar of New York in unknown circumstances and its enemies still active. Each of the boroughs also has an avatar, and together they must complete the tale, though they do not know that from the start. Manny, newly arrived in the city, his past forgotten already, sharp, fast, not averse to controlled violence. Bronca, oldest of the five, daughter of the Lenape who were around when the Dutch came calling, harried administrator of an arts center. Brooklyn Thomason aka MC Free, in her younger days a rapper, now a city councilwoman, Black, formidable, and worried about her family. Padmini Prakash, Queen of Mathematics, immigrant living with her auntie, thrilled to have a chance in New York to use her abilities to their fullest, not so thrilled about all that entails. And then there’s Aislyn Houlihan, teenage daughter of an Irish cop on Staten Island, too afraid to go into the city, wanting more than anything to be left alone in the world she knows.

Each of them has an encounter with a Woman in White who seems to offer them what they want, but with a catch that will lead to the corruption of the city. Though the avatars do not initially know it, such corruption would also prevent the birth of New York as a fully living city. In his encounter, Manny has a vision of white people moving into a neighborhood in northern Manhattan, filling the parks and the buildings, with their mouths moving all the time but no words ever coming out: white people have nothing to say. He drives her off, but notices as she retreats that tubes and spores follow where she walks, all of them white, all of them attaching themselves to different parts of the city.

And that’s where I bounced out of the book the first time I tried reading it. Everything that is white is irredeemably bad. The short story had invited me in, to cheer for a protagonist who is one of New York’s most marginalized: “black, gay, homeless, teen, broke, thrown out of his churchgoing home, street artist, hustler, con man, uncertain, and scared” as I wrote in 2017. “But also confident, brilliant, unabashed, and willing. He’s terrific.” Jemisin had confidently invited all of her readers: “‘I sing the city,’ writes Jemisin to start the story. Echoing Langston Hughes, without the qualifying ‘too.’ Echoing Walt Whitman. Echoing Bradbury. Singing a new New York into the world.” With the corruption caused by all things white in The City We Became, I felt disinvited from the novel, and I was inclined to honor that disinvitation.

This struck me as different from simply portraying a non-white world. One of the things I liked best about The Mists of Avalon — and have mentioned twice here on the blog — is how it takes a story that has traditionally been very male-centric and relegates the men to the sidelines. The upending of expectations is a big part of what makes Bradley’s book so brilliant. “The City Born Great” is a non-white story, and it’s great. The City We Became makes white the marker of everything that is wrong. It’s the reversal of a trope that was present in fantasy literature for decades, and has rightly been pointed out as a serious problem and is something that reputable contemporary publishers stay away from. Jemisin has put that shoe on the other foot and gone for a book-length stroll. Which is fine, I suppose, but I didn’t see the need to come along.

Why did I pick up The City Born Great again? A couple of friends had said that they liked the book, but mainly it was the Hugo nomination that got me to continue. I’m voting this year; had I given the book a fair shake, and where would I place it in my ranking? I’m mostly glad that I did.

I would have missed Padmini Prakash if I hadn’t read the rest, and she’s a terrific character. As something of an immigrant myself, I liked seeing her determination and aspirations as crucial to the essence of New York, along with occasional exasperation at the cluelessness and alienness of her host country. She gets the job done. The action of the book is great fun, and it is full of terrific moments, often from minor characters. For example, after defeating an interdimensional menace that has arrived in a wading pool in Queens, four of the avatars (all save Aislyn) are boggled at the notion of themselves as embodiments of parts of the city. Pradmini’s neighbor Mrs. Yu, owner of the pool in question and grandmother of the boys nearly swallowed by its sudden interdimensionality, is nonplussed. “[Mrs. Yu] examines them all again, then presses her lips together in annoyance. ‘In China, many cities have gods of the walls. Fortune aids them. Relax.'” The moment of cross-cultural understanding continues:

“Okay, what the fuck,” Brooklyn says.

