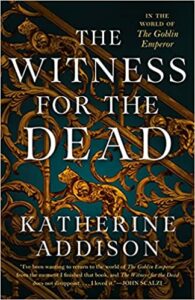

I wrote in 2015, “One last thing that I liked about The Goblin Emperor is that it didn’t end with an obvious sequel on its way. There are many stories that Addison could set in this world, and they would be a pleasure to read…” The Witness for the Dead is one of those stories, and it is indeed a great pleasure to read.

Thara Celehar is a Witness for the Dead, a cleric of Ulis with the unusual ability to contact people newly dead and return with limited information from the remains of the person’s consciousness. Usually, it’s something immediately pertaining to the person’s death, but it can be other strongly held beliefs. Celehar appeared briefly but decisively in The Goblin Emperor, using his ability to reveal crucial information about the airship explosion that set the previous book into motion. That gave him connections at the very highest level, but it also made him inconvenient to a number of powerful factions. As a result, The Witness for the Dead finds him in the large provincial city of Amalo, not quite in exile but out of the way.

Celehar prefers that situation, to be honest. He’s a member of the clergy with a true vocation and a stubborn streak of honesty that the powerful and the ambitious occasionally find inconvenient. He believes in the usefulness of his role as a Witness, someone able to bring compassion and relief to the dead, and truth to their survivors. Truth, though, is not always a relief. About a third of the way through the book, he receives a petitioner from a wealthy family who asks him to Witness for the recently departed patriarch. There are competing wills, and the uncertainty is threatening the family’s ongoing business. Not to mention that dissent strong enough to cause someone to bring forth a forged will is a sign of deeper divisions within the family. Will Celehar be able to discern the patriarch’s desired heir? What will happen to the family in either event?

That sequence illustrates one of the great virtues of The Witness for the Dead: it is not a changing-the-world fantasy novel. The world that Addison has built exists apart from Celehar, and will continue ticking along with or without him. Addison has the courage to believe that a story can be important without reconfiguring the world where it takes place, and she has the skill as an author to carry readers along on that belief.

About midway through the book, Celehar’s presence in Amalo has become awkward for its ruling prince, and he asks the witness to take care of a problem in the mining settlement of Tanvero, about two days’ journey from the city. Celehar is a cleric, and a direct appointment of the Archprelate in the capital as well, so the prince cannot command him to depart, but Celehar is wise enough to accede to the request. It also involves his calling, for Tanvero’s problem is a ghoul, one of the dead who has risen to feast on the flesh of other corpses and will eventually turn to attack the living. They can be quieted by a Witness for the Dead who can determine their name and send them back to rest. While in Tanvero, Celehar comes to know the local historian who was exiled decades ago from the imperial capital and chosen to stay in a remote settlement. The historian, in turn, asks Celehar a favor: deliver a letter to a young person back in Amalo to whom he claims a connection.

With these side stories within side stories, Addison affirms the value of all of the people in her invented world. They do not have to be emperors to be worth writing, and reading, about. Stakes in stories are not just about shaping the structure of the world where the story is set; they are about things that matter to the characters who populate it. An exile’s yearning to make a certain connection. A family’s division over inheritance. Someone’s shame at having a Witness reveal secrets. The lengths to which someone else will go to protect secrets. One person’s welding of ambition and suspicion, another’s insouciance amid different suspicions, a third’s compassion among horror.

The main story of The Witness for the Dead concerns a body that washes up on a shore of Amalo’s river one autumn morning. Who is she? How did she die? Celehar can reach enough of her fading consciousness to see her death, but nothing more. From there, his Witnessing comes to resemble detective work. She was murdered, but who did it, and why? His supernatural abilities are of no use with the living, but his long years of listening to people, listening fully and reflectively, allow him to discern a great deal even when they have little to say.

During the course of Celehar’s time in Tanvero, Addison offers some commentary that is both timeless and very timely. Celehar knows that ghouls are very real; he has quieted at least half a dozen. Yet there are a large number of people in and around Tanvero, an area particularly prone to ghouls rising from graves that are insufficiently tended, who deny their existence. “‘You would think that people would know better,’ said Tana.” (p. 103) Celehar agrees, but understands how the deniers came to that belief. The founder of their religious denomination came from the far south, where ghouls are not known, and he wrote at a time and place where the priests of Ulis had been especially corrupt. From there, it was a short jump to denigrating priests as a whole and insisting that things such as ghouls were superstitions to prop up the wealth and power of the clergy. When those people moved north to Tanvero and surroundings, they kept their beliefs in the face of direct evidence to the contrary. Even when those beliefs cost some of them their lives.

“But how can they think ghouls don’t exist?” she said, almost plaintively.

“I can’t explain belief,” I said. “I can’t explain why anyone listened to [the founder], except that they, too, were angry at their priests. And once you decide your priests are parasites and their teachings are worthless … the [followers] are proud of not believing in anything they haven’t seen for themselves.” (p. 212)

Celehar’s compassion for everyone, with the possible exception of himself, is another of the book’s great virtues. He can see why people do what they do, which helps him both as a member of the clergy and, in a different register, as a detective. Over the course of The Witness for the Dead, he finds many truths, bringing readers along for stories that are important for changing the worlds of the people in them, telling the tales of their own valuable lives.

3 pings

[…] and what a great book! The two novels that just missed the cut were Perhaps the Stars, and The Witness for the Dead, which is the second book in the Goblin Emperor world. I’d have traded those two for Project […]

[…] Grief of Stones begins with the execution of a murderer uncovered by Thara Celehar in The Witness for the Dead. His friend Anora is trying to talk him out of attending, saying Celehar is punishing himself, and […]

[…] other disputes. Their abilities also enable them to do things like still undead ghouls. In both The Witness for the Dead and The Grief of Stones Celehar has put his supernatural skills in the service of the people around […]