In 1808 the United States made the importation of slaves illegal, but illegitimate trade in humans continued until the eve of the Civil War. Supply and demand persisted on both sides of the Atlantic. “Habituated to the lucrative enterprise of trafficking and encouraged by the relative ease with which they could find buyers for their captives, Africans opposed to ending the traffic persisted in the enterprise.” (xviii) Enslaving people had a traditional role in some societies, capturing slaves brought political dominance, and selling them onward brought wealth, which in turn bought more power.

“King Ghezo of Dahomey renounced his 1852 treaty to abolish the traffic and by 1857 had resumed his wars and raids. Reports of his activities had reached the newspapers of Mobile, Alabama. A November 9, 1858, article … caught the attention of Timothy Meaher, a ‘slaveholder’ who, like many proslavery Americans, wanted to maintain the trans-Atlantic traffic. In defiance of constitutional law, Meaher decided to import Africans illegally into the country and enslave them. In conspiracy with Meaher, William Foster, who built the Clotilda, outfitted the ship for transport of the ‘contraband cargo.’ In July 1860, he navigated to the Bight of Benin. After six weeks of surviving storms and avoiding being overtaken by ships patrolling the waters, Foster anchored the Clotilda at the port of Ouidah.” (xix)

A young man named Kossola was among the thousands being held in the slave pens in Ouidah. He had been captured in a raid on his home village and brought over land to be sold overseas. He survived the passage on the Clotilda, the last known transport of slaves to the United States. He was enslaved on a farm in Alabama until 1865 when Union troops brought news of his freedom. Thereafter, he lived in a settlement of former slaves known as Africatown (later, Plateau) working as a farmer and a laborer until an accident made him incapable of heavy labor. The community appointed him sexton of the church. That was his occupation when Zora Neale Hurston, then a student of anthropology (she worked with Frank Boas, who also taught Ursula K. Le Guin‘s father), visited Kossola in 1927 and wrote down his history and stories.

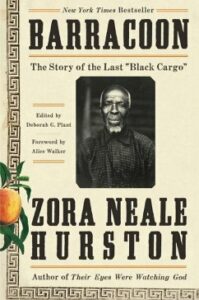

Hurston published an article or two based on her conversations with Kossola (often known by his American name of Cudjo Lewis), but she did not ever manage to find a publisher for her longer manuscript that told Kossola’s full story. Part of the problem was that she was attempting to place it during the depths of the Great Depression, when every part of the publishing business was more difficult. Another aspect is that she wrote his speech in dialect. It captures the style and rhythms of his speech, bringing him to life for readers, but writing African-American speech in phonetic dialect was and is a fraught authorial choice. Barracoon remained unpublished in Hurston’s lifetime.

The book that was published in 2018 as Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” contains Hurston’s main narrative of Kossola’s live, which itself has a preface and an introduction plus an appendix of six bits of background: the rules of a children’s game and five stories he told Hurston. In addition, Barracoon features a foreword by Alice Walker, an introduction, an editor’s note, an afterword by editor Deborah G. Plant, acknowledgments, a list of the founders of Africatown, a glossary, notes, bibliography, and a reprint of “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” by Alice Walker that was first published in Ms. in March 1975. The ancillary material comprises nearly half the book, giving considerable context on Hurston, Kossola and their entwined stories.

Kossola’s story itself is gripping. He begins with life in his village, his father and his grandfathers, the traditions of the people around him and the way he was brought up. Hurston captures the spirit of her visits, so that Barracoon reads very much like people just talking, a young person respectfully listening to an old man who is sometimes moody but grateful, sometimes tearfully grateful, that the story of his life will not be lost. Though more than half a century had passed since his enslavement, Kossola’s memory had not faded. Here he describes what happens when the captives arrived in Alabama:

First, dey ‘vide us wid some clothes, den dey keer [carry] us up de Alabama River and hide us in de swamp. But de mosquitoes dey so bad dey ’bout to eat us up, so dey took us up to Cap’n Burns Meaher’s place and ‘vide us up.

Capn’n Tim Meaher, he tookee thirty-two of us. Cap’n Burns Meaher he tookee ten couples. Some dey sell up de river in de Bogue Chitto. Cap’n Bill Foster he tookee de eight couples and Cap’n Jim Meaher he gittee de rest.

We were very sorry to be parted from one ‘nother. We cry for home. We took away from our people. We seventy days cross de water from de Affica soil, and now dey part us from one ‘nother. Derefor we cry. (p. 56)

Near the end of Barracoon, Hurston assesses her time with him:

I had spent two months with Kossola, who is called Cudjo, trying to find the answers to my questions. Some days we ate great quantities of clingsome peaches and talked. Sometimes we ate watermelon and talked. Once it was a huge mess of steamed crabs. Sometimes we just ate. Sometimes we just talked. At other times neither was possible, he just chased me away. He wanted to work in his garden or fix his fences. He couldn’t be bothered. The present was too urgent to let the past intrude. But on the whole, he was glad to see me, and we became warm friends. (p. 93)

Kossola’s lifetime overlapped with the lives of my children’s German grandparents, who are slightly older than my own parents. Kossola died in 1935, eight years after Hurston’s visits that form the core of Barracoon, and he was long thought to be the last survivor of the Clotilda. Research in the twenty-first century has found two others who outlived him. Radoshi was about age eight at the time of the transport and was one of those Kossola said were sold up to Bogue Chitto; she lived until 1935. Matilda McCrear, who was about age two when she and her mother and three sisters were transported to the United States; she lived until 1940. I started school in Mobile, Alabama, about a dozen miles from where Kossola lived his American life. My kindergarten class was the first year that public kindergartens were integrated in Mobile.

Dahomey was, in its way, just around the corner.