It’s starting to get cold here in Maryland, so time for my thoughts to turn to hot soups and snuggling under the covers with a creepy tale or two! First up, an American classic that isn’t, perhaps, as overtly scary as its reputation has made it out to be, tho many literary people have certainly gone looking for a there that isn’t there. Or perhaps I have been merely been desensitized by years of reading thrillers: I imagine the subject matter back when it was written in the 1960s seemed far more transgressive of the “natural”. Still, that doesn’t excuse modern critics from parroting similar interpretations over half a century on.

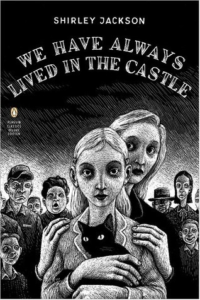

Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived In The Castle is an extremely straightforward story of the remnants of a traumatized family living in a small town that hates them, but its reputation has been built up in such a manner that I’m honestly baffled, having finally read it, when people suggest it should be treated as metaphor, as if the story itself needs to be metaphysically papered over in order to work. The edition I read included an afterword by Jonathan Lethem (and thank you to the editor for wisely sticking it at the end of the book instead of the front) which aimed to point out the obvious to, I assume, the oblivious. While I did appreciate the inclusion of certain of Ms Jackson’s biographical details that likely influenced the writing of the book, I was less enthused by Mr Lethem’s smug championing of her work as well as by his unnecessary (and IMO occasionally wrong) analysis of the text. Hence this rant.

Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived In The Castle is an extremely straightforward story of the remnants of a traumatized family living in a small town that hates them, but its reputation has been built up in such a manner that I’m honestly baffled, having finally read it, when people suggest it should be treated as metaphor, as if the story itself needs to be metaphysically papered over in order to work. The edition I read included an afterword by Jonathan Lethem (and thank you to the editor for wisely sticking it at the end of the book instead of the front) which aimed to point out the obvious to, I assume, the oblivious. While I did appreciate the inclusion of certain of Ms Jackson’s biographical details that likely influenced the writing of the book, I was less enthused by Mr Lethem’s smug championing of her work as well as by his unnecessary (and IMO occasionally wrong) analysis of the text. Hence this rant.

Anyhoo, WHALitC is narrated by Mary Katharine “Merricat” Blackwood, an 18 year-old seemingly frozen on the cusp of womanhood. She lives by a set of very strict rules handed down by her beloved, almost-a-decade older sister, Constance, with whom she lives in a beautiful house on the outskirts of town. Their mother had insisted that their father set up a wall all around their property, cutting off easy walking access from the village to the highway, because she didn’t like the villagers crossing so close to their front door. But their mother is dead now, as is their father and brother Thomas and Aunt Dorothy. Only their invalid Uncle Julian survived the deadly dinner that killed the rest of them, and for which Constance was charged with but eventually acquitted of murder.

As the book opens, Merricat is describing one of her twice-weekly walks to town for supplies. She hates the people there and it seems the loathing is mutual, tho it’s easy to read between the lines of her unreliable narrative. She’s happiest back home with her cat Jonas and with Constance, whose agoraphobia doesn’t stop her from running a functioning and warm, if quite small, household. With spring taking hold, Merricat resolves to be kinder to Uncle Julian, and constantly checks in on the many protective totems she’s placed around the grounds of the estate in an effort to keep out trespassers. She’s concerned however that Constance is starting to show signs of interest in leaving the grounds for the first time in years.

And then Cousin Charles appears. Loud and vital, he quickens something in Constance, who seems blind to his obvious flaws. So Merricat will have to take matters into her own hands, and not, as is glaringly obvious from the first few pages, for the first time either.

I came to this book after Cynthia’s scathing review of Paul Tremblay’s A Head Full Of Ghosts, and while the similarities there teeter between homage and a less sincere imitation, I do feel that WHALitC reminded me most, at least tonally and in its ending, of Marilynne Robinson’s harrowing Housekeeping. I don’t think Housekeeping was meant to be a horror novel — honestly, I don’t think WHALitC should be considered a horror novel either — but both books evoke a creepy sense of detachment from reality, a willing embrace of a self-destructive co-dependency that eschews “normal” society. WHALitC leans into that more tho, I feel, talking as well about sex and class in a masterclass of very pointedly discussing a subject while never addressing it directly. It’s a weird, sad, creepy book, a beautifully written Gothic mystery with, in the form of Uncle Julian’s ravings regarding Merricat, just enough supernatural influence to make it the kind of book people would recommend at Halloween. Personally, I felt it a cautionary tale for rich people: teach your kids how to get along with the poors or set them up for anguish and implosion, tho I don’t think that was Ms Jackson’s aim at all. More’s the pity, as this is one of the best examples of what inevitably happens to dynasties that consider themselves better than the hoi polloi. I wonder sometimes how the literary criticism of this book has been influenced by the critics’ own assumptions of class, whether aloofness or solidarity are their watchwords. In this neverending year of 2020, one would hope for a greater empathy, and not one primarily reserved for the murderous rich either.

We Have Always Lived In The Castle by Shirley Jackson was published September 21st, 1962 (complete coincidence that I originally published this review on its 58th anniversary!) and is available from all good booksellers, including

Want it now? For the Kindle version, click here.