“Yes, exactly,” says [Padmini’s auntie] Aishwarya. Padmini frowns at her. “There are many in my country who believe that, too. Lots of stories. Lots of gods, lots of avatars—probably hundreds. Some are patrons of cities; you could call them city gods. It’s wild to think you’re one.” She glares at Padmini, whose expression takes on a sort of aggrieved blankness. An old habit of tactful silence, Manny guesses. “But if you are, then you are.”

“Yes,” Mrs. Yu opens the door more. Behind her, on one of the apartment’s couches, her younger grandson is asleep. His brother sits nearby reading a school text book as if they did not just fight for their lives that afternoon. “Real gods aren’t what most of you Christians think of as gods. Gods are people. Sometimes dead people, sometimes still alive. Sometimes never lived.” She shrugs. “They do jobs—bring fortune, look after people, make sure the world works as it should. They fall in love. Have babies. Fight. Die.” She shrugs. “It’s duty. It’s normal. Get over it.”

And there’s really not much they can say to this.

Brooklyn’s expression softens. “Sorry, ma’am. We’ve been here for a while. We should get out of your hair, shouldn’t we?”

“You saved my grandsons’ lives. But yes.” (p. 188)

Or when Bronca’s friend from Jersey City explains New York to the oldest New Yorker in the bunch:

“Kiss my ass.” Bronca says it to the dark. She’s sulking and she knows it and she wallows in it. “I hate this city.”

Veneza laughs. “Yeah, well, you New Yorkers—everybody except the new ones—always say that. It’s dirty and there’s too many cars and nothing’s maintained the way it should be and it’s too hot in the summer and too cold in the winter and it stinks like unwashed ass most of the time. But ever notice how none of you ever fucking leave? Yeah, now and then somebody’s elderly mom gets sick down in New Mexico or something and you go live with her, or you have kids and you want them to have a real yard so you bump off to Buffalo. But most of you just stay here, hating this city, hating everything, and taking it out on everybody.”

“Your cheering-up technique needs work.”

Veneza chuckles. “But then you meet somebody fine at the neighborhood block party, or you go out for Vietnamese pierofies or some other bizarre shit that you can’t get anywhere but in this dumb-ass city or you go see an off-off-off-Broadway fringe festival play nobody else has seen, or you have a random encounter on the subway that becomes something so special and beautiful that you’ll tell your grandkids about it someday. And then you love it again. It glows off of you. Like a damn aura.” (p. 295)

Passages like that invite everyone in to believe in the greatness of New York. And then the character who betrays the others turns out to be the white girl because that wasn’t the glaringly obvious narrative choice, was it.

Anyway, I also tried not to look too hard at certain parts of the set-up. Hong Kong’s avatar shows up later in the book and apparently has a quite senior status among the incarnated cities, never mind that Hong Kong was still a small fishing and salt-gleaning settlement under the British flag for less than a quarter century when New York passed a million in population in the 1870s. There’s some handwaving about how Something is slowing the emergence of living cities in the New World, but honestly, it doesn’t hold up very well. In the immediate aftermath of World War Two, for example, New York had taken over from Paris as the capital of the art world, it was displacing London as the global capital of finance, it was a major manufacturing center unscathed by the war, it was the first major home of broadcast television, it was central to recorded and broadcast music, it was home to the tallest building in the world, the list just goes on and on. If it did not incarnate then when it may well have been the greatest city in the world, why more or less in the present? Because Jemisin wants to tell a rollicking contemporary story, which is reason enough for the book, just don’t push on the justification too hard.

There’s a lot to like in The City We Became, but it isn’t the book I wanted to love after “The City Born Great.”

1 ping

[…] even Luther Vandross. The other novels on this year’s ballot are doing recognizable things: Jemisin’s book is Lovecraftian horror against superheroes who personify cities; Kowal’s is a combination of […]