In 1999, Gail Simone made a list “when it occurred to [her] that it’s not healthy to be a female character in comics. … These are superheroines who have been either depowered, raped, or cut up and stuck in the refrigerator. Some have been revived, even improved — although the question remains as to why they were thrown in the wood chipper in the first place.” Once you start to notice how often female characters exist merely to motivate male characters you can’t stop seeing it.

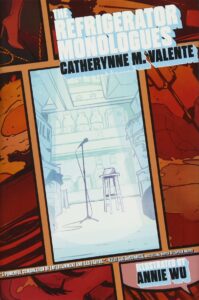

In The Refrigerator Monologues, Catherynne M. Valente gives voice to six such women. It’s a ferocious deconstruction of comic-book tales, undertaken by a true fan who wants them to be better, who knows they could be better, and who is utterly indignant about the laziness that keeps them from being what they could be. And in an age when comic-derived stories make billions at the box office and spawn many more tales on smaller screens, improving the source matter is hardly a trivial notion. Valente explains in her acknowledgments:

From the bottom of my heart, I would like to thank the pantheon of comics writers, artists, and creators—great and small—who built the grand superhero universe in which we have all been swimming in over the last century. None of my girls and none of my heroes could possibly exist without them, and even when I get my anger on, I have nothing but respect and honor for the monumental feat of deliberate mythology that they have, and continue to, accomplish. …

More specifically, the deepest bow and greatest thanks must go to Gail Simone, who first noticed, named, and collated evidence for the phenomenon of Women in Refrigerators and brought it to the attention of the culture at large and who has fought the good fight for decades. … On the other side of the coin, thank you to Even Ensler, whose The Vagina Monologues detonated the theatrical scene when I was coming-of-age as a young feminist-actress type of thing. Both in title and structure The Vagina Monologues gave me a sturdy framework on which to hang my frustration with the roles of women in superhero stories. (pp. 149–50)

Paige Embry was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt, about that. It’s the first thing she says, “I’m dead. The deadest girl in Deadtown.” And where she fits in the overall picture, “Dying was the biggest thing that ever happened to me. I’m famous for it. If you know the name Paige Embry, you know that Paige Embry died. She died at night. She died stupidly. She died for no reason.” (p. 1) Well, she died to give her boyfriend, Kid Mercury née Tom Thatcher, someone to grieve. “And the thing about me is, I’m not coming back. Lots of people do, you know. Deadtown has pretty shitty border control. If you know someone on the outside, somebody who knows a guy, a priest or a wizard or a screenwriter or a guy whose superpower shtick gets really dark sometimes or a scientist with a totally neat revivification ray who just can’t seem to get federal funding, you can go home again.” (p. 2) But not Paige.

She’s the first of six women in the book who tell their stories, and she narrates the bridges between the monologues. They’re set up as a get-together of the Hell Hath Club, an informal group of women who have shared similar fates, sacrificed for someone else’s narrative. The characters and stories reflect famous comics narratives, although I am not well versed enough to identify all of them. Paige Embry echoes Gwen Stacy, Peter Parker’s first girlfriend, who is murdered by the Green Goblin. The second monologue, “The Heat Death of Julia Ash,” is a reworking of the Phoenix/Dark Phoenix saga that first appeared in X-Men comics in 1980 and was used several times since in X-Men movies and television shows. “The Ballad of Blue Bayou” gives a different perspective on the origin of Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner, while the last monologue in the book, “Happy Birthday, Samantha Dane” riffs on the story with a girl in a refrigerator that originally inspired Gail Simone’s list. Full circle.

The monologues are not just action-packed exposés of how things really happened in the superheroes’ stories, they’re often funny, as when Blue Bayou dishes about life in the sunken city. “You think of an underwater city and your brain spins up all these postcards of clean turquoise water and whitecaps and frolicking orcas off a Lisa Frank notebook. But the ocean isn’t like that. It’s full of salt and sewage and tanker oil and mud and dead dolphins and fish poop and about a billion and four jellyfish. We don’t live in Atlantis because it’s a pristine paradise. We live there because we’re weird, gross aliens and Brooklyn’s full.” (p. 75) Or, more bleakly, Daisy Green realizing what a tawdry cliché her life has become. “It’s the kind of thing some asshole in Ohio gets a National Book Award for writing while he screws his grad students and cries his way to tenure.” (p. 116) #NotAllGuysInOhio, obvsly.

Valente returns to these women what the writers took from them in the original stories: their centrality. They don’t have to be wonderful people, they don’t have to have noble stories or even terribly good ones, they don’t have to be smarter or much more self-aware than the men around them (though that’s often a low bar to clear). In the Hell Hath Club, they get to tell their own stories. That’s more than enough.